“Go to Italy. It’s a peaceful country, nothing much ever happens there.”

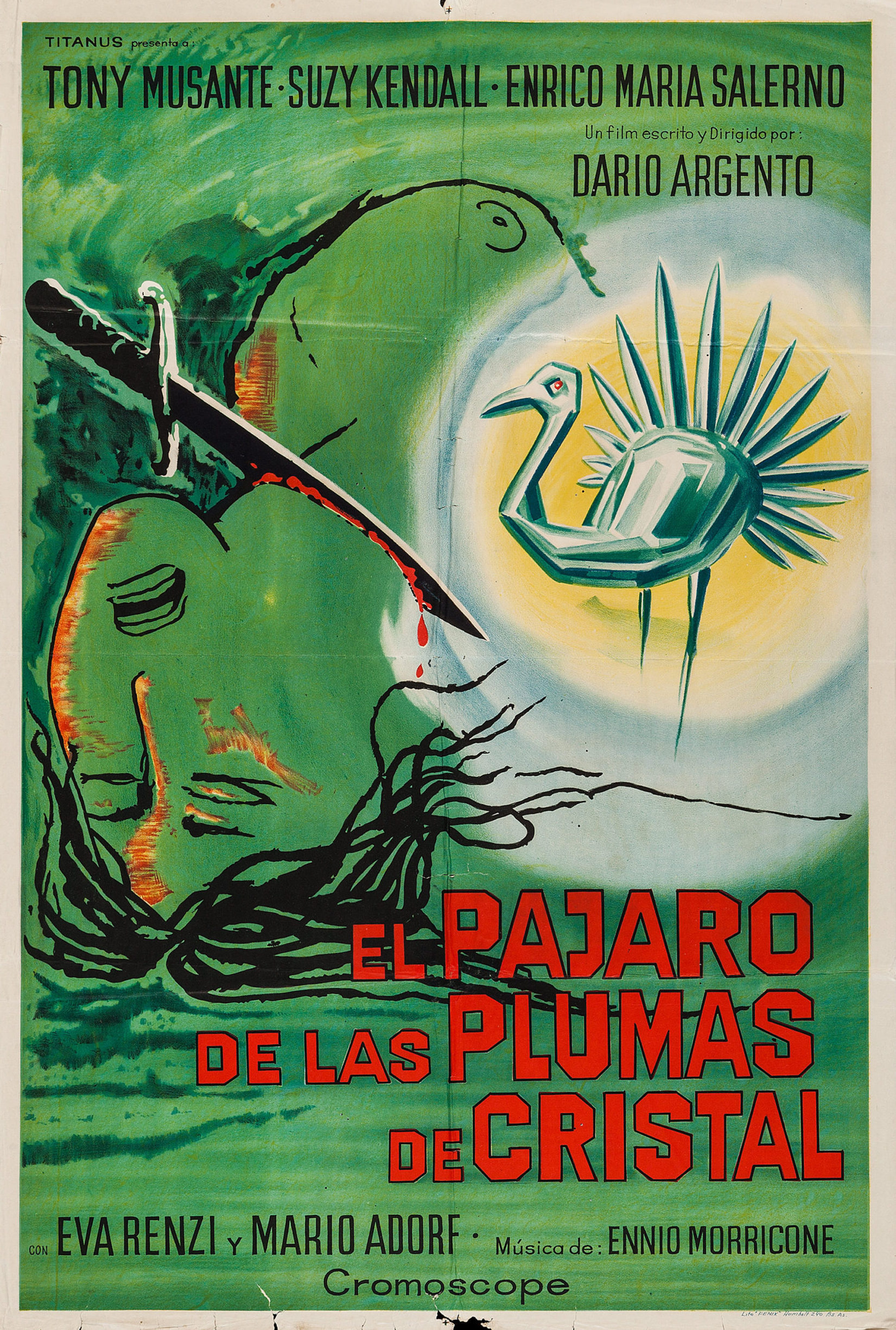

It’s always a joy to revisit a filmmaker’s early work and see a trademark style in its infancy. In The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, Dario Argento announces himself with a highly stylized thriller that showcases many of the tics and flourishes that would define his later masterworks. It reads like a rough draft of his recurring themes, motifs, and composition styles except less bloody and sexualized than what was to come (though blood and sex are still very much part of the film’s textual fabric). It’s evident even at this beginning stage that he is aiming to develop a fresh cinematic language, one that pulls equally from vernaculars of avant-garde and exploitation cinema. But while his knack for gorgeous set design, choreographed violence, and breathtaking cinematography are almost fully formed, he hasn’t yet learned to use spectacle to mask his weaknesses. Despite its rough edges, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage is an engrossing giallo chiller from an emerging voice that displays many of the traits that would in time define his body of work and confirm his intuitive style.

Argento boldly arrests the viewer in the film’s opening moments without any pretense. A mysterious figure wearing a black cloak, black hat, and black leather gloves, whose visage remains obscured by shadows, carefully taps away at a typewriter in a dimly lit room. We’re then transported to the streets of Rome, covertly watching and, as the occasional freeze frame informs us, photographing a young woman wandering about the city, in first-person POV. Back in the dark lair, the shadowy stalker shuffles through a series of developed photographs and selects a gleaming knife from a velvet-lined case full of sharpened cutlery. The knife is tucked beneath a slicker and the screen fades to black. Within a span of two minutes, we’ve been drawn in by voyeurism and narrative uncertainty.

In the film’s proper opening sequence, both of these themes are echoed in combination with two more Argento staples—the unreliable witness and the impotent male. Sam Dalmas (Tony Musante), an American writer looking to spark his creative energy in the romantic European city, is wandering alone in the dead of night when his eye is caught by a disturbance in a highbrow art gallery across the street. A dark figure is violently struggling with a red-haired woman on the building’s second floor. Sam rushes to the scene but finds himself trapped between the two glass doors of the foyer as the cloaked assailant slips out a back door and Monica (Eva Renzi) stumbles down to the ground floor and bleeds from a stab wound to her torso. Sam, already emasculated by the unshakeable writer’s block that prompted his vacation, finds himself a helpless captive, capable of watching but not participating in the lurid episode unfolding before his eyes. His reassurances are muffled by the glass while Monica screams silently from inside the gallery.

The police and paramedics finally arrive and rescue Monica—who has suffered only a flesh wound—and immediately turn their attention to their primary witness. Sam recounts the scene, but an elusive detail lingering on the periphery of his memory nags at him. His account is unsatisfactory to Inspector Morosini (Enrico Maria Salerno), who believes the assailant may be the same serial killer who’s committed a string of murders over the past months. The episode continues to haunt Sam, who is repeatedly drawn back into the memory in a trance state, turning it over and over in his mind’s eye searching for that slippery datum as he launches an informal investigation of his own. The pieces will eventually fall into place, but not before Sam’s barely avoided decapitation, another victim has been claimed, and his girlfriend Julia (Suzy Kendall) is nearly gutted in the couple’s apartment.

The general scenario, a few iconic images, and several prominent themes became part of Argento’s standard repertoire and he would revisit it a couple more times throughout his career—most notably in his masterful Deep Red. He mostly succeeds in this first go around but finds himself constrained by a procedural narrative derived from Fredric Brown’s The Screaming Mimi. As Sam follows an increasingly bizarre trail of breadcrumbs that sees him interviewing a pimp, borrowing a print from an art dealer, tracking down an outsider artist with an appetite for cats, and locating a rare Siberian bird, the straightforward nature of his pursuit and the abundance of red herrings occasionally threatens to dampen the momentum that Argento so easily musters with his technical mastery. Even so, he maintains an effective sense of paranoid tension as each carefully arranged shadow seems to obscure a new menace. And once the mystery resolves with at least two effective fakeouts in quick succession, it manages to leave us flabbergasted. That last clue had been staring us, and Sam, in the face the entire time. (Although I’m suspicious if the crucial detail is as apparent as we are led to believe during the first few replays of the scene in question.)

In any case, the film’s potency comes not from its derivative story but from the powerful themes and distinctive presentation. While in various instances he’s clearly indebted to Hitchcock and Bava, Argento’s individual style is clearly present in his visual compositions. He painstakingly created a shot list of the entire film and fought bitterly to materialize the vision in his mind even when his producer tried to fire him. He even went so far as to intentionally ruin an expensive camera in order to capture a stunning first-person view as a character falls to their death from a great height (a trick Kubrick stole for A Clockwork Orange).

Argento would lean into his lustrous cinematographic style even more in subsequent efforts but The Bird with the Crystal Plumage is by no means the work of an amateur. Collaborating with Vittorio Storaro, Argento captures a series of beautifully composed shots that make use of shadow and color, clutter and negative space, to play with the viewer’s attention and instill every scene with a sense of vague disorientation, as if we’re being led to the cusp of a revelation that isn’t necessarily going to come. And I can’t fail to mention the partially-improvised soundwork from the legendary Ennio Morricone which is by turns buoyant and sinister. The polish is stunning for a debut effort.

While Mario Bava had essentially launched the giallo era in the early 1960s with The Girl Who Knew Too Much and Blood and Black Lace, it was The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, which builds on those early works, and the ensuing early career of Argento that sharpened the genre into its popular form and provided several classic entries into the canon. Already a technical savant, we can glimpse in this early work so much of what would come to define the auteur, from POV shots, black gloves, and chiaroscuro lighting to psychosexual trauma and amateur detective work. A quintessential giallo that tastefully touches on most of the genre’s tropes and provides an archetype for the genre’s golden age.