“Death has come to your little town, Sheriff.”

Halloween made something like $70M against its $300k budget (half of which went to a Panaglide camera setup), ensuring that every little old studio in existence would try to replicate its success. The problem with this little cottage industry of suburban horror movies, which came to be known as “slasher flicks,” is that very few of them were helmed by a filmmaker of John Carpenter’s caliber.1 In Carpenter’s capable hands, a simplistic keyboard riff and a subjective camera can render a man standing still in broad daylight in public absolutely petrifying. Of course, that man is Michael Myers, disguised by an infamously hideous and inhuman William Shatner mask, but that’s besides the point and anyway only supports the idea that the man’s instincts were unerring circa the late 1970s.

The film’s scenario is established in an impeccable one shot prologue set in 1963 (yes, yes, it’s actually three shots stitched together, but you’d never know that unless you liked the film well enough to study it or you took in a behind-the-scenes documentary) wherein a first-person camera depicts the murder of Judith Myers (Sandy Johnson). There isn’t a cut until the murderer stumbles out onto the front lawn, bloody knife in hand, at which point it is revealed that Judy was killed by her six year old brother Michael (Will Sandin). Fifteen years later, Michael (Nick Castle) breaks out of the sanitarium and returns to his hometown where he stalks and terrorizes a group of babysitting teenagers (Jamie Lee Curtis, P. J. Soles, Nancy Kyes), ultimately claiming three new victims.

Clearly, there’s no getting around the fact that Halloween fits the definition of a slasher film to a T and thus had a hand in establishing the subgenre. But even so, it’s also certain that the precise manipulations of Carpenter’s nearly bloodless film are an entirely different (and more successful) scare tactic than the grisly butchery of its imitators. Indeed, one need look no further than Halloween II and Halloween III: Season of the Witch to find films that trade in the unsettling tension of the original for a higher body count and nastier deaths, and suffer for it.

As Tom Allen points out in his insightful Village Voice essay (which turned the critical tide on the film shortly after its release), Carpenter basically attempts to recreate the unyielding suspense from the shower scene in Psycho and then stretch it to feature length. For ninety minutes, the viewer is held in a dreadful state of anticipation as every darkened corner and fluttering curtain threatens to be hiding the diabolical force of nature that’s terrorizing our protagonists. The film does offer brief reprieves that flesh out the wholesome community of Haddonfield, IL via banal banter of highschoolers, young trick-or-treaters, and local police officers; but even these expositional scenes are laced with suspense from the chilling score and peripheral appearances of the fiend, effectively underscoring the notion that evil has pervasively infiltrated the once-safe suburb.

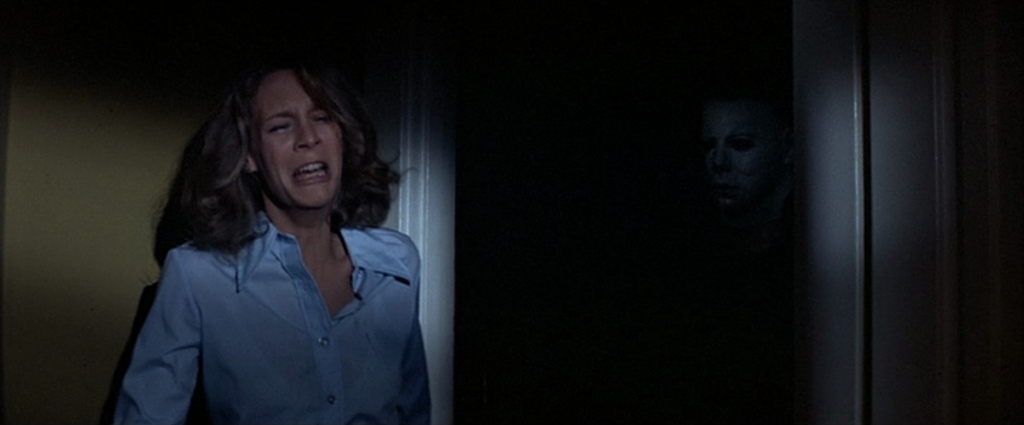

That tantalizing sense of unease is the film’s primary achievement and it is edifying to dissect Carpenter’s methods in realizing it. As noted, Carpenter is in complete control of his camera throughout the film, and his voyeuristic framing has become a staple of the genre, but he does a lot of other noteworthy things that elevate the trepidation. Shooting in California in springtime, which, of course, looks nothing like Illinois in the fall,2 Carpenter had DP Dean Cunley push the daylight scenes toward orange and the night scenes toward blue, creating an uncanny visual palette that seldom feels “real.” Slightly detached from reality, then, verging into the realm of nightmare and fable, he conceals and obscures the adversary with distance and shadows until he is ready to bring him in close proximity to his victims. As the film progresses and the tension builds and then holds at an impossible pitch, he gradually confines his cast by moving from outdoors, to dimly lit interiors, until Laurie (Curtis) is cowering in a closet and defending herself with a clotheshanger. Even then, Michael’s mask conceals his face, allowing the single instance where his features are briefly exposed to provide a momentary shock. Several shots—a “dead” Michael sitting up in the background as Laurie recovers from her struggle, Michael materializing out of the shadows as Cunley slowly amplifies the light source—literally take your breath away the first time you see them.

Though sequels would delve into the nature of Michael’s origins and his connection to Laurie Strode, Halloween presents a villain without any clear motive; an implacable, voiceless, ultimately unknowable killer, who dispassionately observes a corpse he’s pinned to the wall with a butcher knife one moment, and the next, throws a sheet over his head as a chintzy ghost costume and wears the dead man’s glasses in order to confuse the next victim. He’s clearly a lethal menace, but we don’t know what drives him, meaning that every glimpse of his likeness or threat of his presence is awash with a sense of peril, as his expressionless mask and lack of motive allow us to project our most primal anxieties onto him. And virtually the whole film posits a Schrödinger’s cat situation—he’s hiding in the closet, or just off to the side of the camera, or lurking in the shadows, but we can never be sure. In effect, he’s anywhere and everywhere at once, as emphasized by the closing montage (set to Michael’s heavy breathing) that shows places he’s been, places he may be, places now tainted with evil that we are helpless to stop him from invading. Note that this sequence “should” release the tension, but it only makes it worse; you walk away without a sense of closure because evil remains at large.

Likewise, the tacked-on nature of Dr. Sam Loomis’ (Donald Pleasence) futile pursuit of his escaped patient undergirds that sense of helplessness. Carpenter and co-writer Debra Hill include conversations amongst the girls about dates and sex and cheerleading to establish a rapport between the audience and the characters, but only imply discussions between Loomis and the sheriff (Charles Cyphers) because to include them would shift our attention too far away from the central tension. Indeed, Loomis spends much of the film impotently waiting and only connects with the main story in the final scenes, wherein his lack of surprise at Michael’s ability to absorb several pistol rounds and walk away elevates the villain into the realm of mythology. Loomis’s purple prose, which Pleasence indispensably delivers with vigor, suggests that the manchild is evil incarnate, and as such, isn’t killing teenage girls because they have wronged him or because he is insane or because of some sexual perversion, but simply because his nature compels him to.

If little of what Carpenter’s doing here is entirely original but rather an inspired assemblage of existing idioms, he’s certainly doing it with a lot of chutzpah. What ultimately draws viewers, myself most definitely included, back to Halloween again and again is its shiftiness, its inscrutability. Conceived as “The Shape,” Michael Myers is an elusive preternatural force that doesn’t belong to the world we know even though he inhabits the flesh of man. His existence cannot be explained satisfactorily—he cannot be, and yet he is—and so his inhuman visage continues to haunt us.

1. It remains unclear to me why Halloween is elevated as the father of the slasher flick, when several earlier forerunners probably deserve the tag more, e.g. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre or Black Christmas or any number of gialli. Even though Carpenter was initially rebuffed by students at his alma mater at an early screening who considered his film too sordid for good taste, one wonders if critical consensus hasn’t alighted upon Halloween because it is exceedingly well crafted in addition to being massively commercially successful.

2. For all the deliberateness of Carpenter’s filmmaking, it’s amazing to watch an interview where he acknowledges that a few scenes feature palm trees and is like, “eh, what the hell.” It’s the same nonchalant tact he takes when he describes how they decided to use a William Shatner mask or how he just came up with the 5/4 time musical motif like it was nothing.