“Do you even know why you’re supposed to kill me? Look at us. Look at what they make you give.”

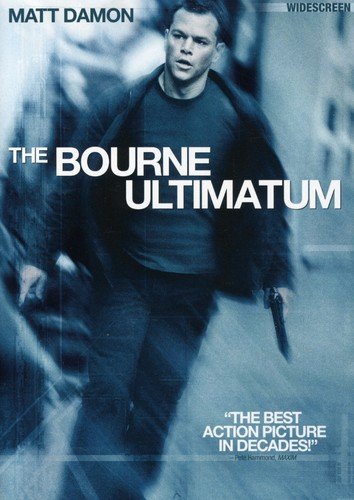

Are audiences and critics so starved for solid blockbuster action movies—so deprived of sophisticated spectacle—that they’ll fawn over an efficiently made, middle-of-the-road spy thriller with nary a hint of narrative depth or genuine emotion? That the artless assembly of intense action sequences feels like a breath of fresh air? The sad answer is yes, though I’ll digress before I run the risk of critiquing tastes and trends instead of the film in question. Like the two entries that preceded it in the trilogy, The Bourne Ultimatum is so far removed from the book from which it takes its name that it’s only honest to assess it as an entirely separate entity with a brand name slapped on it (a practice that Eon has repeatedly done this with Ian Fleming’s work; I guess it comes with the territory). Leaving Ludlum in the rearview, writer Tony Gilroy and director Paul Greengrass lean into the visceral style of action that proved so divisive in the second film, focusing in on shaky cam violence at the expense of basically everything else. I’ll admit the action is a cut above the norm (although I’m personally unimpressed with the style itself) but there’s a distinct lack of big, dumb action movie charisma and/or a weighty story. Obviously the latter is what one would expect given the source material, but the inclusion of either of those elements could have elevated The Bourne Ultimatum in a significant way. Without them, all we’re left with is Greengrass’ signature choppy action capturing some impressive stunts and Matt Damon prancing around as a kind-hearted macho man assassin. It’s mildly fun while you’re watching it and then it’s faded from memory five minutes later.

A whirlwind of vague ideas and murky contrivances are presented to us for the sole purpose of putting Bourne in tight spots and letting him whoop up on the bad guys under pressure. The Bourne Ultimatum begins prior to the ending of The Bourne Supremacy, with Bourne frantically outmaneuvering Moscow policemen as he bleeds from a gunshot wound. His uncanny instincts, combat skills, and evasive techniques prove too much for his pursuers, and six weeks later he’s still not been pinned down. Bourne’s solitary objective is to learn about his own past, a personal history that’s buried in a classified file under several layers of red tape from some government agency or another. He knows about Treadstone and that he used to work for them, but little else. He tracks down an investigative journalist (Paddy Considine) who has written a newspaper article about a program called Blackbriar, a reconfiguration of the Treadstone operation, citing an unnamed source within the organization. Blackbriar itself, headed by Noah Vosen (David Strathairn), catches wind of the meeting through cell phone surveillance. However, they misread the situation and conclude that Bourne is the journalist’s inside source. And then we’re off to the races, globe hopping from Moscow to Paris to London to Madrid to Tangier to New York.

The main storyline feels entirely too familiar, even excepting the weird repeat of the second movie’s final scene. Some of the players have changed—Scott Glenn takes on a black ops supervisory role, Édgar Ramírez is the agency’s hitman, Daniel Brühl is the regular person who cannot comprehend the world of Jason Bourne—but they’re filling well-worn roles. Pamela Landy (Joan Allen) and Nicky Parsons (Julia Stiles), also Treadstone alumni, change allegiances and actively help Bourne, which doesn’t make sense within the story but fits simply because they’re the only two characters who have been in previous films and thus seem like old friends. The unit that had previously hunted Bourne to cover up internal fraud has been replaced by an anti-terrorism task force, but the “kill Jason Bourne on sight” modus operandi has not changed and for all we care they’re essentially the same. They bicker inside of office buildings and fall for all of Bourne’s tricks and get upset when they cannot covertly monitor a call made on a tracfone that had been activated five seconds ago. Bourne and Blackbriar simultaneously track an evasive CIA agent (the journalist’s actual source) which ties Bourne into an effort to expose corrupt government agencies. He must navigate this situation without adequate memory, following a trail of breadcrumbs that we come across as he does which allows the screenwriters plenty of wiggle room for retcons and spontaneous inventions of backstory.

Dr. Albert Hirsch (Albert Finney), the psychologist who oversaw Treadstone’s intense behavioral modification program, makes an appearance as Bourne confronts his past; at first via hazy flashbacks and then face to face. This should have been a culmination of the entire trilogy, the grand emotional crescendo it was building toward, but instead it feels like an afterthought that has little bearing on the rest of the film. I mean, was Hirsch even mentioned prior to Ultimatum? But then again, neither were most of these characters who suddenly appear out of nowhere and are hellbent on killing Jason Bourne.

And that’s where I feel that the entire trilogy is a letdown. I don’t care that they’ve discarded Ludlum’s lengthy novels in favor of using his popular brand to gain an audience. But they’ve failed to replace his stories with something meritorious. Instead, they’ve simply repeated the same tricks, often verbatim, sometimes with a little bit more intensity—but always with the drunkenly bobbing frame, like a handheld camera was strapped to a manic chihuahua. The shots are sliced and diced to such minuscule lengths that it’s impossible to truly appreciate the elbow grease that went into producing the sequences. Occasionally the editing is so rapid and the camera so unsteady that even if one isn’t averting their eyes to avoid nausea they stand no chance of comprehending what is physically taking place on screen.

In any case, none of the things that make the Bourne films subpar distract from their intended purpose, which is to provide a gritty alternative to James Bond. Except you can’t call it “realistic” because Bourne takes more abuse than Bond and is rarely hurt for more than a few minutes. And yet Greengrass’ docudrama aesthetic, which he employs much better when making films about true events, begs to be taken seriously.