“It’s a work of pure unadulterated ego.”

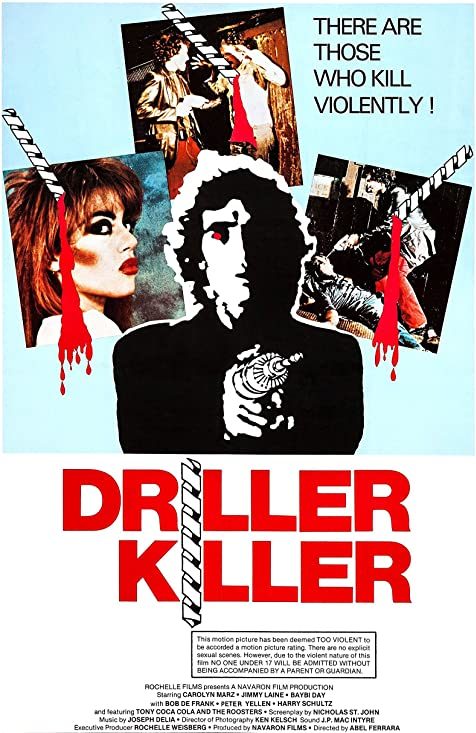

In 1982, Vipco, a UK based distributor of obscure and cult films, took out a series of full-page ads for Abel Ferrara’s debut feature, The Driller Killer. The ads depicted a close up of a man screaming in agony as blood dripped down over his eye and splattered from a drill bit viciously chewing through his forehead. They were just trying to provocatively drive sales but, unwittingly, kicked off a moral controversy over “video nasties” that led to the Video Recordings Act 1984. In effect, this made the sale of any unclassified films illegal and required “obscene” ones to be edited down for commercial release or else be banned from distribution. The standards were eventually relaxed, but I find it amusing that such an overblown kerfuffle was caused by a single image advertising a movie that is fairly tame—scuzzy and implicative, sure, but it’s really just a psychological horror film with brief bursts of cheap violence.

Moving on from the softcore pornography of his earliest days, The Driller Killer finds Ferrara (credited as Jimmy Laine) starring as Reno Miller, a starving artist type who can’t afford to pay rent on the squalid NYC studio apartment he shares with sometimes-lovers Carol (Carolyn Marz) and Pamela (Baybi Day), whom he treats like garbage. As his bills pile up and his roommates continue to while away their lives on drugs, pizza, and television, Reno focuses his effort on a potential masterpiece—a large painting of a blood-streaked buffalo that he hopes will bring in a sizable sum from a local gallery. But the pressures and distractions continue to mount. As if money troubles and violence in the news weren’t sufficient stressors, a sleazy No Wave band called the Roosters—fronted by a weirdo named Tony Coca-Cola (D.A. Metrov)—move into an adjacent apartment and begin practicing their incoherent squabble at all hours of the day, wrecking Reno’s sleep habits and making him susceptible to his worst impulses.

As he descends into a dangerous headspace from all of the sludge entering his brain, his murderous visions are brought into intense focus when he sees a commercial for a power belt that grants its wearer portable electricity. After pulverizing a skinned rabbit (bizarrely gifted to Reno by his landlord when he complained of the Roosters’ unceasing plonking), he takes to the streets with his drill and his new battery belt and becomes a vagrant-slaughtering maniac.

What’s funny is that The Driller Killer isn’t really all that violent. It takes half its runtime to get to the first kill, and then runs through variations of the same scenario: Reno tries to pull himself together, something upsets him, and then he blows off some steam by slaying another homeless person. Very few of these deaths are gory at all. The body count eventually tallies up into double digits, but from my recollection only two of them show blood, including the one depicted on the controversial advertisement. But in each case, the carnage is charmingly low budget. Even when the drill descends into the victim’s forehead it is obvious that the bit is not penetrating. The rabbit pulverization is much nastier than any human death in the film.

Ferrara’s vision of NYC as a grimy hellscape conveys Reno’s turn to madness with a primal immediacy. It’s artificial through and through with bursts of synthesizer and dream visions, but balanced by the raw energy of Reno’s back alley slinking/splattering and documentary-esque footage of paper bag drunks and sundry derelicts. Of primary interest is Ferrara’s self-casting—no doubt done out of necessity to see his work brought to fruition—that serves to align the filmmaker with his character and provides an excellent commentary on the world of art. Like Reno Miller, Abel Ferrara has spent his entire career mixing highbrow with lowbrow, art with trash, creativity with exploitative sleaze, arthouse with grindhouse.

As clearly as we can spot Ferrara’s obsessions here in nascent form, it’s not the case that he burst out of the starting blocks fully formed. The Driller Killer is amateur and stilted in many ways, from obvious and pointless symbolism to painful acting to misplaced confidence in the presentation. Consider the film’s opening, which promises Scorsese-esque moral confusion with its crucifix bathed in red light and its wizened old parishioner (possibly Reno’s estranged father) mysteriously grasping Reno’s hand—there’s no attempt at all to follow up on this as the film moves on. Consider also that Ferrara, who has wisely refrained from acting in his subsequent films (though he makes a small appearance in Ms .45), is perhaps the most distinguished member of his cast, the rest of whom mumble through their lines with the exuberance of sloths.

Ferrara occasionally draws some coherent musings out of the crude chaos he has whipped up, but more or less finds himself roaming his little corner of the city, documenting the incessant buzz of nomadic ramblings or tuneless electric guitars, and then taking a drill to the source of the noise. Perhaps most fascinating from a historical perspective is Ferrera’s documentation of the gritty and grimy punk scene of late 1970s NYC. There’s nothing particularly insightful offered by the director, who, as Reno, takes in a show at Max’s Kansas City, his pathetic existence contrasting with the enthusiasm of the punks and freaks enjoying the concert. In fact, if we take his character to be somewhat representative of himself, he has a startling disdain for those who enjoy the simple pleasures of crude punk, envisioning the legendary venue as an underground abode for misfits and delinquents. But as he momentarily allows his film to be overtaken by slinky basslines and crunchy riffs, it’s thrilling to look back at a venue that once hosted the likes of Iggy Pop, Bowie, T. Rex, Tom Waits, Bruce Springsteen, etc. and in its second iteration fostered the rise of punk rock in the hands of the New York Dolls, Patti Smith, and the Ramones.

While it may be unavoidable to take Ferrara’s self-casting and read The Driller Killer as semi-autobiographical (semi- because, as far as I know, Ferrara has never actually killed anyone, with a drill or otherwise), doing so seems entirely appropriate. The director had embarked on his journey as a filmmaker with ambition but found himself out of work shortly after leaving SUNY, forced into the porn business if he wanted to exercise his skills. In this light, it’s hard not to see The Driller Killer as a rambling, thinking-out-loud diatribe, to see Reno as an avatar for Ferrara’s frustrated desperation.