“For every shadow, no matter how deep, is threatened by morning light.”

Darren Aronofsky’s The Fountain reminds me of the ambitious flops of the late New Hollywood era. Most of those—at least the ones I’m thinking of—ran way over budget with elaborate set design and scenes of grand spectacle. In some instances, studio heads let their emotions overrule their understanding of the sunk cost fallacy and kept throwing money at auteurs with lofty aspirations. In the best of these cases the movies turned out great, even if we had to wait several decades to see them in all their non-studio-butchered glory (ahem, Heaven’s Gate). Unfortunately for Aronofsky, fresh off the one-two punch of Pi and Requiem for a Dream to begin his career, the descendants of the brothers Warner were not so trusting with their fortunes.

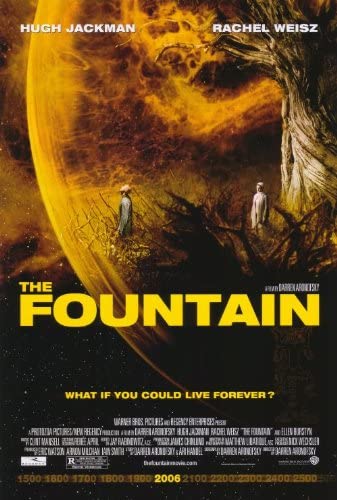

Pre-production for The Fountain began in 2001 (five years before the film would finally see theatrical release). Tens of millions were spent sending a crew to Central America to consult with Mayan experts and explore ancient ruins in Mexico and Guatemala (some may recognize Tikal as a fictional moon called Yavin 4) and to build a replica Mayan temple in Australia. All that got thrown by the wayside when megastar Brad Pitt dropped out of the project and headed for greener pastures (Troy). The whole thing was shut down for a time, during which the director struggled to find passion for new ideas, eventually working up the courage to slice and dice his own screenplay into a “no budget” version. After numerous rewrites, negotiations, recasts, etc. Aronofsky soldiered through on half the initial budget with his then-girlfriend Rachel Weisz starring alongside the not-quite-yet-a-household-name Hugh Jackman.

I cannot be convinced that The Fountain was initially conceived as a 1.5 hour film. There’re simply too many ideas and motifs and narrative threads flung scattershot at the viewer. Not to mention the burgeoning auteur’s flair employed for its own sake. It would have been served well by some additional breathing room. There’s a triptych of distinct yet interrelated narratives drastically separated by time and space. None of them are complicated but the means by which they’re stitched together is where I think the film becomes incomprehensible for many people—including the financially-driven execs who were looking at images of levitating monks, Mayan tribesmen, and Spanish conquistadors on storyboards.

The central story concerns Tommy (Jackman), a research scientist who discovers a Guatemalan tree that may have healing properties. His time is divided between frenetic lab trials on monkeys with brain tumors and caring for his wife, who is gradually succumbing to cancer. He remains on the brink throughout as he believes the research may lead to a cure for Izzi (Weisz) but if not, each minute he spends in the lab deprives them of a moment together. Izzi, meanwhile, has struggled to come to terms with her impending death but has found some comfort in the Mayan conception of the afterlife. One night Tommy finds her on their roof with a telescope, marveling at a golden nebula she calls Xibalba—she dreams, as she claims the Mayans did, that their souls will meet there in the afterlife when the star goes supernova.

She has found additional solace by using her disease as an impetus for writing—death giving birth to life, as she says. She presents her husband an incomplete handwritten work titled “The Fountain” and requests that he finish it. Engrossed in its pages, Tommy envisions himself as Tomás Verde, a conquistador commissioned by Queen Isabella to seek out the fountain of youth in the Mayan jungle in hopes of preserving her reign. While his queen loses her kingdom to the Holy Inquisition, Tomás faces off with a Mayan high priest at a sacred temple.

The third story arc—and this is the cause of the bulk of the head scratching, methinks—sees a future version of Tom, bald and garbed monklike, floating through space in a spherical terrarium. He levitates and meditates and mentally reaches through time and eats bark from a giant dying sweetgum tree that was presumably planted atop Izzi’s grave and somehow contains her essence. Determining who exactly this Tom is proves perplexing. Is this Tom Creo the researcher dreaming of his wife’s idea of the proximate afterlife? Is this his conclusion to her book? Or is this a man who discovered the tree of life in South America and used his immortality and centuries of accumulated experience to shuttle himself and the new creation born of his wife’s death to the Mayan underworld?

These three stories are tossed together with match cuts, upside-down shots, thematic transitions, slightly different replays of scenes… pinning down a sequence of events would be tough. And I think attempting it would undercut the film’s limited magic anyway. It’s not meant to be pieced together like an elaborate equation and pop “entertainment” out on the other side of the equal sign. Rather, it’s a ruminative piece that considers a very non-mainstream idea—coming to terms with your own death.

That’s not a regular topic of conversation because us moderns are terrified of dying thanks to the constant bombardment of secular propaganda that ensures us there is no spirit, no life after death, that all we are is a small assemblage of chemical reactions in an endless ocean of them. But of course we don’t feel that way and so we can’t find any comfort in the “knowledge” that our lives are meaningless. If you conclude that the infinite (read: God) doesn’t exist, or that it is impersonal or mindless or whatever, then all you have to build your worldview on is yourself, the same self that you’re told is just randomly firing synapses housed in bone and skin. That road leads only to despair or willful delusion so it’s mostly ignored in favor of fairytale daydreams, superficial worries, impactful work, etc. Anything to avoid thinking about the eternal nature of the soul. So kudos to Aronofsky for earnestly exploring the idea in a semi-mainstream film and making people uncomfortable.

If I had to put a stake in the ground, I’d say the interstellar bubble is happening in Tommy’s mind. The tree dies just before it reaches Xibalba just as Izzi dies shortly before Tommy has found a cure for her disease. This catastrophe causes the doctor who couldn’t fathom death as positive in any way at all is able to find inspiration in his wife’s death to finish her novel. He continually struggles to do so because leaving the book unfinished implies that Izzi by proxy is somehow not yet finished either. When Tommy finally accepts the reality of death he is briefly absorbed into Izzi’s story (of which he is now the author) in a moment of epiphany. The levitating spacemonk in lotus posture substitutes for Tomás the conquistador in the latter’s moment of need. The Mayan priest who was about to slay him stays his hand, recognizing the beatific floating figure as the First Father, the Creator of the world in Mayan mythology. In this way, Tom as the author acts as the god of his/Izzi’s fictional world, indicating a comprehension of God’s active hand in his creation. Crucially, though, Tomás still dies, his independent pursuit of eternal life proven futile in the end.

As a Christian, I obviously can’t endorse the mixed up philosophies of The Fountain wholesale. It plays with ideas that are very interesting but it’s ultimately confused and that’s kind of the point—that accepting death is not easy, especially when you can see it coming for so long. Still though, the film has a very poetic outlook on the necessity of death for new life, and that’s a main theme of the New Testament. I can’t say for sure that Aronofsky was going for that, but his smattering of other biblical references hint at it (but again, it’s also got some Mayan mythology and other mystical flavorings from the East all mixed together).

While The Fountain has unsurprisingly become a cult film, it has many detractors. Complaints target the needless complexity, the treatment of simple ideas as profound, the budget-friendly CGI, and the lack of focus on the excellent central performances. The only one I can really buy is that some of the potential is squandered by stepping back from the characters. This is why I wish the initial screenplay would have gone into production because I have a hunch that it was a looser tale and would have benefitted from a more relaxed pace. While I agree that the ideas are simple—as in they aren’t hard to wrap the brain around—that doesn’t mean they’re unworthy of the earnest, feature-length treatment Aronofsky gives them. To suggest that we shouldn’t ruminate on the reality of death just betrays that you wish to avoid the topic altogether. Anyhow that’s just a dumb argument on its face because most films have simple themes. I find the offerings here to be quite emotive and greatly uplifted by the performances from Jackman and Weisz (and Ellen Burstyn as well).

Aronofsky may stumble in trying to bring all of his ideas together with a grand unified ending that kind of undercuts the messiness of grasping at eternity with a finite mind, but it’s an awfully compelling film rendered oddly small scale and short by the studio’s hesitance to give the man his budget. Though it was not critically or commercially successful, The Fountain deserves to be discussed. Obtusely constructed by design, the storylines and possible realities and fictions are deliberately blurred, presenting a kind of cinematic Rorschach test for the viewer. Love it or leave it, The Fountain will be bouncing around in your head for quite a while.