“I don’t care about the money. I’m pulling back the curtain. I want to meet the wizard.”

The early filmography of David Fincher is mostly remembered for his franchise-stymying Alien 3, the enduringly popular crime-thriller Se7en, and the bro-classic Fight Club. Nestled between the latter two is The Game, a psychological horror film that is uncomfortable to watch. It’s uncomfortable because Fincher intentionally violates the unspoken pact between director and audience regarding the conventional composition of a Hollywood movie. He subverts our expectations by running roughshod over the implicit agreement so many times that halfway through the film we are forced to relinquish any mental conjecture of how the film will conclude. This is a risky move by the director—one that results in an edge of your seat experience—but one that is taken too far, resulting in a confused denouement in which our protagonist experiences a catharsis that we don’t share with him. We are meant to do so, but, overwhelmed by the successive fakeouts, we are incapable. Nevertheless, it’s a bold, artfully made film that brilliantly fleshes out its themes of paranoia and, to a lesser extent, personal loss.

The first twenty minutes or so of The Game are a sensational display of efficient storytelling, bringing us up to speed on the past and present life of our protagonist and setting up the film’s central conflict. Nicholas van Orton, portrayed excellently by Michael Douglas, is a dead man walking. Insanely wealthy, but divorced and friendless, he spends his evenings alone, eating reheated meals and watching the news. On his 48th birthday, at the exact age his father was when Nicholas saw him commit suicide by jumping off the roof of their home—the house where Nicholas still lives—his ex-wife calls him to wish him well. He makes small talk for a moment before abruptly ending the call and returning to the endless drone of the television.

We glean details about his career life and gruff demeanor through his no-nonsense interactions with his secretaries and business partners, most clearly illustrated when his secretary asks why she even bothers with his schedule because he routinely cancels his reservations. “You don’t know anything about society, Marie. You don’t have the satisfaction of avoiding it.” Fincher, along with screenwriters John Brancato and Michael Ferris, so thoroughly flesh out van Orton’s pathetic existence that we understand that even a slight deviation from his norms will disrupt his psychological well being.

Reluctantly dining with his wayward brother Conrad (Sean Penn) to celebrate his birthday, Nicholas is presented with a unique birthday gift—a card for Consumer Recreation Services, a company that specializes in crafting games specific to the player. It’s a shady and mysterious operation, one that Nicholas is naturally hesitant to engage with because there’s too much he doesn’t know. But what else can you get for a man worth $600M? Nicholas soon finds himself undergoing a time-consuming barrage of psychological and physical tests in the CRS office. Unaware of even the most basic parameters of the game, or its moral, physical, and legal boundaries, it begins suddenly when he arrives home and finds a clown lying in his driveway in the exact spot where his father committed suicide.

And very quickly the seams of reality and cinematic convention begin to split. As we experience the film through the eyes of Nicholas, our own sense of what the game entails gradually expands along with his. At first, it seems like a large-scale practical joke when he’s dealing with the clown, some distasteful vandalism, and mysterious notes. Even when a waitress spills drinks on him, only to confess later that she had been put up to it for a couple hundred dollars, we can still accept that maybe it’s all just a big dumb gag. But then Conrad appears again, frantically confessing that he is under attack by CRS, that his own game is now out of control. Unhinged, Conrad flees from his brother’s presence when he suspects that Nicholas is in on the scheme against him, which heightens the sense of surreality but drastically erodes any solid foundation for the audience’s expectations to rest upon.

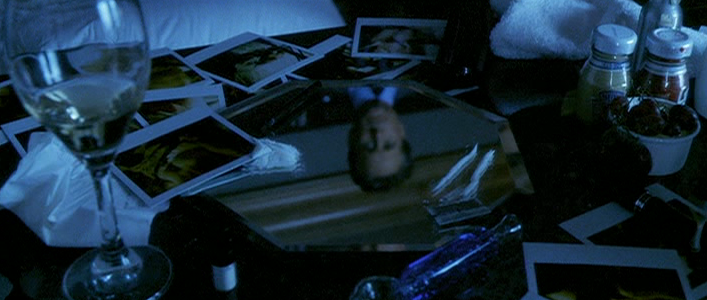

Our conception of the scope of the game expands again when Nicholas discovers an apartment that has been hastily furnished to appear lived in—he is tipped off by a smoking lamp, finding the price tag to be resting on the lightbulb; then he discovers that the refrigerator is empty and the books on the shelf are fake panels. We begin to suspect every line of dialogue may be a setup, every physical place may be a front, and every character besides the passionless tycoon might be in on the scheme, which proves to be much more sinister than a mere game.

Deborah Kara Unger and Sean Penn are stellar in their supporting roles, but it is Michael Douglas who dominates. He’s in virtually every scene, and serves as both the protagonist and the lens through which we interpret and react to the game. Having won Best Actor for his portrayal of a similar character in Wall Street, Douglas gives a nuanced performance that enjoys playing with our expectations and associations with that character.

But The Game is a film that is more fun to watch than it is to dissect. The clichéd themes are shallow and unfulfilling, and it is difficult to empathize with the protagonist. But, as Brendan Hodges notes in his analysis of the film, if we view The Game as a metaphor for the movies themselves, we may find a viable lens through which the film holds up much better. Van Orton’s tests at CRS are akin to the tailoring of blockbuster films to appeal to the broadest demographic through data analysis and test screenings; the artificialities of the physical world are plot holes we would discover in every movie if we really wanted to look closely. Since van Orton is such an unlikeable character, this novel angle fortuitously shifts our focus onto the man behind the curtain—the shadowy CRS and Fincher himself. We are wowed by the illusions and point to the magician rather than the sucker being duped.

It’s Fincher at his most exploitative, but it’s great fun for its entire runtime. Solid camerawork, a dark color palate, and effective background music allow the director to build paranoiac tension through the use of atmospherics rather than quick editing and jump scares. I still don’t think the ending feels quite right, but I enjoy much of what Fincher does here.

Sources:

Hodges, Brendan. “The Game Movie Review and Analysis”. The Metaplex. 26 September 2014.