“If we stay here much longer, she’ll have me sewing flags, like Betsy Ross.”

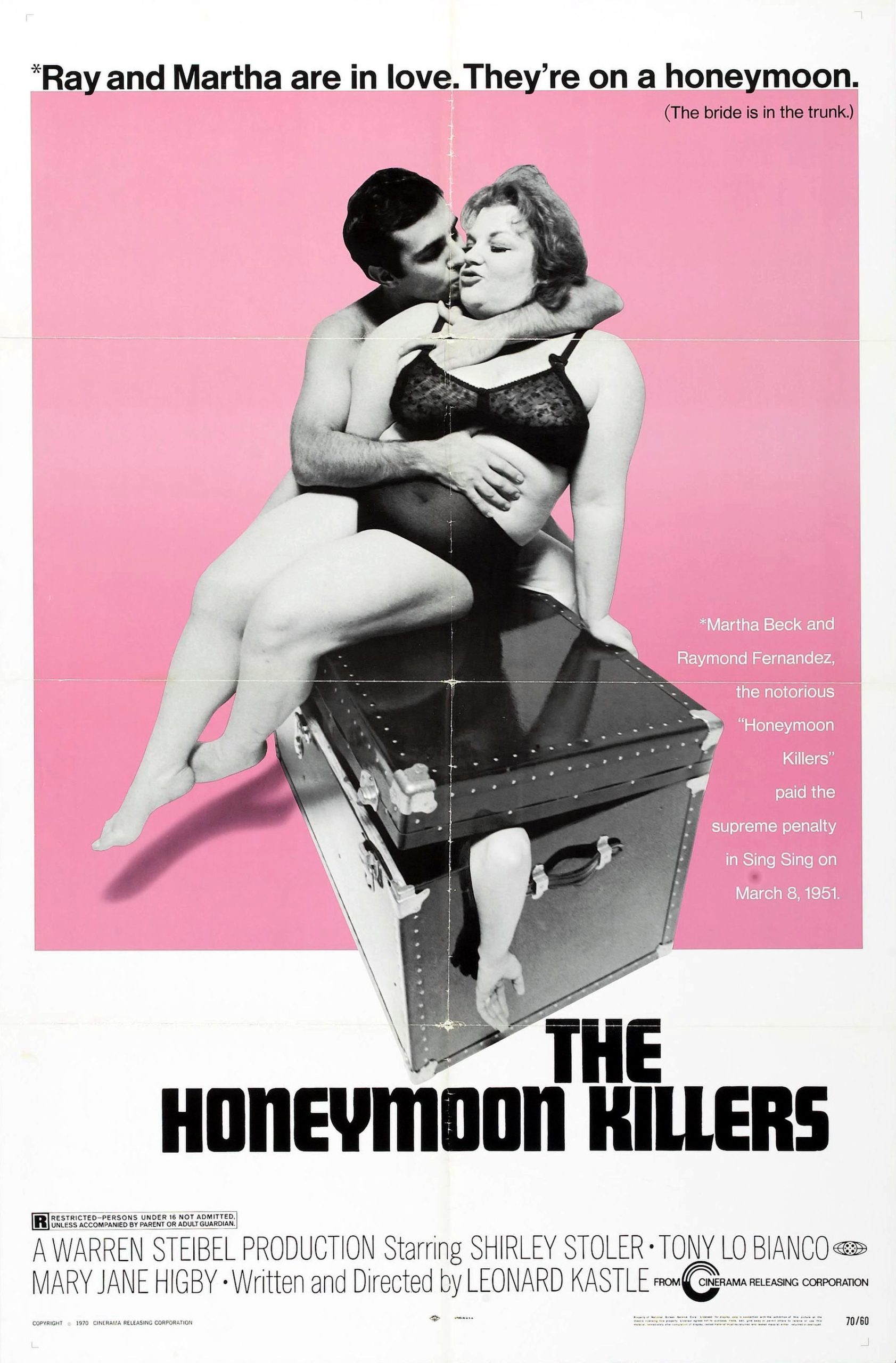

In the late 1960s, wealthy investor Leon Levy befriended Warren Steibel, the longtime producer of public affairs show Firing Line. Claiming his new friend was a genius, Levy asked Steibel how much he would need to make a film—not anything specific, just a film. (I agree with Steibel when he said, “Everyone needs a friend like this.”) In the end, Levy tossed his new pal a cool $150k and let him have at it. Foregoing the lush production values of regular Hollywood fare, Steibel settled on a grimly realistic depiction of a news story that had captured the national attention over a decade prior—“The Lonely Hearts Killers.” Suspected of wooing, robbing, and then killing as many as twenty single women who had answered their personal newspaper ads, unusual lovers Raymond Fernandez and Martha Beck had posed as brother and sister and taken their victims unsuspecting. They were sent to the electric chair in 1951 at the curiously named Sing Sing Correctional Facility.

Their exploits were initially set to be immortalized in celluloid by untested director Martin Scorsese, who had just wrapped his debut feature, Who’s That Knocking at My Door? Before anyone knew his name, the exacting director was looking to make a stylistic statement with The Honeymoon Killers. But artisanship was not exactly what the production of the schlocky exploitation flick was looking for. And so he was fired, and in stepped industrial filmmaker Donald Volkman, who similarly lasted only a short time. Finally, Leonard Kastle, an opera composer and Steibel’s roommate, took over the directorial duties. Initially, Kastle had been tasked by Steibel to help pore over the court records. Then, due to budget constraints, to write the screenplay. He was not supposed to direct—it just kind of happened that way. It is the matter-of-fact, immediate style employed by Kastle and cinematographer Oliver Wood that gives the film its sense of kinetic energy.

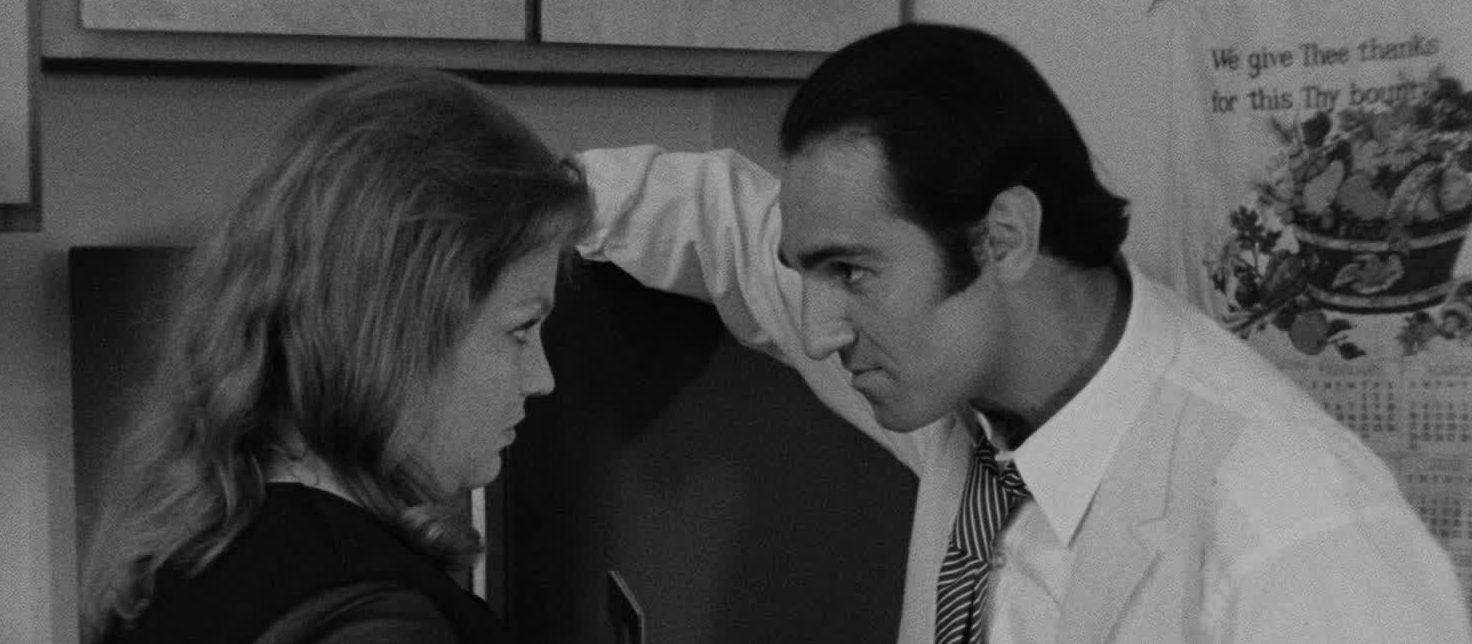

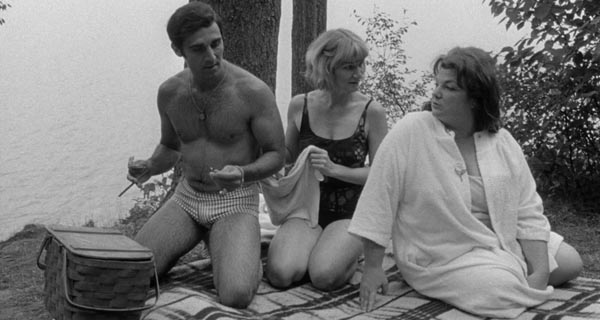

Tony Lo Bianco and Shirley Stoler, both stage actors transitioning to the screen, inhabit our main characters and carry the film (truthfully, the best of the rest of the performances might be flatteringly called “wooden”). Martha Beck (Stoler) is a grumpy nurse supervisor who is swindled by the sleazy conman early in the film. Stoler is great throughout, chewing scenery and spitting her vitriol at anyone who will listen and some who won’t. She falls in love via written correspondence and invites Ray (Lo Bianco) over for dinner at the house where she lives with her mother, where he sleeps with her and then rips her off. Undeterred, Martha tracks him down and forcefully integrates herself into his life. She willingly dumps her mother in a nursing home (in real life it was actually her children she left behind, leaving them at a Salvation Army shelter when she left to stay with Raymond in New York) and begins posing as Raymond’s sister while he runs the same game on a string of lonely ladies.

Although the events depicted are not actually funny, the film manages a kind of dark comedy in the way the couple’s victims are portrayed. In the interest of storytelling economy, the pursuit of each woman is given only a modicum of screen time. And so we witness these ladies going off to get married on a whim to some slimy playboy who looks and acts exactly like he’s going to leave you high and dry. In reality, their wooing was probably on the order of a few months, rather than the few days the film shows us. Even given the liberties taken to whittle down the runtime, the scams that these women fall for are completely unbelievable. But, I mean, they actually happened so apparently these ladies were just that airheaded. At one point, they are discussing with one of their targets and their target’s BFF the fact of their siblingship, and somehow it doesn’t strike either of them as odd that she is a pasty, overweight, brash hothead and he is a smooth talking slimeball with a thick Spanish accent. They’re clearly not related, and as Harry Morgan says in The Apple Dumpling Gang, they “go together like whiskey and ice cream.”

One of the noteworthy elements of The Honeymoon Killers—whether it is intentional or a result of the docudrama style that seems to have come about accidentally—is the starkly deglamorized portrayal of its lurid elements. In the wake of Bonnie and Clyde, films featuring gratuitous amounts of blood and sex were becoming mainstream as New Hollywood took over for a brief time. And though The Honeymoon Killers is overshadowed by Bonnie and Clyde and Badlands, it brings a unique flavor to the table with its blunt rather than stylized depictions of violence. Consider, for instance, a later scene in which Raymond and Martha’s cover is blown. Frightened and in an unfamiliar place, Raymond’s latest bride-to-be loses control of herself, so he pounces on her and begins mercilessly strangling her. Martha finishes her off with a blow to the head from a claw hammer. Creative special effects involving condoms and red dye make the scene viscerally real, but it is stripped of all pretense. The blunt camerawork makes the viewer grossly aware of their intrusion on the horrible act, with no stylistic barrier to make it artificial. At times, I was reminded of the black comedy Man Bites Dog and its similarly deadpan depictions of brutality.

But more than any of its narrative elements, what stands out the most to me are the mild inventiveness and the lack of polish. I mean both of those things in the best way possible. The film moves easily from one scene to the next, never lingering with aspirations of sophistication or grandeur. The filmmaking team seems intent on making something worthwhile but are not concerned with making high art. Instinctively, the on-the-fly production arrived at an unpretentious recipe that works well for the shocking source material. It leans into its deliberate pace, ratcheting up the disturbing tone and making the audience squirm with discomfort. I prefer the stylized version of crime, but this has its place; and the audacity required to just go out and make a film, even if your getting funded by your rich friend, is always to be admired.

Sources:

Grimes, William. “Behind the Filming of ‘The Honeymoon Killers’”. The New York Times. 20 October 1992.

Scott, Sam. “Martin Scorses Movies We’ll Never Get To See”. Looper. 8 March 2021.