“A thousand leaves mingle in the misty breeze. Plump brown chestnuts pummel the ground, yet I remain unharmed. The cold spews scorn at summer’s dying twitch, which with a last lazy stroke warms my limbs aching from another assault. Without trumpets or banners, see it. Here it comes, the splendid autumn.”

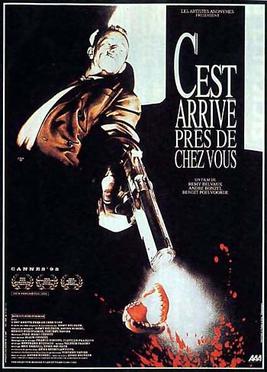

Man Bites Dog is not for the squeamish. Shot as a mockumentary, it depicts the life of a happy-go-lucky serial killer. While many of the killer’s antics are hilarious, the nebulous line of good taste is frequently crossed, leaving the viewer shocked and bewildered. These heinous moments are almost too profane to engage with, and yet that ultimately helps the film make its point.

Filmmakers Rémy Belvaux, André Bonzel and Benoît Poelvoorde made the film while they were students—it was shot in black and white and on a shoe-string budget. The premise was generated while trying to think of ideas for films that could be made inexpensively, which gives it some points on my scorecard regardless of the content. Each of the co-masterminds has a part in the movie and portray characters with the same names as themselves, with Poelvoorde starring as the serial killer.

There are certainly admirable elements here—the creative production choices (based on the limited budget), Poelvoorde’s acting abilities and natural charisma, the dark humor early in the film—but too often the intentionally provocative elements overshadow the genuinely good parts. I laughed out loud at one of the first scenes, in which Ben describes how much ballast must be added to a dead body for it to sink to the bottom of a body of water, then cuts to him dragging the body to an overlook and pushing it into a shallow quarry. The humor is not in the fact that a serial killer must consider how much weight to add to the body, but that such deliberation is included in the script and Benoît’s obvious delight in describing this trick of his trade.

In another early scene, Ben pursues a man into an industrial building. Although the team must remain quiet so as to keep their whereabouts unknown, Ben insists that Rémy capture footage of two mating pigeons as he takes time to earnestly recite a poem about them. Later, in the same scene, a firefight breaks out, and the crew’s sound man is killed. As they try to locate the shooter, Ben asks if the cameraman can use his zoom lens to help him search.

Don’t get me wrong, I found these scenes legitimately funny. However, in several scenes that are not worthy of description, they push things much further. My gripe with these scenes is not their graphic nature; it is their graphic nature paired with an absence of any dialogue to mask the crude text with humor. It’s plain old depravity.

If every element of a film must serve a purpose, then the only purpose of these scenes must be to shock. Okay then, I am shocked; but that doesn’t lead to any sort of satisfaction. And I think that is the point—to lure the viewer in, blending comedy with nightmare, gradually reducing the humorous reprieves until the audience is left appalled upon the realization that they have been cheering on a diabolical fiend for over an hour. It is an extended visual essay actually criticizing violence in film, pointing the finger at the audience who has collectively inched its way toward such a cinematic experience. If the humor did not drop out of the film partway through, I think I would have liked it more. Viewing the film as a sort of social commentary on how our minds have been warped by the barrage of violence in film throughout the years, I can appreciate it more, but not truly enjoy it.

While Belvaux and Bonzel essentially play themselves in the film (as director and cinematographer), Poelvoorde as the “protagonist” is the key to the film having legs at all. The character of Benoît is a sophisticated amalgam of traits both noble and criminal. He is loyal to his family (portrayed by Poelvoorde’s real family, who were reportedly unaware of the character’s occupation until the film was released). He is always eager to share his professional knowledge with the film crew, and is charitable with his “earnings,” funding the documentary when the crew runs out of money. He composes and quotes poetry and speaks eloquently about the problems with the current urban development plan. He plays chamber music with his girlfriend. But he also garrotes women, smothers children with pillows, and hides bodies in concrete.

The film crew (and the viewer) are persuaded by Ben’s charisma, and eventually instead of documenting his endeavors, they begin aiding in his activities. When he kills an African American nightwatchman, he refuses to touch him for fear of AIDS, and the film crew obligingly drags the body away for him. When his frequently utilized reservoir is drained and the remains of the bodies Ben has dumped there are visible, the crew is responsible for covering them up. At his birthday party, Benoît (perhaps accidentally, but perhaps not) shoots a companion in the head. The rest of the guests act as if nothing out of the ordinary has occurred, blood sticking to their faces as they pour more champagne and give Ben his next present.

As was discussed above, midway through the intentionally shocking elements are ramped up, and the humor that cleverly endeared Ben to the audience is dropped. At this point, we are meant to choke on our black laughter and step out of the film itself and consider ourselves and our own desensitization; we are not only allowing our media to be saturated with violence, but complicit in its gradual pervasion. Though released before the onset of reality television, Man Bites Dog uses the formula—though instead of encouraging mere voyeurism, it intentionally pushes its audience toward guilty contemplation. The film seems to be asking the viewer where the line should be drawn. If this is one step too far, what made the step before it okay? If the documentarians are okay filming a murder, why not take part in it? And as the viewer, if it was okay to cheer on the grotesquerie when it was funny, why not when it is deadpan?

As a social commentary in the guise of a documentary film, it works brilliantly. I am a bit concerned by the fact that had the comedic elements remained consistent throughout, I don’t think the critique the film is making would have dawned on me—I would have just thought it was a dark comedy. I probably would have enjoyed it more, but would have forgotten it quickly.