“They say some of the boys coming back are coming back real confused.”

In 1982, Bruce Springsteen released the somber, moody Nebraska, an album that was at odds with his usual youthful optimism. It’s a sparse, acoustic-driven collection of story-songs about criminals, outsiders, and blue collar characters facing the challenges of life, many of them written in the first person. He recorded the entire album on a four-track cassette recorder with the intention of recording the songs with the E Street Band, but felt that the demo versions suited the personal nature of the material and released them in their unpolished state. The fifth song on the album, “Highway Patrolman”, tells the story of Joe Roberts, a golden boy who became a police officer after his small farm went out of business; and his outlaw brother Frankie, a Vietnam vet who can’t keep himself straight. It features only an acoustic guitar, some subtle harmonica, and Springsteen’s voice, and includes the memorable chorus line: “Me and Frankie laughin’ and drinkin’, nothin’ feels better than blood on blood.”

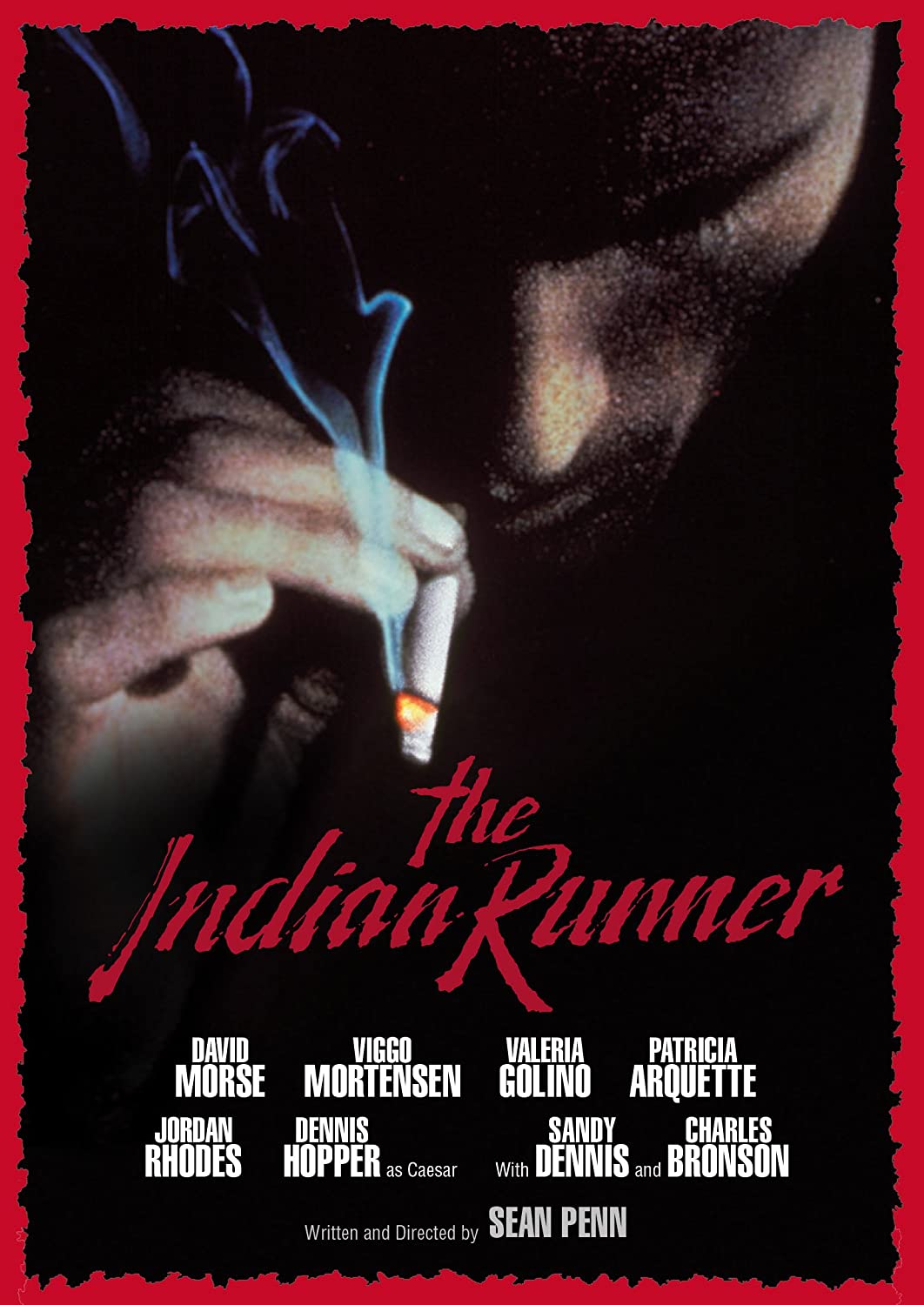

Though his best acting performances were still ahead of him, Sean Penn was already a rising star when he decided to step behind the camera for the first time. After passing the idea around to several writers, he eventually hunkered down and wrote his own screenplay based on Springsteen’s song, which proves unexpectedly poignant and skillfully crafted. It’s basic outline follows the structure of the song—Frankie (Viggo Mortensen) returns from Vietnam, his brother Joe (David Morse) tries his best to help him straighten his life out, ultimately turning a blind eye when Frankie crumbles under the weight of family tragedy and personal responsibility. While Penn occasionally gets a little bit too stylistically indulgent, which some may dislike but I enjoyed, his writing imbues his characters with humanity. The relationship between Frankie and Joe is the centerpiece, but Joe’s wife Maria (Valeria Golino), Frankie’s pixie girl Dorothy (Patricia Arquette), and the boy’s father (Charles Bronson) are all given adequate material to flesh out their characters into authentic people, giving a solid base for Penn’s meditation on the bonds of blood to rest upon.

“Highway Patrolman” is not really a story-song. It’s more of a slice-of-life tale, with only hints at a backstory and a haunting ending. The Indian Runner utilizes that outline, but truly embraces the whole of Nebraska for its aesthetic. The gist of Springsteen’s austere album—that things like our genealogy, the draft, or the collapse of the economy can have damaging effects on a person; that who we are is not necessarily our choice but is heavily influenced by forces outside of our control—is kept intact. In Frankie we have a rebel with “debts that no honest man can pay.” But even Joe, who has lived a virtuous, law-abiding life, becomes haunted by a heavy burden when he shoots a man in self-defense. That these two men were once little boys, playing cops-and-robbers in the backyard (shown in clips of home video), is at the heart of the film. How could the same environment produce such divergent trajectories for these two men?

Frankie returns from Vietnam, covered in amateur tattoos, hair slicked back, cigarette permanently smoldering between his clenched teeth. He arrives in the middle of the night, spooking Maria, who leaves her slumbering husband undisturbed as she approaches the noise downstairs with a pistol drawn. He only stays long enough to meet baby Raffael before hopping on a train to blaze another trail into the unknown, never glimpsing the “Welcome Home Frank” banner that his parents have hung. It’s after this short reunion that Joe begins to realize that despite the constant mentions of Frankie in his absence—whether due to his wandering spirit or military service—the Frankie of his childhood no longer exists, and the man who he has become is a stranger. Mortensen does an impeccable job of realizing Frankie as a character in the rebel mold of James Dean or Marlon Brando, the charming rascal who can do you wrong and then sweet talk his way out of any consequences. In contrast, Joe is the golden child who is naturally inclined to goodness. Such a character could easily become trite and tasteless, but Penn’s careful writing paints him as a sincere person who has authentic love for his wife, his child, his brother, and his hometown. He strains to reconcile his own moral code with the failings of his family, handling each individual differently in an attempt to show them love. In several instances, he and Frankie engage in a verbal sparring game where their conversation consists of a series of rhyming lines. In another thoughtfully written scene, Joe returns from a visit with Frankie, and Maria, puffing on a joint, informs her child, “Don’t ever smoke this stuff in front of the law. You smoke this stuff in front of the law, the law gets upset.” Before he enters the house, Joe calls out to his wife to hide the evidence before he comes inside.

The deaths of their parents—their mother succumbed to disease, their father ate his gun shortly after—leads to a moment of reconciliation between the two, in which Frankie breaks down and apologizes for all of his shortcomings. Frankie and the pregnant Dorothy move into Mr. Roberts’ old house, Frankie gets a job, they get married. But Frankie’s demons never give him respite for long, and when he feels like life is pinning him down he resorts to violent outbursts. After a particularly disastrous fit of rage, intercut with footage of Dorothy giving birth to Frank’s child, Joe realizes that he must let his brother go—there is nothing more he can do for him.

The nebulous origins of Frankie’s bad streak give the film an authenticity that feels lacking in film’s where everything is tied up neatly. We all have a family member or close friend who at some point in their lives veered off course and seems to have no desire to realign themselves. Sometimes the reason is too multifaceted to be articulated and that is how we are to understand Frankie. In the film’s most crucial scene, the brothers argue about the hands that life has dealt them. In the end, though their views conflict and Frankie seems only be able to grasp futilely at a coherent understanding of himself and the world, Joe agrees with Frankie that the deck is stacked against them; he simply chooses to have a different response to his circumstance than his brother, and his life is better for it.

I really enjoyed Penn’s script as well as Morse and Mortensen’s performances, but I would be remiss not to call attention to the supporting actors. Charles Bronson’s tender portrayal of Mr. Roberts is quiet but assured, highlighted by his unprompted admission to Joe that he was wrong to negatively react when Joe chose to marry a Mexican woman; and his final phone call to his son in the middle of the night is heartrending even though it reads benign. Sandy Dennis, as the boys’ mother, is only on screen for a minute or two. Her character was suffering from disease and so was she, succumbing to ovarian cancer less than six months after the film’s release. Mortensen tells a story (link below) of an excised scene which showcased Dennis “working on a level far above the rest of us. The concentration and vulnerability that she invested in the scene were remarkable. Heart-breaking. The fact that most of us knew that she was dying of ovarian cancer as she showed us the emotional disintegration of the character made the experience all the more poignant.” Valeria Golino is fantastic as Joe’s wife, Maria, bringing a wonderful sense of vitality to her character and filling throwaway moments with compassion and humanity. Young Patricia Arquette handles herself admirably, and the bit parts for Dennis Hopper as a bartender and Benicio del Toro as a drug dealer are fun in their own way.

I would also like to call attention to the soundtrack. Although it does not include Springsteen’s song (which would have felt kind of weird, anyway), it includes Traffic, Jefferson Airplane, Quicksilver Messenger Service, CCR, The Band, Janis Joplin. Along with the vehicles and the proximity to the Vietnam War the soundtrack gently sets us in the 1970s rather than the early 1990s. In addition to the big names, some original blues riffs are supplied by stringed instrument virtuoso David Lindley and composer Jack Nitzsche.

I appreciate the deliberate untidiness of the script, and its surreal final scene provides a suitably indefinite resolution. Overwhelmed by the emotional weight of the moment, Joe imagines that his brother’s receding tail lights reverse course and stop before him, and his kid brother, equipped with toy revolvers and a cowboy hat, steps out of the vehicle. As the fantasy fades and Frankie speeds into the night, never to be seen again, Joe comes to accept that he still lives a blessed life. The film concludes with a quote from Tagore, a Bengali poet and philosopher: “Every new child born brings the message that God is not yet discouraged of man.”

Sources:

Mortensen, Viggo. “Missing Sandy Dennis”. Focus Features. 7 August 2008.