“When you come to the end of the line, with a buddy who is more than a brother and a little less than a wife, getting blind drunk together is really the only way to say farewell.”

For long stretches of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, it’s more of a vibe than a story—a sprawling, sun-soaked, multithreaded amble through the dying gasps of hippie era Los Angeles: Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie) taking in her performance in The Wrecking Crew at the Fox Bruin Theater; her neighbor, former television cowboy Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio), pep-talking himself through a hangover for a turn as the heavy in a pilot while mulling over an offer from an agent (Al Pacino) to go make Spaghetti Westerns; his stuntman/chauffeur/handyman/best pal Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt), out of work amid rumors that he murdered his wife and assaulted Bruce Lee (Mike Moh) on a movie set, feeds his pitbull, fixes Rick’s TV antenna, and gives a teenage hitchhiker (Margaret Qualley) a ride to George Spahn’s (Bruce Dern) Movie Ranch where they used to film Rick’s cowboy show, but which is now overrun by Charles Manson’s dirty hippie cult (Austin Butler, Dakota Fanning, Lena Dunham, Madisen Beaty, Mikey Madison, Maya Hawke, Sydney Sweeney).

Writer-director Quentin Tarantino is a fan of “hangout” movies (citing Rio Bravo as his favorite), and that’s essentially what the first two hours of this film are, albeit in addition to hanging out with these fun movie personas we also hang out with Hollywood itself, as Tarantino packs his margins with homage, gossip, legends, and filmmaking jargon. One central segment that’s both hilarious and sneakily emotional has DiCaprio filming a couple of scenes with Timothy Olyphant and Julia Butters for his guest spot on Lancer. There are tons of radio ads, DJ banter, old pop hits, forgotten B movies, vintage billboards, old-fashioned theater marquees, drive-in theaters, classic cars… it’s got a little bit of American Graffiti in its DNA. But I mean, this is a guy who made theater operations and film criticism key elements of his WWII revisionist epic. What do you think he’s going to do with a story about the movie industry?

One of the film’s many achievements is that it embraces the challenge of recreating its period locations—which is straightforward when you’re filming a scene situated on a Western backlot or in a Beverly Hills home, but not when your star is cruising down Hollywood Boulevard in a Karmann Ghia with the windows rolled down and other old-timey cars criss-crossing on the overpass—that requires a concerted and expensive effort that most directors aren’t fussy enough to bother with. But Tarantino is and he wants to show off his hagiographic recreation. Ace cinematographer Robert Richardson obliges him with a bunch of luxuriant passages that exist solely to let us soak up the ambiance of this lavish period production design.

And but so Tarantino gives us this extremely warm-hearted but also somewhat skeptical view of this specific era and pocket of cultural history and his characters’ faded dreams, but we know what’s coming: specifically, in this film’s immediate path, are the Tate–LaBianca murders, but also Altamont, My Lai, the Zodiac Killer, the Chicago Seven, the Stonewall riots. This hovering black cloud of cultural unrest is personified by Charles Manson (Damon Herriman, who also portrayed the cult leader in Mindhunter), who only appears briefly, but whose cult of youthful, murderous hippies killed Sharon Tate in real life. I would imagine most movie lovers and junk culture fiends to whom this film appeals in the first place would be aware that the very pregnant Sharon Tate and her ex-fiancé Jay Sebring (Emile Hirsch) were indeed murdered on the night of August 8, 1969 (she was the wife of famous movie director Roman Polanski, of Rosemary’s Baby and Chinatown and The Pianist fame)—but, as he did with Inglourious Basterds, Tarantino remixes history in a satisfying manner, and in much the same way, too, giving his protagonists a chance to unleash righteous violence upon the perpetrators of evil who did not meet such fates in the history books. Indeed, many of the cultists who carried out the killings are still alive today! They are very much not alive at the end of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. “Is everyone okay?” Sebring asks Dalton in the aftermath, a Saint Peter figure guarding the pearly gates of Dalton’s version of heaven. “Well, the fuckin’ hippies aren’t,” he stammers.

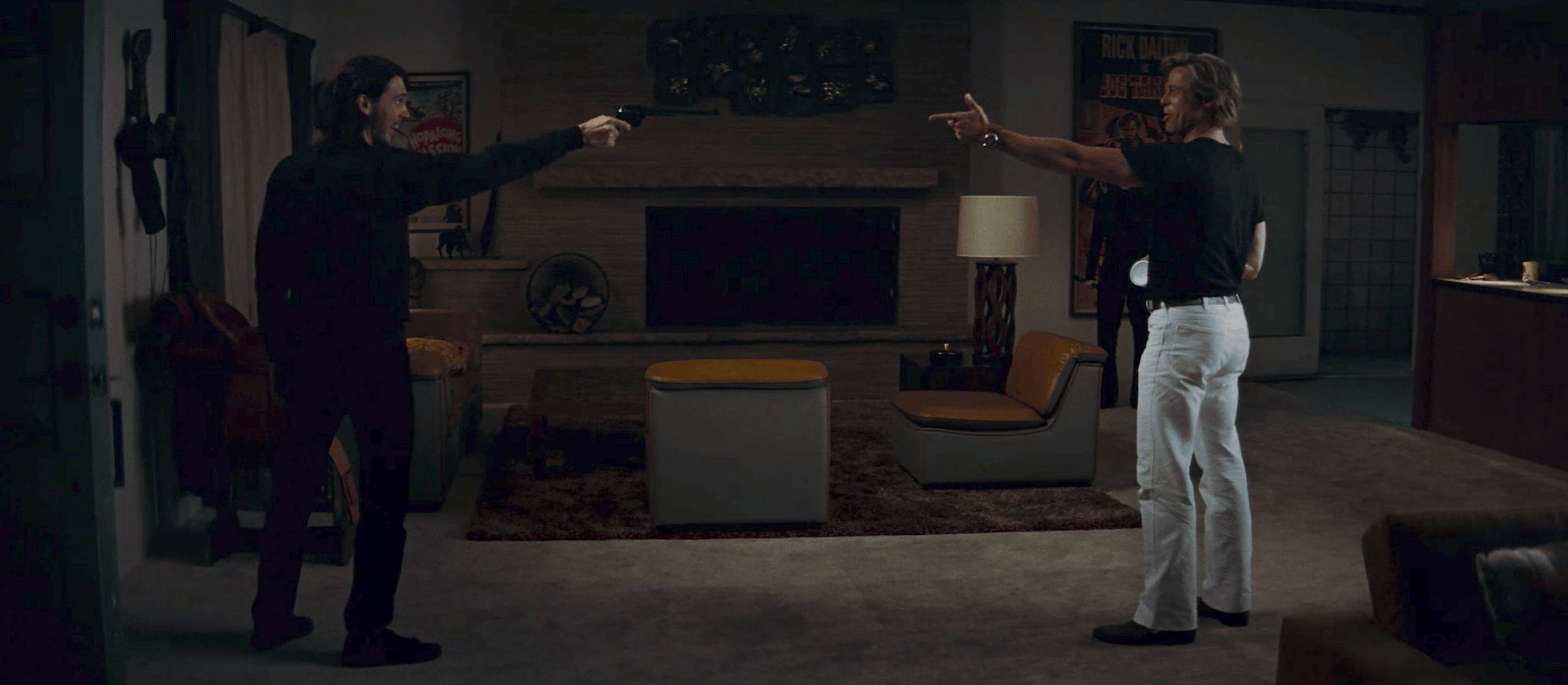

I remember sitting with a giddy smile on my face throughout the finale when I saw it in the theater (on my honeymoon, no less), and I found it even funnier already knowing how it was going to play out. Brad Pitt, who has always been a great character actor with a leading man’s good looks, and who won his only acting Oscar for his performance, walks off with the film as he gives us hilarious deadpan comedy and slapstick gore when Dalton’s home is invaded while Booth is under the effect of an LSD-dipped cigarette sold to him by one of those dirty hippies his boss hates so much (Perla Haney-Jardine, the daughter from Kill Bill: Volume 2). Cliff Booth is less concerned about the social and structural changes than Dalton, whose livelihood and social status depend on the status quo. By contrast, Booth is bemused and intrigued by the counterculture movement but wise enough to turn down an uninhibited teenager’s offer of free love. He’s confident in his ability to make ends meet and carries himself with swagger and offbeat style. He can jump cars over bridges and fix stuff and fight with casual grace. He’s an emphatically cool, masculine figure, but he also lives in a junky trailer and has hints of a dark side. When Dalton’s drunken bathrobe tirade redirects the hippie’s attention to his own home, Booth doesn’t back down from the ensuing fight even though he’s tripping. In fact, he seems to revel in it. He doesn’t see these Manson Family zealots as cultural bogeymen, but tragically misguided hippie freaks, a tainted version of a counterculture that he otherwise kind of digs. The free love killers themselves aren’t even all that bad, it’s just that they’re standing there in the living room with knives and guns. They’re trying to be as menacing as possible and he’s asking if they’re even real with a half smile, so high throughout the Mexican standoff that he initially uses a finger gun, a comedic goldmine of facial expressions and exquisite line readings. And when he confirms that they are not figments of his imagination and are, indeed, trying to kill him, he unleashes the gonzo carnage that has been kept bottled up throughout the film. After one of them, half mutilated by the pitbull, flops into Dalton’s pool and alerts him to the situation, he springs into action, firing up a functional flamethrower he had somehow managed to keep in his personal possession after using it in a movie. Since we’re altering history, I was kind of hoping for a Cliff Booth–Bruce Lee tag team massacre of Manson himself, but this is satisfactory and, in this imagined world, would probably replace the Manson murders themselves in the popular consciousness.

Cinema history has always been important to Tarantino, and if at times throughout his career he could have been accused of stealing all his best bits from the directors of yore and offering superlatively entertaining but ultimately hollow pastiche, and if Once Upon a Time in Hollywood emphatically reinforces the director as a talented video clerk fanboy with an encyclopedic knowledge of genre film history, it also suggests he may be evolving into something resembling a mature storyteller capable of genuine emotion just as the self-declared end of his career is coming into view (he’s always said ten features, and, though it takes some clever numbering, he claims this one as his penultimate work). He’s done period dramas before (The Hateful Eight, Django Unchained), and even his contemporary films exist in a movie world of 1970s chic, but where he usually resurrects and repurposes the past, here he is actively mourning its passing, acknowledging it was not an idyllic utopia while looking warily toward the future, intrigued and repulsed by the perverted youth who’ve taken over the culture but willing to adapt to the new milieu. Speaking of perversion, Tarantino is surely aware of the foot fetish narrative—how his films almost always feature uncomfortable closeups of bare feet—and he totally embraces it here, just as he embraces his reputation for excessive violence by having Cliff slam one of the hippies faces against a table again and again until there’s nothing left. Robbie and Qualley both have extended sequences with their grungy feet in prominent view, and even DiCaprio’s soles get a moment in the limelight. But I digress.

His other idiosyncrasies remain intact: rampant profanity, fake stuff (movies, shows, dog food brands, and how about Cliff removing a wig that looks exactly like his actual hair before fighting Bruce Lee), entire segments slipping into stylistic emulation of some sort. There’s jump-cut narration (by Kurt Russell, who also appears briefly as a stunt coordinator alongside actual stunt coordinator also playing one in the movie Zöe Bell) that summarizes key plot developments so impactful that you wonder why they don’t have their own scenes, and at one point he basically just lists Italian filmmakers he likes. He utilizes another crop of fringe actors who deserve more attention (Luke Perry, Damian Lewis, Nicholas Hammond, Scoot McNairy, Michael Madsen, Martin Kove, James Remar). The sublime touch of the gone-too-soon Sally Menke is once again sorely missed, as her deft scissor hand would have, I believe, helped corral Tarantino’s gangly screenplay into a film that feels like it all builds toward its satisfying conclusion. There’s little here that’s not well made, but it tends to feel like a handful of disconnected vignettes that kinda sorta meet up at the end. I think Menke would have reduced Robbie’s screen time (even though Tate being alive and well is part of the film’s fantasy and Tarantino’s personal mythology), ditched most of the exposition-dump at the Playboy mansion, reshaped the Spahn Ranch sequence, been a little less hyperactive with the flash cut references and flashbacks, and, if they filmed any scenes, included a little something of what’s covered in the catch-up narration after the six-month time jump. Lots of Tarantino films are structurally awkward like this one, but they don’t usually have such prominent potbellies. But hey, you know what they say about potbellies.

I’ve kind of danced around the idea that Tarantino has matured as a filmmaker and I want to clarify what I mean. It’s no secret that his oeuvre is one big orgasmic celebration of genre film, mixing and matching scenes, scenarios, characters, soundtracks, and set designs from bona fide classics and underseen B movies alike. He appears to love any random old middle-of-the-road gangster film more than most people love their own kids. And that affection is on full display in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. It’s been a long while since I’ve seen most of his films, so take what I have to say with a grain of salt, but there’s a dark, reflective undercurrent here that I’ve never detected before, that considers the downsides of escapist fantasy cinema and the corrupt system that created them in their heyday—at least in passing, which, being honest, is as much as you’d want in a film like this. I certainly don’t want hyper self-reflexivity from Tarantino. Recall that this came at the height of the MeToo era, when the skeletons just kept tumbling out of the closet of Tarantino’s old pal Harvey Weinstein, a man who was a major player in the system that produced a bunch of films we all love. The signs of corruption on the periphery of the film—not to mention the humbling crisis of its protagonist and its bittersweet ending—suggest that Tarantino is exceedingly aware of the abusive, dog-eat-dog nature of the system, past and present, and that even though he is infatuated with the fantasies he’s conjured and remixed over the years, he doesn’t believe they can save us or that they reflect reality. Which is a somewhat devastating reflection to have at the twilight of a career dedicated to the fleeting magic of the silver screen. Even so, where before he wore his influences on his sleeve, here he is inviting us into the rhythms of an early life that led to his obsession with cinema and pop culture in the first place. It’s a much more thoughtful take on Hollywood’s moral landscape than Damon Chazell’s Babylon (which also stars Robbie and Pitt) and a more effective commentary on the power of art and the complex psychology of the artist and the need for human companionship than it will be given credit for, allowing us to connect with the Rick Daltons and Cliff Booths of the world but also child prodigies working with desperate old men and the makeshift family of disillusioned Pussycats and Texes and Flowerchildren and Sadies.

Its elegy, daydream, and intuitively expressive, mythopoetic revisionist history delivered with a loopy grin, indulgent and shaggy and schizoid and silly in all the right ways, that stirs up a bunch of discordant feelings and meditates on a lot of salient themes without making any sort of moral or political statement. I can understand why some people who are on the fence with Tarantino will fall on the wrong side with this one—especially those who approach film as a platform for creative moralists and polemicists, which Tarantino is not—but for those who click with his genre menagerie style of filmmaking and this latent vulnerability, it’s a treat.