“You are the eventuality of an anomaly, which despite my sincerest efforts I have been unable to eliminate from what is otherwise a harmony of mathematical precision.”

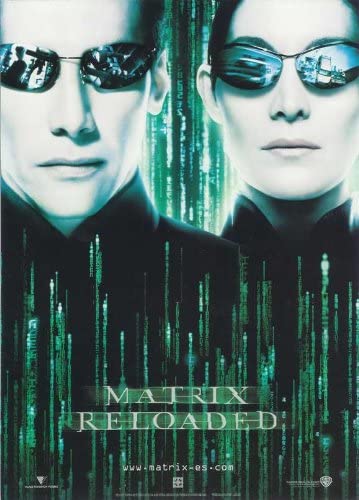

After delivering one of the all-time classic science fiction films in 1999 with The Matrix, the Wachowskis helmed a pair of follow-ups, filmed at the same time and released months apart in 2003. The Matrix Reloaded—the first sequel—was given the tough task of developing the universe introduced in the first film (which was incredibly fleshed out for only a film’s worth of exposition already, but left an endless string of questions open for debate) while attempting to one-up the original’s theatrical fight scenes and iconic spectacle. Though it falters in several unfortunate ways, it is a worthy follow-up and serves its purpose of expanding the universe of The Matrix very well.

An indeterminate amount of time has passed since the end of the first film. From the original film, we know that most humans are plugged into the Matrix, and only a small number have been awakened and live outside of it. We begin the story as sentinels are burrowing their way to Zion, the last human city, hidden near the earth’s core where it is still warm. While Commander Lock (Harry Lennix) dictates that all forces must participate in defensive and counter-attack efforts, Morpheus continues to believe in the prophecy given by The Oracle (Gloria Foster), flouting Lock’s order and taking Neo into the Matrix to meet with The Oracle again. She sends Neo on a quest that leads him to meet The Merovingian (Lambert Wilson), The Keymaker (Randall Duk Kim), and The Architect (Helmut Bakaitis).

The Merovingian is a rogue program that is kind of like a gangster of the Matrix underworld, who has an assortment of cronies working for him. His domain serves as a safe haven for outdated programs that are not ready to be deleted, and he is holding The Keymaker hostage. The Keymaker is also a rogue program who has the ability to create shortcuts between different areas within the Matrix, which allows Neo to reach the machine mainframe, where he walks through a door of light and meets The Architect.

In one of the film’s trippiest scenes, The Architect explains Neo’s purpose as a bank of television monitors projects Neo’s potential reactions to each statement The Architect makes. The Matrix is in its sixth iteration, and Neo’s role is to prevent the inevitable system crash that recurs due to the element of human choice that remains present within it. The past five iterations of The One have all accepted The Architect’s proposal: handpick survivors to rebuild Zion after it is destroyed by the machines. Otherwise, the system will crash, and kill every comatose human currently plugged into it. We already know what Neo will choose, and like the first film’s choice of pills, he now chooses between doors, going through the one that gives him a chance to save Trinity. As the film comes to a close, Neo learns that he can bend reality outside of the Matrix, though his effort puts him into a coma and he lies in a ward next to Bane (Ian Bliss), who became possessed by Agent Smith inside of the Matrix and let him out into the real world. “To Be Concluded” flashes on the screen before the end credits.

From the film’s opening scene, in which Trinity (Carrie-Anne Moss) backflips off a motorcycle, explodes a gas station and jumps from a skyscraper while shooting at her pursuers in slow-motion, it is clear that the action innovations of the first film will be relied upon heavily in the sequel. The Matrix ends with Neo (Keanu Reeves) flying for the first time, and he has now apparently learned enough to be a nearly untouchable superhero within the Matrix. Possibly due to the sheer amount of tricky choreography, slow motion, and impossible physical maneuvers, the action sequences seem to be sloppier than they were in the original. In a scene where Neo fights a gang of Agent Smith (Hugo Weaving) clones, the characters are very clearly computer generated, and the fight essentially turns into a videogame cutscene. While there is nothing inherently wrong with the use of CGI, the first film’s carefully planned uses of “bullet time” and wired acrobatics always seemed controlled and harmonious; they were oriented toward giving the audience an understanding of the altered physics of the Matrix and Neo’s budding capabilities rather than simply providing visual spectacle. The original was oozing with style, and its moments of off-the-wall acrobatics were restrained and well-timed; in Reloaded we have a classic case of “too much of a good thing” and the fight scenes tend to drag on and fail to sustain excitement.

A new set of philosophical ideas are presented in The Matrix Reloaded, though they don’t pull the rug out from under you in quite the same way that they did in the original. In The Matrix, the audience experiences Neo’s awakening as it happens, and we comprehend it because the Matrix tricked us too. In Reloaded, the ideas are mostly talked about instead of demonstrated, and so some of the oomph is lost. The idea with which Reloaded is primarily concerned is the contradiction of human free will within a deterministic universe. The Oracle raises the issue, The Merovingian presses it, and Neo seems to reject it. Though the film is explicitly raising the idea rather than presenting it organically within the plot of the film, it is at least there, so complaints can’t be for any lack of thought-provoking ideas, but rather for the lack of integration into the natural flow of the film.

Another foible that I am very sympathetic to is the ambitious attempt at transmedia storytelling. The streamlined plot of the film—which sees Neo and company jump from The Oracle to The Merovingian to The Keymaker to The Architect in rapid succession—only appears thin because it doesn’t include the full narrative. Captain Niobe (Jada Pinkett Smith) and Persephone (Monica Bellucci) play major roles in the film, but neither have a backstory or much character development. These elements are not present in the film because they are part of the videogame Enter the Matrix, which is not just a retelling of the film, but an integral part of the overall story. The game includes over an hour of live action footage that was specifically shot for the game (and is included in the documentary The Matrix Reloaded Revisited), and it even explains why The Oracle is portrayed by a different actress in The Matrix Revolutions (in reality, it is because Gloria Foster passed away before shooting her scenes for the third film).

The film begins with our heroes knowing that Zion will soon be under attack as they make decisions regarding their defense tactics. “Final Flight of the Osiris”—a short anime film that appears in The Animatrix but was originally shown in theaters before the film Dreamcatcher and was also available online—sets the stage for Reloaded by telling the story of a crew sacrificing themselves to warn of the impending assault. Another short film in The Animatrix, the aptly titled “Kid’s Story”, gives us some context when our protagonists arrive in Zion and Neo is shadowed by a young man who shows him great reverence. Without the context, we don’t know the character, and his presence feels tacked on and annoying. It is unfortunate that the Wachowski’s ambitions seemed to have outstripped the public’s interest in consuming various types of media to follow the entire story. While the films, the animated shorts, and the comics have held up well, advancements in technology and format have made the videogame almost impossible to play today (not to mention that videogames have improved much more in quality in the past two decades than cinema has). All of this being the case, I am not entirely sure how to judge the film—do I critique it solely as the sequel to The Matrix, or is it only fair to consider all of the other attempts at universe building outside of the realm of cinema?

There are a few areas where I feel the sequel improved upon the original, or at least filled in some holes that needed plugging. In my review of the original, I noted that the technology no longer appears futuristic as it did upon release, even contrasting it to the technology presented in Minority Report. In Reloaded, we are shown new technology that most definitely took cues from Spielberg’s film. It looks great and it makes sense given the context why the interfaces that operators like Link (Harold Perrineau) use are not state of the art. The elegant interfaces used by the controllers in Zion look great. There are a few tentative attempts at humor that don’t need to land for the scene to work (i.e. the scene doesn’t fall flat if you don’t find the lines funny), such as Neo’s awkward decision whether to sit or stand whenever he meets with the prescient Oracle. A few philosophical digressions (which, as I have mentioned, do not flow very seamlessly) take us down tangential trains of thought. E.g. One of my favorite scenes in the entire trilogy is when Councilor Hamann (Anthony Zerbe) takes Neo to the engineering level in Zion.

Hamann: Almost no one comes down here, unless of course there’s a problem. That’s how it is with people. Nobody cares how it works as long as it works. I like it down here. I like to be reminded this city survives because of these machines. These machines are keeping us alive while other machines are coming to kill us. Interesting isn’t it? The power to give life, and the power to end it.

Neo: We have the same power.

H: I suppose we do, but down here sometimes I think about all those people still plugged into the Matrix and when I look at these machines I can’t help thinking that in a way we are plugged into them.

N: But we control these machines, they don’t control us.

H: Of course not. How could they? The idea is pure nonsense, but it does make one wonder: what is control?

N: If we wanted we could shut these machines down.

H: That’s it, you hit it. That’s control, isn’t it? If we wanted, we could smash them to bits. Although if we did, we’d have to consider what would happen to our lights, our heat, our air.

N: So we need machines and they need us. Is that your point, Councilor?

H: No, no point. Old men like me don’t bother with making points. There’s no point.

N: Is that why there are no young men on the council?

H: Good point.

N: Why don’t you tell me what’s on your mind, Councilor?

H: There is so much in this world that I do not understand. See that machine? It has something to do with recycling our water supply. I have absolutely no idea how it works. But I do understand the reason for it to work. I have absolutely no idea how you are able to do some of the things you do, but I believe there’s a reason for that as well. I only hope we understand that reason before it’s too late.

The conversation conveys a lot of information and ideas in a very short time. It fleshes out the underground city, giving us a more thorough understanding of the citizens of Zion after only really encountering them for the extended rave scene. It raises the idea of humanity’s increased reliance on machines which few of us truly understand. It includes fun verbal sparring, and critiques the idea that age and experience leads to better decision making.

The biggest “whoa” moment in Reloaded is when The Architect explains to Neo that after the first Matrix iteration failed because humans rejected a perfect world, the next one struggled because humans needed the illusion of choice, even if it was subconscious. Given the choice, more than 99% of humanity chooses the Matrix, while those who reject it are given the illusion of free will as they are allowed to rebuild Zion. In the first film, Morpheus explained to Neo, “When the Matrix was first built there was a man born inside that had the ability to change what he wanted, to remake the Matrix as he saw fit. It was this man who freed the first of us and taught us the truth. When he died, The Oracle prophesied his return and envisioned that his coming would hail the destruction of the Matrix.” It can be assumed that this man was simply the previous version of The One, and that the prophecy that Morpheus believes in will crumble when he learns of Neo’s discovery.

There are a host of questions that are not resolved, that if examined closely would probably show some plot holes, but Reloaded keeps the ship right enough that there is still plenty left to be explored in The Matrix Revolutions. The same criticisms that could be made against the first film hold here as well, but a few additional missteps (like the bizarre tribal rave scene in Zion) knock this one down a few notches. The biggest issue is that as the scope has expanded the human angle has become washed out. The dramatic arcs are not robust which leaves the film feeling uneven and incohesive, and too many scenes are disconnected and simply setting up the concluding film. Even though it doesn’t approach the level of the original, it is mostly solid and a thoroughly engaging follow-up.

Sources:

Willems, Patrick. “Why it’s almost impossible to see The Matrix Reloaded as it was meant to be seen”. Polygon. 12 June 2019.