“Feel it. Reach. I wanted to teach you everything the earth is full of, Helen. Everything on it that’s ours for a wink and it’s gone. And what we are on it. The light we bring to it and leave behind in words. We can see five thousand years back in the light of words. Everything we feel, think, know, and share in words. So not a soul is in darkness, or done with, even in the grave.”

Arthur Penn’s The Miracle Worker is built around subject matter so uncommon and poignant, and carried by two performances so captivating, that it is easy to forgive its obvious flaws and corroborate the contemporary praise it received.

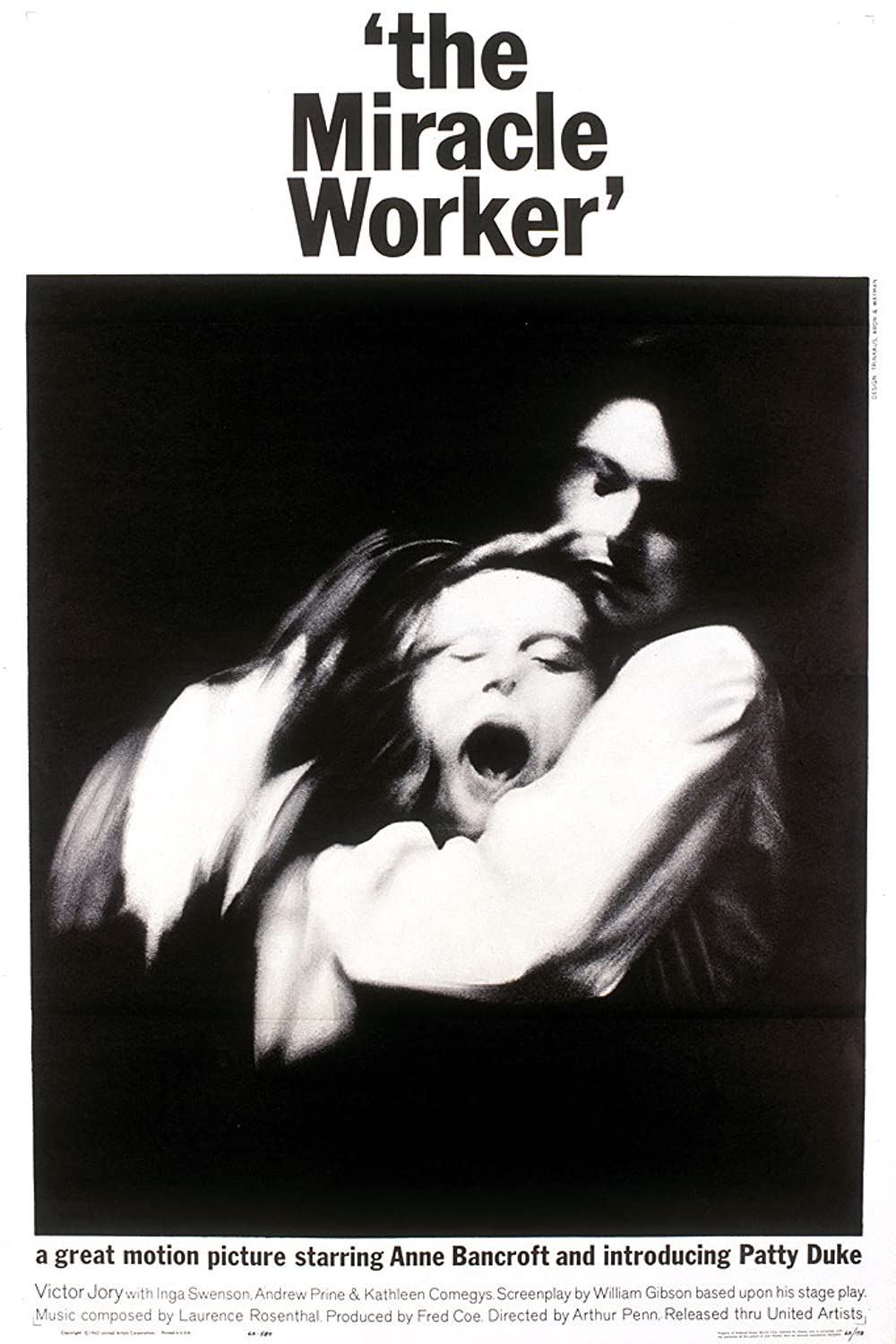

Centered on the tempestuous relationship between the deaf and blind Helen Keller (Patty Duke) and her ruthlessly determined teacher Anne Sullivan (Anne Bancroft), it relies quite heavily on its two leads, who wholly embody their characters and play off one another’s ferocity with breathtaking physical chemistry. The pair had honed their roles through hundreds of performances of the play on Broadway, and their impassioned, naturalistic performances allow Penn (who had directed them on the stage) to let his camera roll without cutting for gloriously long stretches. This plays out to fascinating effect as Duke’s performance is entirely non-verbal, relying rather on her countenance and the movements of her body. She touches the faces of others, mimics their expressions, flails her arms, swings her fists, spits food, throws silverware. All of this while remaining fully in character, staring off into space uncomprehendingly, movements uncoordinated and sloppy, as if she is truly moving through the world without sight or hearing. And yet her performance never feels contrived, hollow, or practiced. Bancroft, though inhabiting a speaking role—which includes a heavy dose of sardonic quips—is equally physical: grabbing, pulling, pinning, wrenching, dragging.

The bruising violence that the pair generate is most prominently on display in a scene near the middle of the film where Anne demands that Helen’s parents leave the dining room. They’ve become accustomed to Helen circling the table during supper, grabbing what she will from their plates, stuffing her face and letting the excess drop into a ring of waste on the floor. This practice allows them to have a time of peaceful conversation while Helen is docile. Anne finds this disgusting and spends the entire afternoon locked in the room with Helen, trying to teach her to eat with a spoon and use a napkin. Of course, Helen resents this and so the scene plays out for minutes on end as they tear the room apart in a wild wrestling match. By its end, food litters the floor, a half dozen spoons have been tossed randomly, Helen has eagerly gobbled up crumbs scooped up from under the table and then spat them in Anne’s face, and Anne has doused her pupil with a pitcher of water.

The frame story should be familiar to most viewers (at least, it was a commonly taught story when I was growing up): in the 1880s, Anne Sullivan, a sight-impaired graduate of the Perkins School for the Blind, accepted an appointment with the Keller family to teach young Helen, who had lost her senses of sight and hearing due to an illness in her infancy. Through persistent and diligent teaching, Helen Keller would go on to graduate from Harvard, write books, and give speeches (The Miracle Worker is primarily based on her autobiography, The Story of My Life).

The Miracle Worker only covers a brief period of Helen’s early life, up to and including the breakthrough that occurs when the sign language system Anne has been practicing finally clicks for her. It’s depicted in a piercing scene that comes right in the midst of a spat, Anne dragging Helen out to the water pump to refill the pitcher that she’s just tossed into her tutor’s face. Helen, feeling the water on her hand as it gushes from the pump, has a moment of insight that penetrates the darkness in her mind and recalls the single word she had murmured as an infant. “Wah… wah,” she says. Anne immediately comprehends that a breakthrough is occurring and follows Helen around the yard as she eagerly lays hands on the ground, the pump, a tree, a step, demanding that Anne teach her how to sign each of them. And all of a sudden she has grasped the fact that things have names, that she wasn’t just repeating hand motions as a trick but that she can use those movements to communicate. The rhapsody shared between teacher and student is evident, and Anne’s building sense of joy rises as she yells for the Kellers to come join them outside, the music swelling just when it should. It’s an uplifting, transcendent ending that feels entirely earned by the blood and tears that preceded it.

Unfortunately, when The Miracle Worker moves beyond the fierce dynamic at its center and tries to flesh out the backstory it woefully underwhelms. Trouble brews between Anne and Arthur Keller (Victor Jory), who merely wants his child housebroken and cooperative and could care less if she learns to communicate or thrives in any way. He speaks openly about an asylum to his wife Kate (Inga Swenson), whose primary flaw is that she cannot bear to be strict with her child. The writing here is a mixed bag, for sure, but the real problem is the way the tone moves unevenly between excessive melodramatics and farcical comedy, both of which clash terribly with the powerful drama that carries the film and don’t even succeed on their own terms. Penn also tries his hand at a few cinematic flourishes that bespeak a French New Wave influence—unconventional angles and hazy overlaid images to depict Anne’s memories. These are interesting touches but don’t really have an effect either way on the film’s quality.

Though the foibles are painfully evident, they’re overpowered by Duke and Bancroft, both of whom won Academy Awards for their cooperative powerhouse performance. A week after seeing it you will have forgotten most of its shortcomings, but not those two.