“May we not believe as we choose and allow others to do the same?”

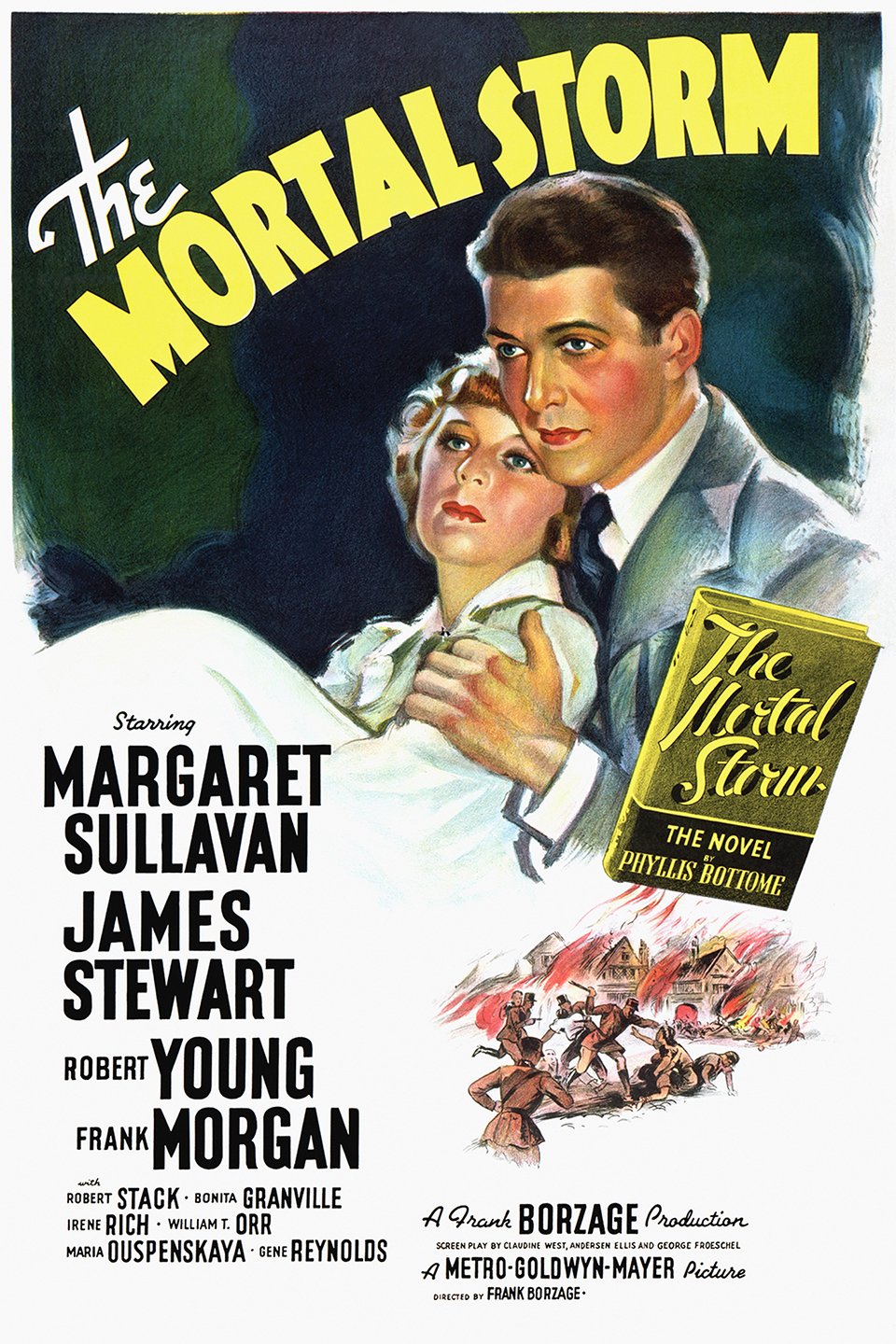

Frank Borzage’s The Mortal Storm stands alongside Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator as one of the few enduring anti-Nazi Hollywood films released prior to America’s formal entry into WWII. Its morally instructive depiction of a family, community, and nation quickly swept up and torn asunder by a poisonous ideology is historically significant—it led to the banishment of all MGM films in Germany—but it comes in the form of an exceedingly romantic, well-constructed melodrama that features James Stewart and Margaret Sullavan in their final screen pairing.

In a scene that is brilliantly and tragically echoed in the film’s waning moments, esteemed university professor Viktor Roth (Frank Morgan) happily celebrates his sixtieth birthday and his fruitful academic career along with his family and two close family friends. When a radio broadcast announces that Adolf Hitler has been appointed chancellor, the joyous occasion immediately turns sour. Professor Roth, a non-Aryan (the word “Jew” is never spoken), must watch as his two stepsons (Robert Stack, William T. Orr), both full-blooded Germans, eagerly dart off to a meeting of the Hitler Youth. Worse still is that their childhood pal Fritz (Robert Young), so recently engaged to Roth’s half-Aryan daughter Freya (Sullavan), goes along with them. The only Aryan left in the room is Martin (Stewart), a pseudo-pacifist veterinarian who favors the simple life and harbors romantic feelings for Freya. “Peasants have no politics,” he says when pressed. “They keep cows.”

And so what was once a tranquil little university town in the Bavarian Alps transforms into a hellscape overrun by brutal, arrogant, violent ideologues who burn books, shout political fight songs in unison, assault elderly citizens, and boycott college courses that teach against party doctrine. Against this new backdrop, which sees all detractors subject to increasingly harsh treatment, Borzage positions a defiant romance between Martin and Freya. Though it culminates in an achingly sweet improvised wedding officiated by Martin’s withering mother (Maria Ouspenskaya)—who is almost certainly saying a final goodbye to her son and new daughter-in-law even as she celebrates their new love—the romance never threatens to overwhelm the film’s larger points which are teased out in a concentration camp visit between Roth and his wife (Irene Rich), a nearly wordless conversation between the stepsons who must square their youthful fantasies with their eternal consequences, and a poignant coda that glides through the empty home that was full of love and hope such a short time ago. More so than the climactic ski chase or the overwrought closing narration, it’s that nostalgic final sequence that brings the film home, emphasizing themes of personal loss and hope for redemption.

A gripping indictment of the Nazi ideology that perhaps came too late for its desired political impact, The Mortal Storm remains a stirring reminder of the depravity of man and the precious value of liberty.