“Your brain gonna fry out here, you know that?”

Ever the opportunist, Roger Corman was fond of bankrolling the twofer—of sending his young film crews out into the field to shoot a pair of films with the production budget of one. This meant overlapping casts, reused props, costumes, and locations, but also plenty of opportunity for ambitious rookie filmmakers to try on a variety of hats. When Corman was directing his Nazis-on-skis flick Ski Troop Attack (in Deadwood, SD to cut down on costs), he tapped a young Monte Hellman to direct Beast from Haunted Cave using the same screenwriter, locations, and principal cast. After that, Hellman accepted a commission from Robert Lippert to make a pair of films in the Philippines with his friend Jack Nicholson (Flight to Fury and Back Door to Hell).1 With three films under his belt, two of them enjoyable collaborations with Nicholson, Hellman approached Corman with a script the pair had written together. Corman passed but said he would be willing to finance a Western—scratch that, he’d be willing to finance two Westerns, provided they shot them in his patented two-for-one style. And so Hellman and Nicholson found themselves out in the arid deserts and dusty canyons of southern Utah for six weeks shooting one script from Nicholson and another from Carole Eastman (writing under the pseudonym Adrien Joyce).

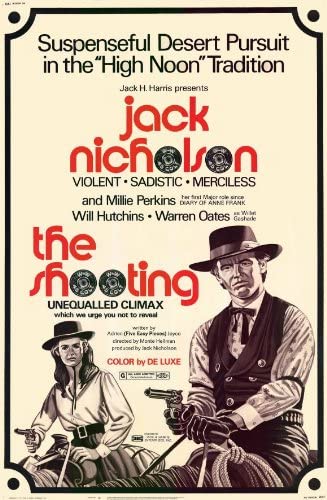

Working under the aegis of Corman, there were obvious constraints in budget and scope, but otherwise Hellman was allowed to operate with creative autonomy. He used this freedom to trailblaze a new kind of film—later to be called the acid western, a slippery subgenre marked by its counter-cultural influences, Spaghetti western stylizations, subversive violence, and formula-breaking structures. In the case of The Shooting, the first of Hellman’s audacious back-to-back productions, the focus is turned inward as three dodgy men are contracted by a mysterious woman to chaperone her on a journey through the barren terrain. The film opens as former bounty hunter Willet Gashade (Warren Oates) returns to a remote goldmine after a long absence to find his slow-witted partner Coley (Will Hutchins) in a frightful state. According to Coley’s frantic rambling, Gashade’s brother Coigne had accidentally trampled a young boy to death while in town and then fled the mining camp moments before an unseen assassin gunned down Coley’s sole remaining companion, a man named Drum (B.J. Merholz, seen only in flashback). The next day, a secretive woman (Millie Perkins, Hellman’s next-door neighbor at the time) arrives at their camp and offers Gashade and Coley a substantial sum of money to guide her to the town of Kingsley, but refuses to divulge the nature of her quest.

Gashade instinctively distrusts her—she’s rude from the start (preying on Coley’s infatuation with her but otherwise contemptuous of both men), refuses to give them her name, and when she arrives at the camp, she announces herself by putting her horse out of its misery despite its evident perfect health. Nevertheless, Gashade grudgingly accepts the job in hopes that he can track down his brother while traveling to Kingsley; the smitten Coley tags along for a lesser sum. Their journey is unpleasant and Gashade’s suspicions continue to grow as the woman liberally practices with her pistol. He begins to suspect she’s communicating her status to an unseen follower and he’s proved right when Coley unwittingly beckons Billy Spear (Nicholson) with his own random gunshots. Spear is a loose-triggered gunslinger with an evil grin that the woman had hired sometime prior and who seems intent on sadistically goading Coley into a fight. The situation grows uneasy as these reluctant companions march their animals to death and weaken in the sweltering heat, all the while uncertain of the object of their pursuit or the nature of their adversaries.

As the ambiguous mission grows increasingly unclear, it becomes evident to the viewer that Hellman is less interested in story than in character. More specifically, he employs the camera and the scissors to illustrate his characters’ gradually fraying states of mind. He conveys Gashade’s growing sense of paranoia not with tricky effects but practical ingenuity—lingering on the barren landscape, emphasizing the claustrophobia induced by the restrictive mountains, and cutting to disorienting close ups during conversation. Those conversations, often terse and confrontational, are brimming with verbose sentences and yet deliberately, uniformly lacking any concrete narrative clues. Hellman proudly claims to have started shooting the script on the tenth page in order to remove needless exposition, but the whole script has key pieces of info clearly left out. Even simple transitory scenes are marked by intentionally excised moments, like when Coley is suddenly riding on the back of Gashade’s horse, pitiful and emasculated, his own horse given to the woman when hers perished from exhaustion. This startling lack of narrative context transforms Gashade’s trek into a daytime nightmare as he stumbles forward without a metaphysical safety net toward a horrifying, surreal conclusion that plays out in slow motion, only tied to reality by a few stray lines of dialogue included at Corman’s request.

The Shooting was shown at a few festivals and was a minor hit in arthouse theaters in Paris, but in the U.S. it went straight to television and flew way under the radar. In the ensuing years, it garnered a following as critics like Jonathan Rosenbaum pinpointed it as one of the early films that kicked off a wave of opaque existential westerns. What’s fascinating to me is that Hellman was forced by the small budget (and a deal which would see Hellman and Nicholson paying Corman back if they went over it) to flex his creative muscles, which led to many decisions regarding cast size, shooting schedule, shot choice, etc. that echo the film’s philosophical underpinnings. It’s possible that some of the visual language is simply an inevitable product of the circumstances and critics have read too far into Hellman’s intentions, but whatever the case may be, The Shooting is impossibly good for its quick-and-dirty production, and Hellman left the shoot with an additional feature length film to boot. The Corman Film School helped many young directors cut their teeth before moving onto bigger and better things, but few produced such a strong picture while working for the man himself.

1. I’ve seen several mentions that Corman produced those two films, but the info that I’ve found indicates that is not true.