“Give me that baby, you warthog from hell!”

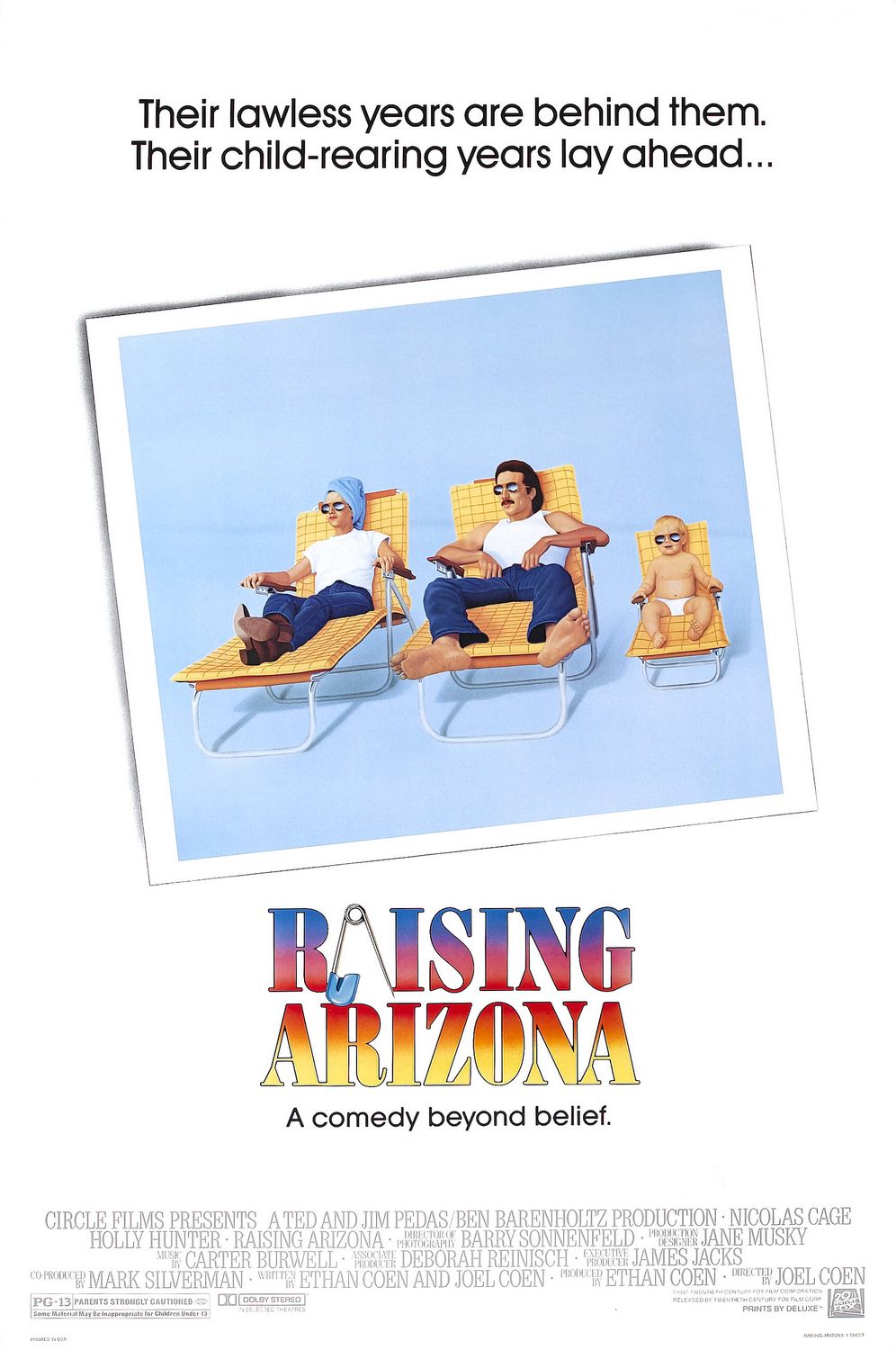

Maybe it’s the frenetic pace. Maybe it’s the brief runtime. Maybe it’s the manic performances from Nicolas Cage, Holly Hunter and John Goodman. Maybe it’s the somehow concise but loose script. Maybe it’s the mesmerizing overlap of feigned middle American realism and absurdist comedy. I don’t know exactly what does it for me, but I’ve watched Raising Arizona more than any other Coen brothers film. They’ve made probably half a dozen others that I prefer to this one, but there’s just something about it that beckons me to choose it time and again. Despite the fact that my wife “lost brain cells and IQ points” while watching it for the first time, I find Raising Arizona to be an extremely confident, intelligent, introspective, and downright funny sophomore effort from the Coens. It must be on a comic wavelength that only works for certain people. Having only one film under their belt at this point, the neo-noir Blood Simple, there wasn’t such a thing as “a Coen brothers film,” and so the superficially unpolished script, which gives prominence to unconventional characters and regional parlance and mixes moral conundrums with slapstick wasn’t really a known commodity. Their debut relied upon existing formulas, but Raising Arizona boldly announced a wild new voice in American cinema.

One of the Coens’ defining characteristics is their dense dialogue, and they showcase it here in full force. Their penchant for hickish dialect and repetition sets the perfect tone before the late title card even drops. Along with a nutshelled backstory of Hi (Cage) and Ed’s (Hunter) unconventional courtship, we are presented with a smorgasbord of characters and lines that are seemingly trivial but reveal, upon repeat viewings, careful writing, impeccable wit, and flavorful world-building. H.I. McDunnough, a frequent flyer at the Maricopa County Maximum Security Correctional Facility, falls in love with the lady police officer who takes his mugshots, jumping at the sliver of a chance when her “fy-ance” leaves her, and “walks in on his knees” to propose a marriage that will allow him to break free of his cycle of recidivism.

They settle down in a rundown trailer park and enjoy the “salad days,” which come to a screeching halt when Ed finds out that she is barren, ruining their plans to “have a critter.” Due to Hi’s checkered past, the couple are unable to adopt. Kept from having children due to “biology and the prejudices of others,” a heaven sent remedy falls right into their laps—the Arizona quints are born to the wealthy owner of an unpainted furniture store. By the time Ed and Hi kidnap one of the quintuplets—“I need a baby, Hi. They got more than they can handle.”—it is evident that Cage and Hunter are perfectly cast as the madcap couple. As they speed into the sunset with Nathan Arizona Jr. in their arms, the words “Raising Arizona” overlay the shot as a skittering banjo and a pitched yodel soundtrack their escape. So much narrative ground is covered in the sequence that it’s easy to miss how efficiently the story has been conveyed—subtle facial expressions, creative camerawork, voiceover, one-liners from minor characters; it’s truly a treat. The only issue I have with it is that it is so delicious that the rest of the film can’t help but underwhelm in comparison.

The problem with stealing someone else’s baby is that it’s kind of hard to hide, especially when a host of zany characters will be poking their noses around the old homestead. Coen regular John Goodman appears in his first Coen brothers role, portraying escaped convict Gale Snoats along with William Forsythe, who plays Gale’s brother, Evelle. The duo bust out of prison through a sewer pipe and hightail it to the McDunnough residence to lay low for a while, instigating a battle of wills between Hi and Ed. While I wish Goodman didn’t have to spend so much time literally yelling at the top of his lungs, he’s mostly a delight, and Forsythe is pretty good as an echoing companion. Frances McDormand, by now married to Joel Coen, plays the hyperactive Dot, who obliviously uncovers a bunch of red flags about the couple’s new baby when she begins pestering Ed with questions. It’s truly remarkable how much more confident McDormand seems only a few short years after her debut in Blood Simple, albeit in a smaller role. Even Trey Wilson, who portrays Nathan Arizona, gets a hilarious extended monologue and knocks it out of the park. (Unfortunately, Wilson died of a brain hemorrhage before filming began for the Coens’ Miller’s Crossing, in which he was cast.) But the film unequivocally belongs to Cage and Hunter, who are note-perfect in their roles. Cage’s delirious facial expressions and goofy vocal inflections are peculiarly mesmerizing as he portrays the torment of balancing family life with an on-again, off-again relationship with petty thievery—with an unloaded gun, of course, that way it’s not considered armed robbery. He is almost entirely a cartoon in his physical acting, but the script turns him into an practical philosopher trying to find his way through a nonsensical world. Hunter balances Cage’s antics with her own brand of humor that is kicked into high gear by the maternalistic nature of her character, encapsulated by her immediate outburst of tears upon holding Nathan Jr. in her arms for the first time. “I love him so much!” she bawls, racked with sobs.

The comedy would not be complete without its interwoven fever dreams. Hi, tormented by visions of a bearded, motorcycle-riding, grenade-toting, cigar-chomping demon out of hell sees that vision materialize out of hellfire in the form of bounty hunter Leonard Smalls (professional boxer Randall Cobb). A little economics lesson is brought into the film when Smalls introduces himself to Mr. Arizona, informing him that he will find his son, but he won’t accept any reward that’s less than the market price for babies.

The film as a whole, while in the guise of a comedy with its whacky dialogue and outrageous characters, really seems like it has something to say about the American Dream and the uncertain appeal of modern family life. Told from Hi’s perspective with plentiful voiceover from Nic Cage, the whole thing can be viewed as a kind of test of character. Having found temporary bliss in his marriage, the whole kidnapping ordeal causes him to fall into familiar patterns of behavior out of desperation and confusion. His lawless past manifests in cartoonish fashion, depicted as a Hells Angel and two outlaws who literally crawled out of the bowels of the earth. Countering Hi’s lawless past are Dot and Glen (Sam McMurray), the “successful” American couple, who have raised a pack of rabid hyenas and claim to have a happy family. In this way, Hi mentally bounces around from one anxiety-inducing situation to the next.

All of this build-up is brought to a head in a brilliant sequence where Hi—out of a job because he punched Glen, his boss, in the face when the father of five brought up the potential of a wife-swap—attempts to rob a convenience store while Ed and Nathan Jr. wait in the car. With pantyhose covering his face, Hi waves his unloaded gun at the clerk, who alerts the authorities and eventually begins unloading a revolver in Hi’s direction. Ed, irate at her husband’s relapse into crime, drives off without him. A pack of dogs chases Hi, who flees on foot, police officers shoot at him in a grocery store, and the banjo-and-yodel soundtrack gives the comic scene a fun buoyancy. When Ed finally retrieves Hi, he begins to explain himself from the passenger seat, but she socks him square in the jaw (Cage goes cross-eyed for comedic effect). As they drive away, the Huggies that had been the reason for the trip in the first place are scooped up from the street where Hi had dropped them during the pursuit. It’s an all-around brilliantly executed scene.

The Coens have done serious and silly and mixtures of the two for their entire career, Raising Arizona is when they first hit upon their jackpot formula. If it has a fault it is that it peaks too early and its more nuanced scenes are overshadowed by the chase sequence. At some indeterminate point midway, the film’s humor kind of peters out, and it must follow through on its premise to some kind of logical conclusion. It doesn’t have the measured pacing that has made The Big Lebowski and Fargo such cult classics, but it comes as close to sentimentalism as any Coen brothers film, ending with a sappy dream sequence in which Hi imagines that he and Ed have grown old and are being visited by their grandchildren. There are a lot of different elements that make Raising Arizona a great film, but I think more than anything it stands out as a smartly made comedy, which is a sorely lacking genre even 30+ years later.