“We accept the reality of the world with which we’re presented. It’s as simple as that.”

The Truman Show is built on top of a fascinating high concept, serviceably worked out on paper but executed with great verve, succeeding on the back of Peter Weir’s direction and Jim Carrey’s star power.

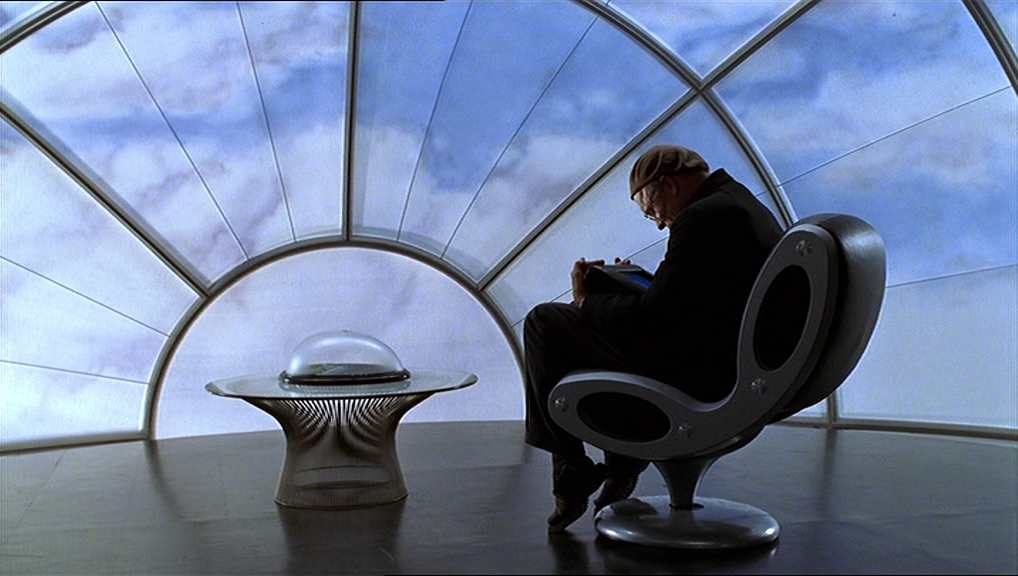

Carrey plays Truman Burbank, the unwitting main character of a lifelong Kafkaesque soap opera. Since his birth, his entire existence has been broadcast to the world, using some five thousand hidden cameras spread all across the city-sized terrarium called Sea Haven. Masterminded by Christof (Ed Harris), the experimental reality television program has become the most popular show in the world, with millions of dullards sitting enthralled by the everyman’s mundane existence. He eats, he sleeps, he sells insurance, he puts up with a wife (Laura Linney) who seems more interested in recommending household products with a smile than being his soul mate and relies on the reassurances of a best friend (Noah Emmerich) whose dialogue is fed to him through an earpiece. He really wants travel the world—specifically to track down a high school sweetheart (Natascha McElhone) who took pity on him and nearly ruined the entire enterprise half a lifetime ago—but, like James Stewart in It’s a Wonderful Life, he always finds his plans thwarted. He also really wants to be a goofball, to assume the Jim Carrey wild man persona (the film’s most brilliant metatextual flourish), but the rigid structure of his planned life prevents the real Truman from actualizing.

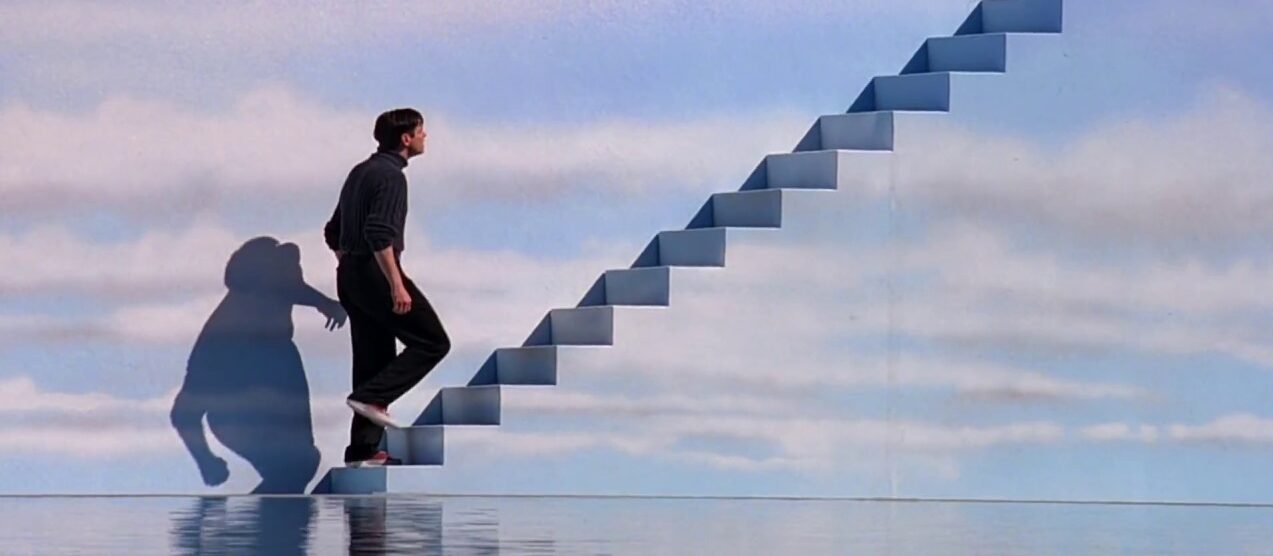

Instead of becoming himself, he suffers from an inchoate longing for a truth he knows is out there, even though the entire world as he knows it has been painstakingly tailored to suit him. This recalls an exchange in The Matrix where Agent Smith explains the downfall of the Paradise Matrix—that humans will chafe against structured utopia devoid of risk, uncertainty, and adventure. When the system finally starts to break down—a movie light works itself loose from the ginormous dome and crashes in the street next to Truman, his car radio picks up the set director’s instructions to the extras, his neighbors’ patterns become too noticeable, the rain system is little too precise—Truman begins to suspect something is fundamentally and gravely wrong with the texture of reality itself, at which point the film moves into its most fruitful portion as Truman begins frantically pushing against the boundaries he has always known.

In Weir’s hands, the numerous holes in Andrew Niccol’s Dickian screenplay are rendered inconsequential as the film speeds through its mildly affecting drama and meta developments with a mixed media presentation, ultimately producing a mesmerizing, peculiarly-structured, life-affirming picture. Analyses of the film extrapolate its rich themes (surveillance, reality television, voyeurism, media addiction, paranoia, existential malaise, Gnosticism) into profound insights about free will, reality, self determination, and the creator-creation relationship. The film itself wisely comes at all of this slantwise, allowing its ideas to percolate instead of dissecting them up there on the screen—a generally sound approach when tackling such material. Another distressing feather in the cap is the fact that our culture has shifted increasingly toward the willing deprivation of privacy and natural identity, meaning The Truman Show is burdened with the weight of being an “increasingly prescient” film.

I tend to agree with Adrian’s Martin’s blistering critique—save for its cathartic denouement (the “true man” literally breaking through the edge of his reality and stepping through a doorway into a life of mystery and uncertainty), much of it feels bit too cold and contrived, and its religious symbolism is somewhat silly—but not to such a degree that I can’t massively enjoy the film as a winsome and intellectually-stimulating mainstream effort. (It’s just that I don’t find it as entrancing as, say, Dark City or Total Recall or Niccol’s previous feature, Gattaca; all films that explore similar thematic territory.) Would that all Hollywood fare was as boldly imagined and thematically interesting as The Truman Show.