“Which would be worse—to live as a monster, or to die as a good man?”

In 2003, Dennis Lehane set out to write a pulpy novel as a send-up to Gothic settings and B movies. Stripping his characters of modern technology and shrouding the entire premise of the book in mystery, his psycho-horror police procedural made for a very compelling read—the first time. Much of the tension is contained in a single twist, so once you’ve read it, subsequent readings don’t measure up to the initial experience. It’s one of those stories where knowing the twist allows you to view the preceding events in a different light, but in my opinion, it’s not nearly as engaging from this perspective. Martin Scorsese’s film version scores enough points on purely cinematic grounds that it doesn’t fall victim to the revelation the way the book does, but it has other faults. Specifically, it tries to elevate its distinctly B movie trappings—insane asylum, steep cliffs, dreary weather, sinister old doctors, mausoleums, nightmares, detectives—into something earnest. But such deliberate craft and theatrics are uncalled for; this is genre fare at its heart, and treating it like high art is a disservice. Teamed up with frequent collaborator Leonardo DiCaprio, Scorsese essentially overshoots the dramatic limits of Lehane’s genre pulp story, and as a result, the committed performances feel more than a little bit campy. It’s a partial misfire, with many positive elements to help it make a case, but it’s not prime Scorsese.

The initial setup and dreamlike atmosphere achieve the aesthetic homage Lehane intended. The visual style harkens back to the old B movies Scorsese grew up on. For narrative purposes, the director (and so, perhaps, Lehane) seems to specifically draw on Sam Fuller’s Shock Corridor, a film about an investigative reporter sneaking himself into an asylum to solve a murder before devolving into madness himself.

Shutter Island is set in 1954, on an isolated island in Boston Harbor. On the island there is a “hospital” where Dr. Cawley (Ben Kingsley) treats the criminally insane, probably through innovative psychoanalysis but possibly via invasive surgery. One of the patients, Rachel Solando (Emily Mortimer/Patricia Clarkson) has inexplicably escaped from her locked and barred cell, and U.S. Marshals Teddy Daniels (DiCaprio) and Chuck Aule (Mark Ruffalo) are called in to investigate. As their boat drifts out of the fog, detached from any specific point of origin, the Marshals, who have never worked together before, develop a quick rapport over cigarettes. Their task seems simple enough, and finite—find a missing woman on an island from which she cannot escape—but the situation quickly gains some depth; or at least, the illusion of it.

Solando, a patient brought to the island after drowning her three children then arranging them at the kitchen table, remains as an object of pursuit but ultimately a secondary one. Teddy’s concerns are not as straightforward as finding the escapee. During a round of patient interviews, he repeatedly asks if anyone knows of a fellow patient named Andrew Laeddis. In a dream of his dead wife, Dolores (Michelle Williams), he had been told that Laeddis was on the island. We are left in the dark, as is Chuck, until Teddy confesses that he requested the assignment because he thought Laeddis, the arsonist responsible for his wife’s death, would be on the island. He believes that Laeddis is in Ward C, one of the two areas the Marshals are restricted from accessing, the other being the lighthouse.

There are quite a few sequences interspersed in the main story where we enter Teddy’s head in order to flesh out his psyche. There are two primary threads that his mind plays with. One is his participation in the liberation of Dachau, during which Germans POWs were killed by U.S. troops. This episode comes back to him in waking visions during migraine attacks. The grisly imagery of dying soldiers pairs well with the discussions Teddy has with a number of supporting characters on the subject of violence. Dr. Naehring (Max von Sydow), a German doctor, immediately marks the Marshals as men of violence, describing their childhood tendencies to them and remarking on the defense mechanisms Teddy employs in conversation.

Did you know that the word ‘trauma’ comes from the Greek for ‘wound’? Hmm? And what is the German word for ‘dream’? Traum. Ein Traum. Wounds can create monsters, and you, you are wounded, Marshal. And wouldn’t you agree, when you see a monster, you… you must stop it?

In a later scene, after losing track of Chuck in the wake of a hurricane storm, Teddy is escorted across the island by the Warden, played by Ted Levine. Though he’s done extensive work in film and television, Levine’s most prominent role is still his portrayal of Buffalo Bill in Silence of the Lambs. So when he launches into an extended, terrifying discussion on the nature of violence, his sinister demeanor has an even sharper edge to it.

Warden: Did you enjoy God’s latest gift?

Teddy: What?

W: God’s gift. The violence… when I came downstairs in my home, and I saw that tree in my living room, it reached out for me… a divine hand. God loves violence.

T: I… I hadn’t noticed.

W: Sure you have. Why else would there be so much of it? It’s in us. It’s what we are. We wage war, we burn sacrifices, and pillage and plunder and tear at the flesh of our brothers. And why? Because God gave us violence to wage in his honor.

T: I thought God gave us moral order.

W: There’s no moral order as pure as this storm. There’s no moral order at all. There’s just this—can my violence conquer yours?

T: I’m not violent.

W: Yes, you are. You’re as violent as they come. I know this because I’m as violent as they come. If the constraints of society were lifted, and I was all that stood between you and a meal, you would crack my skull with a rock and eat my meaty parts… wouldn’t ya? Cawley thinks you’re harmless and that you can be controlled, but I know different.

T: You don’t know me.

W: Oh, but I do. Oh, I know you. We’ve known each other for centuries… If I was to sink my teeth into your eye right now, would you be able to stop me before I blinded you?

T: Give it a try.

W: That’s the spirit!

These interactions are the highlights of the film for me. Give skilled actors good lines and let ‘em go at it.

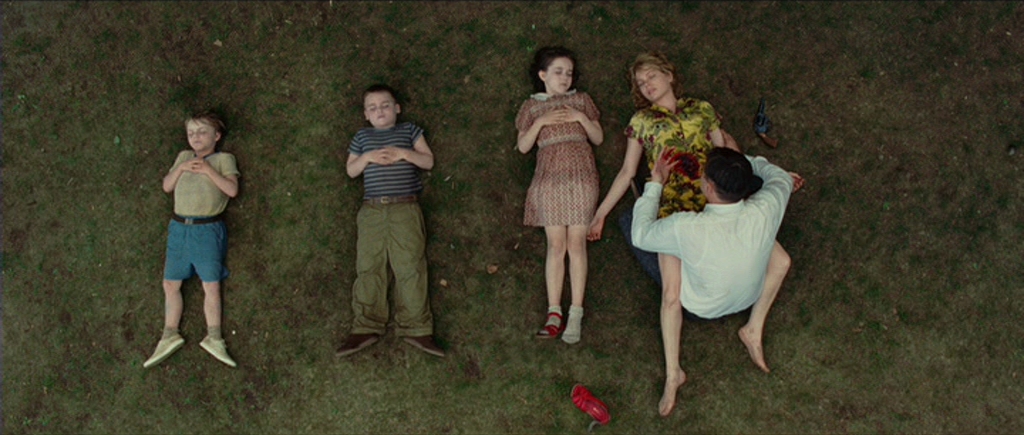

The second way we enter Teddy’s head is via dream sequence. In his dreams, Dolores gives him clues to help him solve the mystery. I think these scenes are less successful, although they’re necessary to give Dolores an onscreen presence so that the resolution lands well. They don’t feel as polished or integrated as they should, but there’s one in particular that doesn’t work well, even though it is presented as a centerpiece of the film. In Teddy’s dream, the couple embraces as blood spills down her dress and the house turns to ash around them. It’s a visually haunting scene, bolstered by the evocative pulse of Max Richter’s “On the Nature of Daylight”—a simple yet sublime piece of music that is at-risk of overexposure. The problem is that Shutter Island is not a serious movie that deserves this kind of attempt at transcendence/catharsis. The appeal of Shutter Island is its style and sleight of hand, not its drama—and so this overwrought theatrical moment is out of tune with the rest of the film. (I hate to say this, though, because I actually think that this scene is superbly well-crafted. Maybe brilliant, even; but only in isolation. The music swells just as Dolores herself turns to ash and crumbles in Teddy’s arms. Truly memorable stuff. But it simply doesn’t jibe with the general tone of the film.)

Shutter Island never spoils its eerie build-up by actually resorting to the excessive violence it talks about. It works its way under your skin by giving you the sense that things are slightly-off, and carries that sense of uneasy foreboding through to the film’s conclusion, even adding a nice little wrinkle at the end that is not present in the novel. Although the narrative itself doesn’t blow me away once all the pieces are revealed, the way that Scorsese guides us through waves of suspense with the practiced hand of an illusionist makes Shutter Island worth your time. Of course, much of the suspense hinges on the performance of DiCaprio, who is certainly giving it his all, but, like I said, doing so in a film which doesn’t really need it; and so it comes off as overdone. Levine, Kingsley, and von Sydow, along with Patricia Clarkson as a hallucination that Teddy encounters in a cave, are able to straddle a fine line between dramatic and ironic. They take delight in delivering the semi-serious lines without revealing how seriously they view their own performances.

To get the most out of the film, it’s probably better to have read the book. I say that because without knowledge of the big reveal (which I’ve tried to avoid pointing to here, but which isn’t that difficult to puzzle out), you’ll find yourself invested in details that don’t necessarily cohere into something grand, that Scorsese employs exclusively to build the mood. I think, rather, that most enjoyment can be gotten from the film by taking account of its specifically filmic details—the lighting, the wardrobe, the soundtrack. The reveal only worked for me the first time I read the book, but Scorsese’s film is pretty good even if you’ve already seen it—maybe even better. But the film kneecaps itself by trying to reach beyond its genre limits. It asks to be taken seriously when it would work better as a supreme B movie.