“You are fearless in a way that I will never know.”

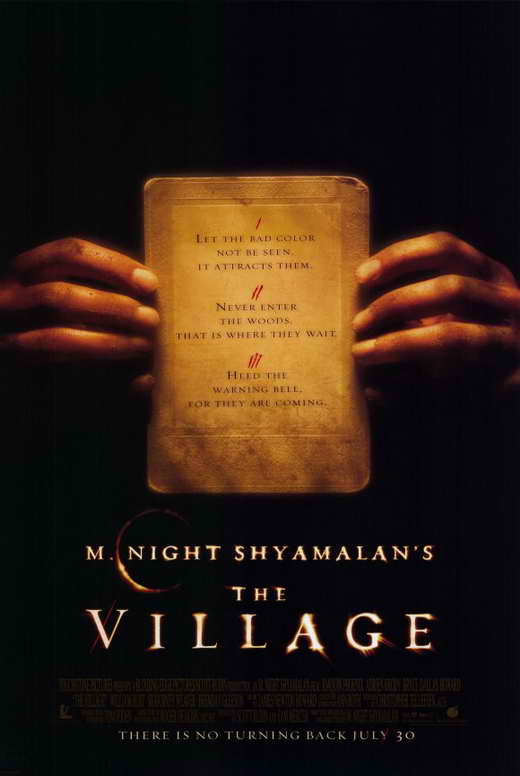

My wife likes to do this thing when we sit down to pick a movie where she requests that I choose something she will like in terms of genre, era, tone, pace, and most importantly, narrative closure (she doesn’t tolerate ambiguity very well). This task is manageable, maybe even easy—but she adds another criteria that makes it nigh impossible: I must choose a film that I’ve never seen before. As you might surmise, this puts me in a bit of a pickle. Quite frequently she will walk away dissatisfied, but I’ve honed my movie-picking skills enough that I’d say I bat at least .500. In recent months, M. Night Shyamalan has really helped me improve my average because he writes the kind of movies she tends to jibe with. When movie night rolled around and memories of Signs were still tickling our brains, we settled on The Village after a few moments of otherwise fruitless pecking.

Now, if you know Shyamalan, even if just by reputation, you’re aware of his penchant for “the twist.” Beginning with The Sixth Sense, he made a string of projects that had big rug-tugging moments built into them. This meant that avoiding spoilers for each new project was paramount else you would have a lesser experience when you finally saw it. Although audiences eventually grew weary of the schtick—leading to a slump from which the director has only recently recovered—The Village arrived before opinions had soured. Indeed, for many it was the final straw. In any case, unlike The Sixth Sense, I went into it without any preconceived notions. Most importantly, while I knew there was a twist, I had no idea from whence it would come. I was genuinely excited to have my mind toyed with, even if I would find it a bit tacky in hindsight. Imagine my dismay, when, five minutes into the film my wife says, “Is this the one where…?” and proceeds to spoil the twist. My goodness, woman. I bought you that fancy engagement ring and this is how you repay me? Thankfully, she only knew half of it. Even better, the screenplay, direction, and performances are strong enough that the movie is enjoyable even with a small list of spoilers in the back pocket.

The Village is set in the late 19th century in the backwoods of Pennsylvania where an isolated community of puritans lives in seclusion. The forest surrounding their little town is home to Those We Do Not Speak Of, crimson-clad beasts with six inch claws that prowl the perimeter in the night and are attracted to the color red. The villagers live in constant fear of the monsters but the elders—played by William Hurt, Sigourney Weaver, Brendan Gleeson, Cherry Jones and others—assure the children that a truce has been made: if the villagers refrain from encroaching on the creatures’ territory, they may live in undisturbed peace. However, it quickly becomes evident that the agreement is fraying at the seams. Boys play games along the torchlit boundary in the middle of the night, the mentally unstable Noah (Adrien Brody) makes excursions into the forbidden zone to pick red berries, and skinned animal carcasses begin mysteriously appearing strewn about the town square.

Against this splendid backdrop Shyamalan sets a standard melodrama, complete with teenage heartbreak, front porch confessions of love, and contrived dramatic turns. The two central characters are Lucius Hunt (Joaquin Phoenix), a taciturn young man who is honest to a fault; and Ivy Waters (Bryce Dallas Howard), a blind but courageous young woman. When they announce their intention to marry, Lucius sustains a wound borne of jealousy and Ivy requests permission to travel through the woods to “the towns” where she plans to obtain the necessary medicines to nurse her beloved back to health.

Playing to his strengths during the buildup, Shyamalan develops a wonderfully menacing atmosphere through the employment of Roger Deakins’ masterful lens, aural trickery, slow motion, long takes, and a haunting violin score from James Newton Howard. The typical Shyamalan set pieces and narrative hijinks are here, but it definitely feels like he’s trying to exert more artistic control than usual. He’s calculated but loose, using silence and subtlety to approach an idyllic romance amidst his far-fetched premise. All of his filmmaking instincts come together in a brilliantly orchestrated scene in which the blind Ivy waits on the porch for her lover to come hide with her as the monsters converge on the village. She stands with her hand extended, unaware that one of the beasts is creeping right up to her and seems poised to strike. When Lucius finally arrives and takes her hand everything coalesces in stunning fashion as the tension is released with slow motion and the pulsing score.

The film slightly falters as it enters its final third and the two-pronged twist is revealed. It’s not so much that one of the twists renders some tense earlier scenes weightless—that’s not terribly uncommon, and at least it was pulse-raising to begin with! Rather, I think, it suffers from the sheer amount of flashback-heavy explanation that is required to contextualize the larger twist. It’s disappointing that, even with a series of flashbacks to subtle clues that we may have picked up along the way, the reveal still comes out of left field. Which is fine, but then leave out the needless repetitions.

Many critics had a field day with The Village. Notably, Roger Ebert, perhaps the most well-known critic of his era, gave the film one out of four stars. He disliked it so much that he retrospectively denigrated Signs, to which he had assigned full marks. The problem is that Ebert doesn’t accept Shyamalan’s premise as presented—within which confines the strange customs, language, and culture make sense—and instead picks apart things that rub against his sensibilities. When it is revealed that the film takes place in modern times, that the isolated community is funded by the inherited estate of one of the elders, he calls it “witless.” It was witless for Shyamalan to predict the logic gaps that would be spotted in his own high concept film and put answers to those objections in the script? Please. He even makes it a meta joke by using himself in a cameo to explain away the issues. In Signs, the aliens that orchestrated a massive kidnapping scheme on earth flew across the galaxy and touched down before determining that they were deathly allergic to a substance that permeates our entire planet. Ebert loved that movie, along with plenty of other high concept popcorn munchers with gaping plot holes, so the contrivance isn’t the issue. However, if you read between the lines it becomes apparent that he found it abhorrent that some people would go to such great lengths to remove themselves from a degenerate society. To reject modernity and embrace a simpler, quieter, more spiritually rich way of life is to leave behind pretty much everything that Ebert (and a whole host of other godless sophisticates) held dear.

Not content to merely contrast this puritanical way of life with the modern rat race governed by a corrupt ruling class, Shyamalan imbues his story with nuance. Is it right to lie to a population for their own good? Is it righteous to avoid pain? At what point must children be allowed to make their own decisions about their futures? Should they ever be let out of Plato’s cave? These questions linger in the background as we are plunged into the rich atmosphere of The Village and witness its tragedy. It’s strikingly prescient, as his vision of societal ills giving rise to isolationism has begun manifesting across the country. But the same evils they fled plague them even in their haven. The well-meaning elders distort the truth in order to protect their community—the medical industry is viewed as corrupt, “the towns” are colored as evil, the myth of Those We Do Not Speak Of is taught from a young age. Is this better than the harms perpetrated by the state? If Shyamalan has a point beyond mere exploration, it is that the innocence of childhood is unsustainable and cannot be protected indefinitely. Children must be formed in such a way that they can confront the iniquities of this world and not crumble. LARPing as pilgrims is fine, but ignoring the evils outside of a man-made bubble only means that those shielded from them will suffer egregiously when the bubble pops.

Obviously, I’m putting a stake in the ground and saying the hate for The Village is unwarranted. I thoroughly enjoyed my time with it even knowing the biggest twist ahead of time. Shyamalan is superb at conjuring tension out of simple setups and practical effects. His writing, while contrived, works within the pocket world he chisels out for himself. The performances from the ensemble cast are uniformly solid, with Howard’s turn as the blind Ivy as a standout. Sure, it lacks replay value because of its twist, but that doesn’t detract from the thrills you will experience the first time you see it.