“You say too many prayers for an innocent man.”

Shortly after I graduated college, my brother and I walked the ~2190 miles that constitute the Appalachian Trail. It was humbling, grueling, and unforgettable. Early on, we hiked in snow and slipped around on ice, and once awakened to find our sweaty clothes frozen stiff and our precious water supply solidified. Later, in the hot and humid climate of the East coast summer, I spent a day and a half suffering from dehydration (shout out to powdered Pedialyte—you the real MVP) and my stink seemed to attract every mosquito in the state of Maine. By the end of our travels walking twenty-five miles in a day was a common occurrence. Thirty mile days were achieved a handful of times. Finishing the AT took perseverance and willpower. It’s a challenge that most people can’t fathom taking on. And yet throughout the journey I was well fed and (usually) sufficiently hydrated. I occasionally took hot baths and shaved my face and cleaned my ears. I slept in real beds sometimes, including once in our aunt’s basement when she bailed us out during a snowstorm in Tennessee. The Appalachian Trail is difficult, but obviously doable, considering how many people have completed the trek.

Peter Weir’s The Way Back chronicles a much more arduous journey than the one my brother and I undertook. For starters, it was about twice as long. It begins in the hypothermic Siberian winter (much worse than the early spring of Georgia), stumbles its way through the mirage-inducing heat of the Gobi desert, and passes through the snow-capped Himalayas. Oh, and the men who initially begin this journey do so as an alternative to working themselves to death in a Soviet Gulag. They begin their hike with only a small accumulation of rotting food and the clothing on their backs. Some even have boots. One of them dies from severe cold, several more succumb to severe heat. On second thought, maybe the common ground between our exploits and the harrowing travels of the prison camp escapees doesn’t amount to all that much.

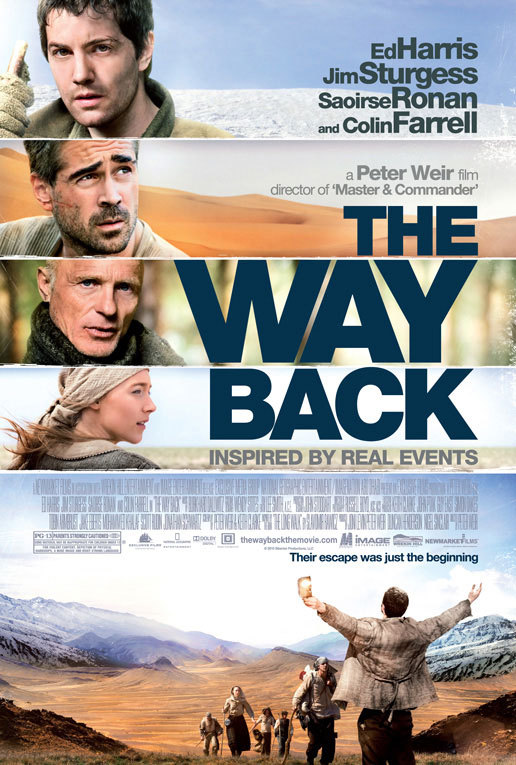

All of our principle characters save one can be found in the work camp in Siberia. Due to the endless manual labor, nasty conditions, food shortages, and rampant disease, the prisoners have very short life expectancies. A young Polish officer named Janusz (Jim Sturgess) is sent there after the invading Soviets torture his wife and force her to give false testimony against him. He’s quickly befriended by Khabarov (Mark Strong), watches in horror as Valka (Colin Farrell) stabs a man over a gambling disagreement, and gets sent to work in the mines with “Mister” Smith (Ed Harris). The group is rounded out by Zoran (Dragoș Bucur), Tomasz (Alexandru Potocean), Andrejs (Gustaf Skarsgård), and Kazik (Sebastian Urzendowsky). Realizing that they’d rather risk their lives in the wilderness than be gradually worn down by disease and famine in the Gulag, the unlikely fellowship of Poles, Americans, Russians, Yugoslavians, and Latvians makes a break during a blizzard and begins the impossible walk to freedom.

There are two complaints that critics consistently raise against The Way Back. I think both are legitimate points but I don’t trace them back to the same root and thus don’t find them to detract from the experience in the same way. The first issue is that there isn’t enough internal conflict amongst the men once they escape from the prison. Valka is a cutthroat scoundrel and is perceived as a loose cannon, but he never actually steps out of line. The worst he does is disobey orders to skirt around a town, instead sneaking in to steal food for himself and his companions. The others have various backgrounds (cooking, sketching, pastoral ministry) that are woven into the minimal conversation amongst the group but don’t create any real tension. When they discover that a young Polish girl named Irena (Saoirse Ronan) is following them, they allow her to join their party; none of the men make an advance at her and so there’s no cause for competition or masculine posturing.

These are areas that screenplays typically use to generate drama and, because The Way Back doesn’t, critics found it lacking. But to call out the dearth of interpersonal conflict is to ignore the wider encounter. Sure, the escaped prisoners are always wary of encountering enemy soldiers or getting reported by civilians, but this is not primarily a man vs. man encounter, it’s man vs. nature. The bad guys are the sun, snow, rocks, mountains, bugs. So while it’s true that the men don’t speak an awful lot—this is actually pointed out explicitly when the relatively spry Irena bounces between the men, learning about their lives and relaying those details to the others—that’s precisely the point. In fact, these troopers engage in extraneous banter way more than anyone would in their shoes. In my view, what’s missing here is not interpersonal conflict. I prefer the loyal brotherhood angle that Weir uses. What’s actually lacking is a clear articulation of the internal struggles. Weir prefers to hint and imply rather than state outright in this regard.

The other common gripe is that the film feels too episodic. First it’s the prison camp, then the snowy mountains, then the desert, then the Himalayas. As I said, the conflict is almost always generated between our travelers and their inhospitable environment. Consider the face shields they make from birch bark to protect against the blizzard; the sandstorms, sunstroke and swollen feet suffered in the desert. Not to mention the regular scarcity of food and water that leads to Janusz briefly abandoning the others in search of a lake. During his journey he gnaws on hunks of bark to satisfy his hunger. As the travelers follow a route from Siberia to India they encounter logical environmental challenges that come with each new territory. This episodic complaint, then, is akin to the earlier one: the natural obstacles are insufficiently entertaining. Which is a matter of taste, and in any case, it is really more of an issue with Slawomir Rawicz’s disputed account than with Weir’s adaptation. The Polish POW’s ghost-written memoir was titled The Long Walk, and its very title seems to address both complaints equally. This is not about entertainment or WWII politics or clashing worldviews or whatever. It’s about physical and mental endurance, mettle and grit, the will to live in spite of extreme hardship. Even with a meager grasp of the film’s framework one should understand that to do the story justice all but requires both of the things that critics disliked.

And anyway, to hate on The Way Back for those things is to neglect an abundance of superb contributions from cast and crew. Though nine main characters is perhaps too many for the story’s requirements, the performances are top notch. At first, Sturgess appears underwhelming as a leader but that is intentional. He has the spirit but lacks the skills, relying on pluck and determination and the ability to use the sun as a compass to see him through. Covered in tattoos and bearing a fake tooth, Farrell proves a splendid chewer of scenery and clearly takes delight in twirling his knife (although his giddy performance slightly overwhelms the serious tone). Ed Harris plays a familiar role that he handles with ease. Ronan, who was all of sixteen at the time, handles herself with poise amongst the more experienced cast members. The others, though given less material, all have at least one moment apiece in which the focus is entirely on their character.

Weir deftly takes a backseat, minimizing himself in favor of the environments and the cast. He gracefully handles the deaths of three characters by allowing the performers to carry the scenes. No swells of music to tug at heartstrings, no memorable last words, no melodrama. Just the raw emotion generated by the cast, aided by the sensational work from the makeup team (which received an Oscar nom) to emphasize the brutal physical realities of their ordeal.

My main contention, which I alluded to earlier, is that the psychological burden that gradually beats these men into the ground is given too little emphasis. The physical elements are expertly realized, from threadbare costumes and accumulated grime to blisters, pustules, and bleeding feet, but the inner conflicts are seldom verbalized. The most obvious counterexample is when Andrejs, a former priest, stands in the ruins of a temple and confesses that he had killed a man. These moments are rare, though, and I feel that exposing the inner turmoil would have allowed richer characterizations without necessitating conflict within the group.

The Way Back is a solid film from a veteran director. It’s a grand technical achievement with an abundance of breathtaking and elaborate shots captured on location. An epic in the mold of David Lean. The gruelling account of survival is less engaging than it could be, holding its characters at an odd distance, but Weir orchestrates everything else with such skill that his film is worth watching despite its shortcomings.