“But the life we enjoy is very much worth the sacrifice.”

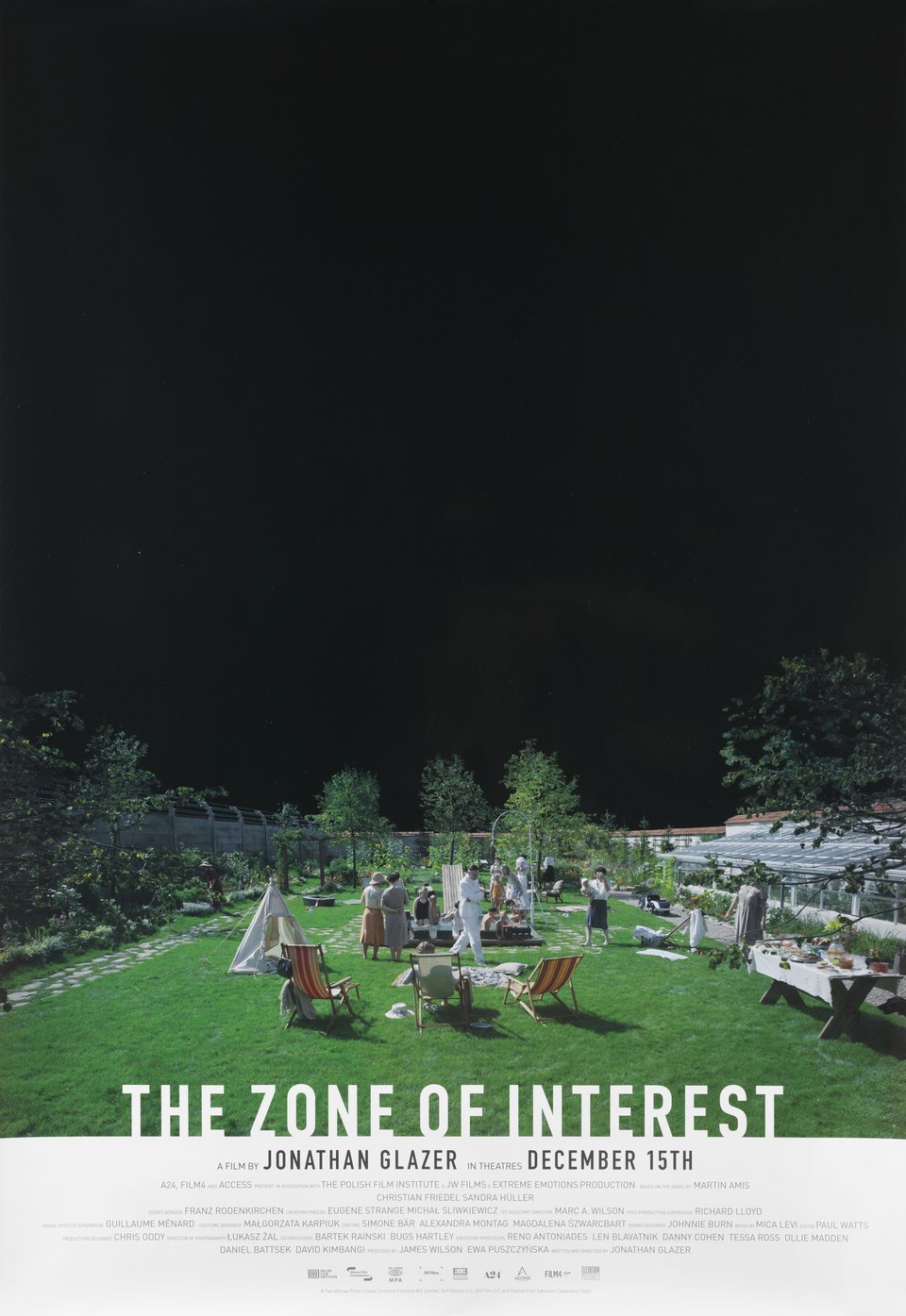

It would be foolish to criticize Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest against its own criteria because it achieves exactly what it sets out to do, which is to observe the idyllic lives of Rudolf Höss (Christian Friedel), the commandant of Auschwitz, his wife (Sandra Hüller), and their children as they go about their daily routines within earshot of the concentration camp’s dark operations. To depict the banality of evil, as Hannah Arendt phrased it.

Using an aggressively dull and dispassionate and choppy style, Glazer emphasizes the family’s domestic patterns, fixating on and finding psychological tension within the mundane details of picnicking and fishing and swimming and gardening and the reading of bedtime stories in much the same way as Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, drawing viewers into a voyeuristic study of characters unaware or willfully ignorant of the grave evil encroaching on their lives.

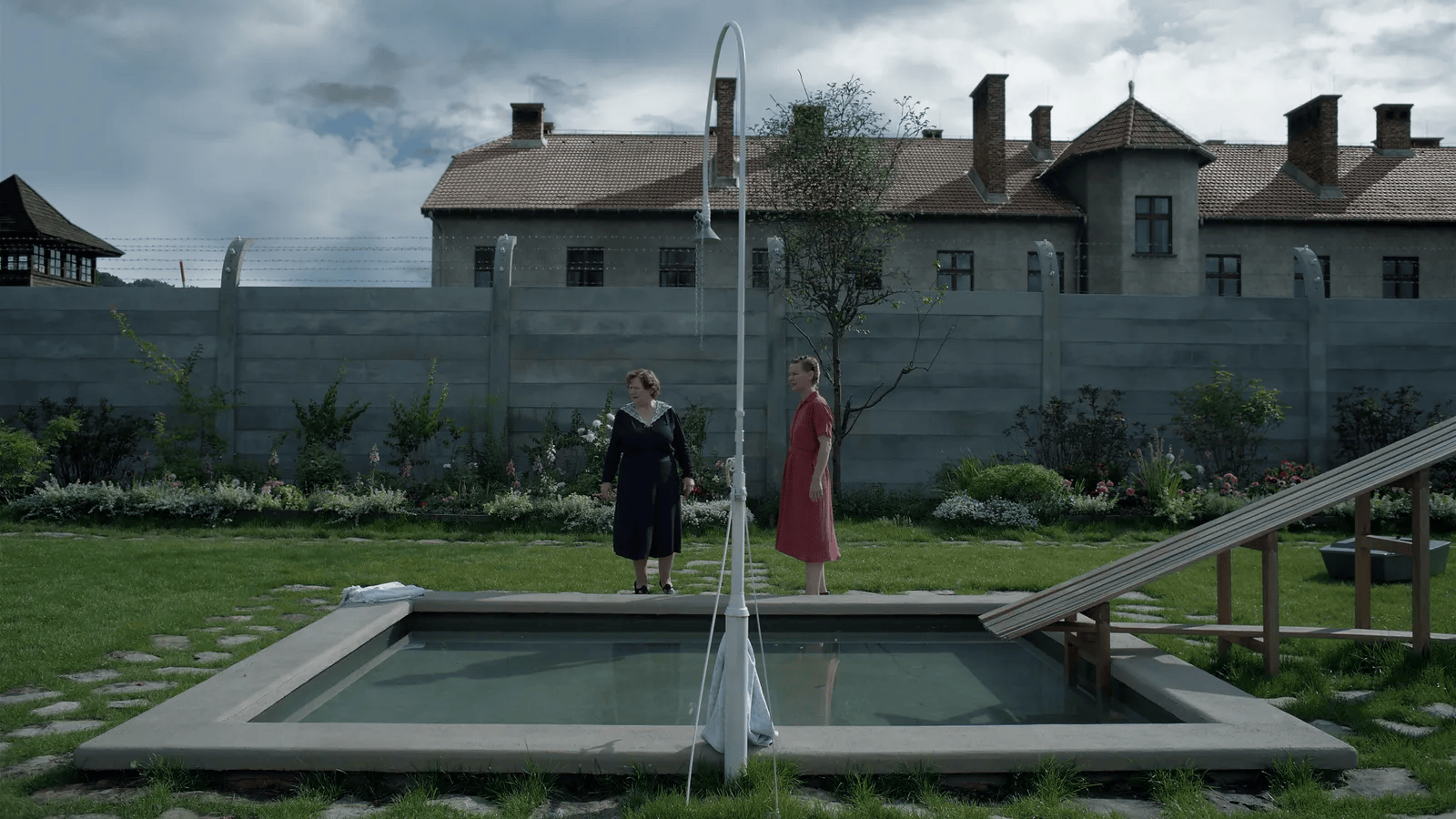

It’s executed with undeniable skill and selective artfulness. Convincing portrayals are shot with a clinical disinterest, with a staggering sound design (Johnnie Burn) that allows the filmmaker to totally forgo visually depicting anything that might shock the viewer (just as the characters keep these things out of mind), but giving constant reminders of the horrors occurring just outside the walled-off confines of their otherwise blissful homestead—screams, gunshots, and the low roar of the furnace, just outside of the camera’s frame, implying complicity without explicitly acknowledging the crimes themselves. Even the trains chugging along the horizon aren’t harbingers of death unless you know them to be so. From a certain perspective one might see the film itself as ignoring the atrocities it is so careful to not actually show, as without a pre-existing knowledge one might be completely lost here.

Low-key drama does emerge when Höss is promoted and forced to move but his wife wants to stay at their current home with the children, but otherwise this is a sedate, detached examination of the life of a fairly high-ranking Nazi official, who definitely knew the sins being carried out under his command but kept his distance from them. He discusses logistics of a new crematorium and makes the death factory much more efficient, and is largely responisble for the camp’s name lingering in the cultural consciousness, but the closest he comes to the sausage-making of the genocide itself is when he finds a discarded body part floating downriver from the plant where he is playing with his kids. His wife tries on a fur coat and lipstick that came from somewhere… surely she understands, but keeps that understanding submerged several fathoms deep. Only when she is caught in a fit of rage does she reveal her basic wickedness when she lashes out at her servant, asserting that her husband could have the girl’s ashes spread across the fields. But otherwise they just seem so normal, with many of the same passions and obligations and concerns that we do! They’re a little self-centered, but they don’t spew Nazi ideologies. Hence, the banality of evil.

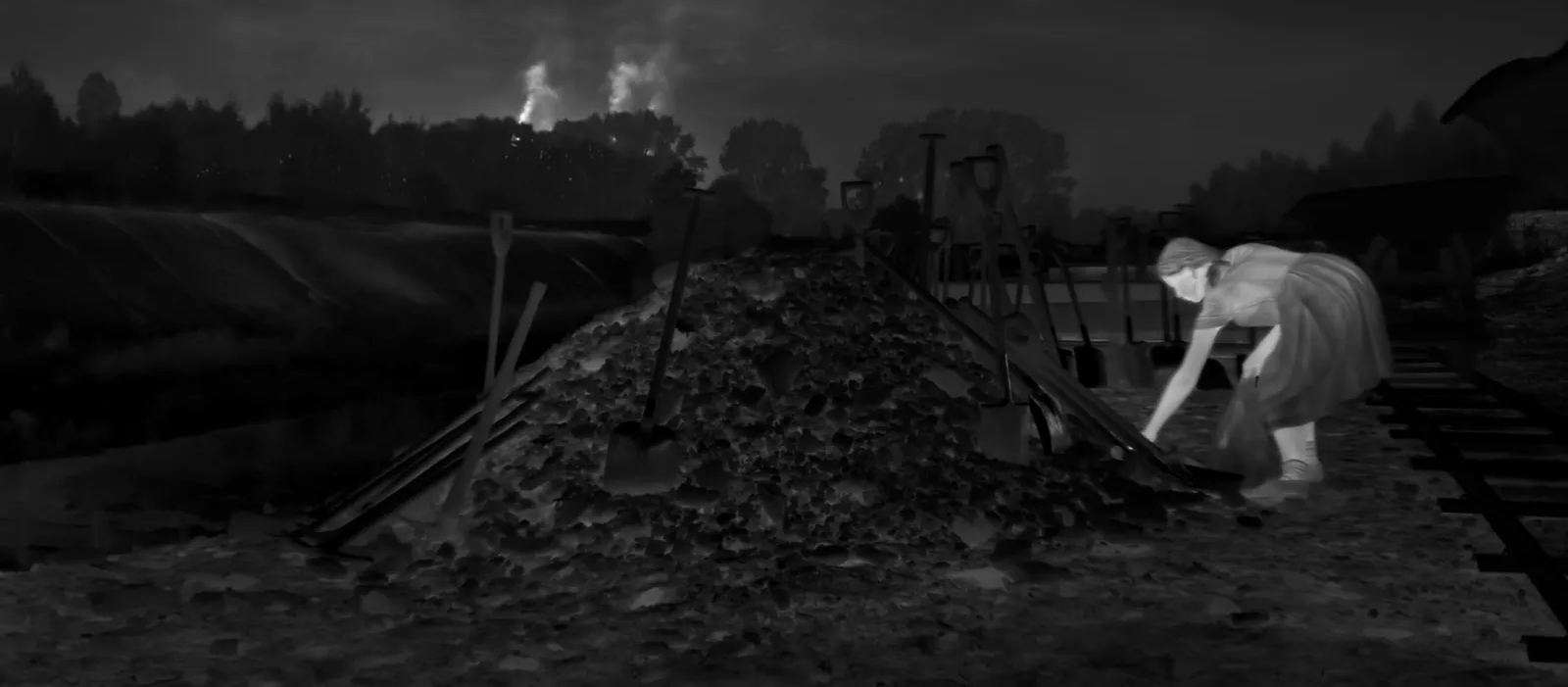

Just as he did with Under the Skin, though less strange and surreal, Glazer uses aesthetically audacious digressions to segment his main narrative. In this case he uses a thermal camera to depict a young Polish girl (Julia Polaczek) who ventures to the prisoners’ work sites in the dark of night to hide fruit for them. These scenes are set to the father reading ‘Hansel and Gretel’ to his children, giving the film an aura of a dark fairytale and dissipating any sense that the film was merely an exercise in laborious irony. Eleswhere, there’s an ambient droning noise that occasionally unnerves, and at one point the frame just fades to bright red out of nowhere like an angry flare-up. A quick jump ahead to view a cleaning crew wiping and vacuuming in a modern day Holocaust museum is an eerie touch.

My only complaint, then, is one of conception and reception: to me, it is clear that The Zone of Interest was created, first and foremost, to be written about and discussed, to provide an impetus for people to lay out their own moral systems and whatnot. The film itself does not provide moral dictation—which is refreshing—but its quotidian non-story and intentionally off-putting style bluntly prompt the viewer to ponder things that don’t necessarily require an intensely anti-artistic slog to begin pondering. Perhaps its most pertinent and probing suggestion is that Holocaust prestige films should be received with disgust and not excitement (echoing the discussion that hovered around Schindler’s List). In that light, it feels a little bit like Poor Things, in that its incessant unpleasantness seems to be a challenge to the critical establishment who seem mostly unwilling to call a spade a spade. Some have responded thoughtfully to the film’s anti-artistic aesthetic, some have blindly extolled it because it appears smart and sophisticated and serious—but many have simply used the opportunity to claim the moral high ground or connect it to their pet social issue. They all, of course, would have spoken truth to power if they’d been alive then. Of course.