“You sure are one lost dude, aren’t ya?”

If you’ve ever wanted to see Jeff Bridges eat ice cream like a lunatic, sticking the scoop of pistachio so far into his mouth that he must hold the very tip of the cone with just thumb and forefinger; if you’ve ever wanted to see Jeff Bridges casually lie prone to suck lakewater directly from the surface while Clint Eastwood pops his shoulder back into socket in the background; if you’ve ever wanted to see Jeff Bridges pretend he has a wooden leg while in the process of stealing a repossessed Chevy Task-Force from a used car lot; if you’ve ever wanted to see Jeff Bridges disguise himself as a hooker to distract a Western Union security guard; or if you’ve ever wanted to see Jeff Bridges have a stroke—then Thunderbolt and Lightfoot is the movie for you.

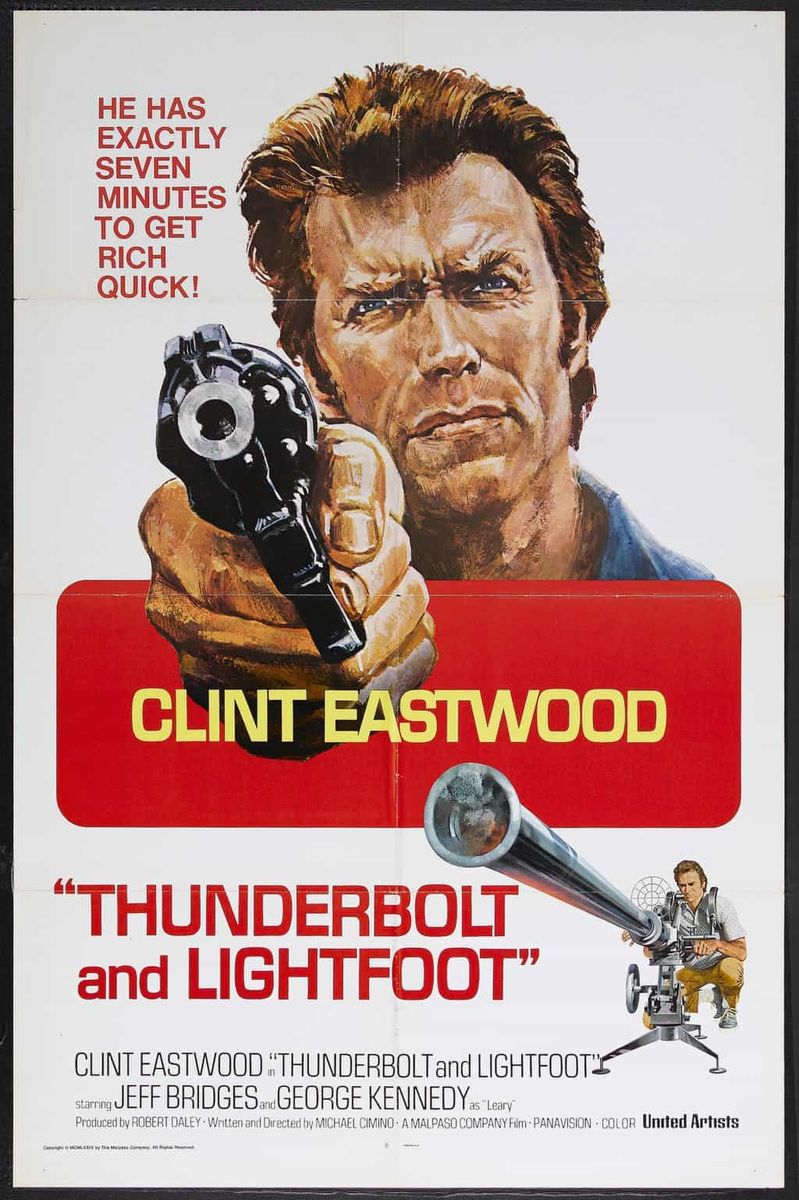

Of course, all of those things are just quirky asides in Michael Cimino’s gorgeously shot, narratively meandering road movie–cum–crime caper. And none of them even qualify as the weirdest bit! Such an honor might go to a number of other extraneous delights: Red (George Kennedy) hitching a ride in Goody’s (Geoffrey Lewis) undersized, doorless ice cream truck only to get so annoyed with an astute child that he uses a choice four-letter world to forcefully tell the boy to make love to a duck; or maybe the grouchy gas station attendant who responds to Lightfoot’s (Bridges) “How’s business?” with a vapid rant about the mirage of the American economy; or maybe Thunderbolt (Eastwood) and Red using an anti-tank cannon to blast their way into a high-security vault.

In this business, you’re always one step away from bankruptcy. Funny money, credit, speculation… Somewhere in this country’s a little ol’ lady with $79.25. The five cents is a buffalo nickel… If she cashes in her investment, whole thing’ll collapse. General Motors, the Pentagon, the two-party system and the whole shebang… We’re all running downhill. Gotta’ keep running faster or we’ll fall down.

But if we absolutely must decide upon the most comically absurd pleasure offered by Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, the choice is a no-brainer. After Thunderbolt and Lightfoot have become fast friends—some mixture of pure male friendship and a father-son relationship, with vague hints of possible homosexual urges—the pair find themselves on the run from Thunderbolt’s former associates, Red and Goody. They’ve momentarily evaded their pursuers by taking a detour through a rocky valley which has done a number on their car. Stranded on the side of the road, they desperately try to thumb down every vehicle that passes. Finally, one stops. They hoot and holler and catch up to the stopped car, offering words of gratitude and flinging themselves into the backseat. Neither can ride shotgun because, of course, the exhaust-huffing motorist (Bill McKinney) that has offered them a ride has a caged raccoon in the passenger seat. He slurredly rambles amidst the haze of rerouted fumes and soon rolls the car into an abandoned field. Dazed and discombobulated, our protagonists stumble from the wreckage only to witness the madman releasing a herd of white rabbits from his trunk. He then begins wildly shooting at them from point blank range with a shotgun.

If these idiosyncrasies weren’t enough to catch one’s interest, consider that Thunderbolt and Lightfoot is a heist movie that shambles along for nearly an hour before it hints that it might contain a heist. It’s so nonchalant about its central plot point that it’s barely worth recounting Lightfoot’s proposal to replicate Thunderbolt’s legendary crime and its failed execution. In summary, they knock off the same company using the same technique with the same crew. The only difference is that their electrician perished in the opening scene when Lightfoot ran him over with his stolen Task-Force. Lightfoot, whose skills do not include technical wizardry, must don a wig and lipstick to accomplish the same objective in a different manner.

But again, the mechanics of the heist are almost an afterthought. Instead of focusing on that, Cimino is more concerned with sketching out a climate of existential despair tinged with melancholy and gallows humor; a portrait of a dying American dream. The reason Thunderbolt’s old pals are after him at the beginning of the film is that he’s the only one who knows where the money from their first heist is stashed: behind the blackboard of a little one-room schoolhouse in Warsaw, Montana. He and Lightfoot try to retrieve it, but find that a modern school has been built in its place. In the film’s concluding sequence, they stumble upon the old building. It’s been picked up and placed along a highway as a tourist attraction for passing travelers. A plaque in front of it reads: “The one-room schoolhouse evokes a vision of a vanished America.” If the Land of Opportunity ever held a future for free-spirited outsiders, it appears entirely hostile to them now, a sentiment echoed by the film’s pessimistic coda.

To hone in on Cimino’s strand of warped Americana, the first hour of the film is spent drifting through back channels and forgotten little towns; carjacking, picking up women, telling stories, allowing the elder statesman and the young gun to discover kindred spirits in one another. There’s initially a distinction between Eastwood’s taciturn war hero turned robber turned country preacher and Bridges’ brightly attired, off-kilter dropout; but this contrast blurs as parallels between the two become apparent. They’re both desperados without a home in modern society, and yet when they try to carve out a niche for themselves outside of it they find that the frontier has been overtaken entirely by cookie cutter suburbia. There’s just no place for the charming outlaw anymore; civilization has snuffed out everything it couldn’t tame.

Thunderbolt and Lightfoot slots right in there next to other existential post-hippie road movies like Easy Rider and Two-Lane Blacktop, films that buck convention, color outside the lines, and allow their characters to drift through a world full of mystery. Eastwood was looking to make a film in this vein circa 1973 when his agent passed him Cimino’s spec script. He initially intended to direct the film himself, but became so impressed with Cimino (who had co-written Eastwood’s Magnum Force with John Milius) that he decided to throw his support behind the aspiring filmmaker. Cimino’s career is something of a mixed bag, but the charm of his debut is undeniable.