“A thousand years from now when school kids study about America, they’re going to learn about three things—the Constitution, rock ‘n’ roll, and baseball.”

Frequency is simultaneously a heartfelt reminiscence about loss and the passage of time, a pot-boiler about a serial killer, and a science fiction head scratcher. That it manages to land on two feet is some sort of miracle. Its sci-fi elements are handwavy, explained by mentions of string theory and an occurrence of aurora borealis, and only set up the framework for the film’s central plot device. But the film is not about that, really. It’s about baseball, relationships, America, and memory. Its ending is quite contrived, and tries to wrap things up too neatly, but there’s something universally compelling about humanity’s desire to conquer time that makes it enjoyable and wholesome.

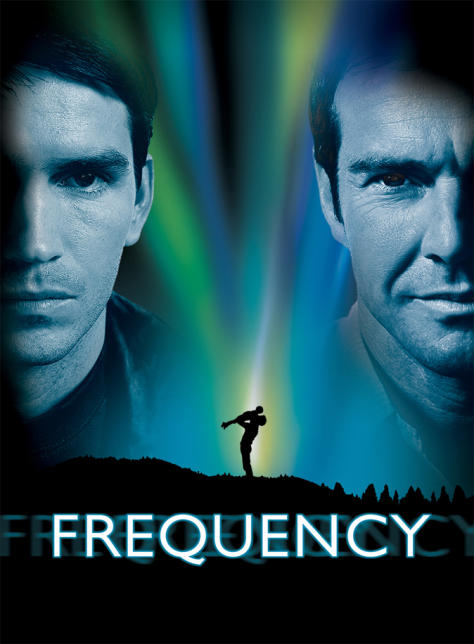

The story follows John Sullivan (Jim Caviezel), a police officer who finds himself engaged in an interesting conversation one evening. He is speaking with a stranger on an old ham radio that had been locked in a box since his father’s death in a warehouse fire thirty years ago. Their ongoing conversation becomes strange and unsettling, and it is only after John predicts the events of the 1969 World Series that Frank Sullivan (Dennis Quaid) accepts the fact that he is somehow talking to his son thirty years in the future. The 1969 World Series features throughout the film as a touchstone. It convinces Frank; but it also is used in flashback, as we see young John (Daniel Hensen) watching the game with his friends, and to convince Sergeant Satch (Andre Braugher) of the truthfulness of Frank’s story.

The establishment of the new relationship between Frank and John after thirty years is the highlight of the film. That they are separated physically makes the achievement even greater, and the believable bond between them owes its success to the strong script and the acting of Quaid and Caviezel. There are many films where extraordinary situations are handled in incredibly stupid ways by the characters, but Frequency handles it smoothly. Once they accept whatever metaphysical screwiness has allowed for them to communicate, they soon realize that Frank’s death is imminent. Of course, John’s life was profoundly (and negatively) affected by his father’s death, and so it is understandable that he would wish to prevent it. Arguably, the film would have been better if it had ended when Frank survives the fire with John’s guidance. It is a joyous, sweet, family-friendly story with an exciting climax.

Instead, when Frank gets back on the ham radio, we discover that John now has new memories.1 Their manipulation of the past led to the death of John’s mother—Frank’s wife Julia (Elizabeth Mitchell)—at the hands of a serial killer. And now, instead of his father dying in a fire thirty years ago, he has died of lung cancer. The rest of the film is a pseudo-timetraveling investigation into the Nightingale murders, with John uncovering new evidence in the present and Frank taking actions in the past to prevent them.

The practical elements of the “time travel” are never explicitly spelled out. At one point, Frank hides evidence in a loose floorboard so that John can find them thirty years later. In another scene, Frank, unable to get ahold of John on the radio, scribes “I’m still here, Chief.” into the desk with a soldering iron. John literally sees the letters being formed as they are etched into the surface, with smoke and everything. In the film’s climax, both father and son are fighting with the serial killer (portrayed by Shawn Doyle) in the same house but separated by thirty years. In 1969, the killer’s hand is mutilated by a blast from Frank’s shotgun, and we see it wither away in front of John’s face in 1999. It’s easy to get caught up in the moment and refrain from traveling down lines of thinking that might raise issues with the film’s continuity. But the film clearly isn’t concerned with that. Instead, it plays each moment with sincerity and heartfelt intent rather than mathematical consistency. It is one where you must “suspend your disbelief” to receive what the movie has to offer.

Quaid and Caviezel’s rapport is what makes the film worth watching. The pair had worked together on Wyatt Earp (1994) and Any Given Sunday (1999, though Caviezel’s scenes didn’t make the final cut), and elevate Frequency beyond its contrived plot because we believe that their relationship is genuine. Director Gregory Hoblit, who had two features (Primal Fear and Fallen) under his belt at this point, proves competent with the material he is given. He adds some artistic flourishes—some nice uses of montage, a few instances of slow motion, and a nice cut from a group photo while watching the World Series to crime scene photos when investigators discover the first Nightingale victim in the future—that leave a notable artistic fingerprint on the film without calling too much attention to itself.

Following the year after The Sixth Sense, I think Frequency was overlooked because of its similarities to that film. It’s not quite as tight as Shyamalan’s effort, but it’s certainly more emotionally resonant and maybe even more entertaining. And that’s what sets it apart from most films of the time travel genre. Usually, these films are doing one of three things: trying to be smart—Primer, Source Code, Edge of Tomorrow, Interstellar, Arrival—trying to be funny—Back to the Future, Hot Tub Time Machine—or trying to be romantic—Groundhog Day, The Time Traveler’s Wife. The best comparison I can think of for Frequency belongs to the latter group, a cute little romantic comedy called About Time, which wraps its romance in a time-traveling shell that is as much about the relationship between a father and son as it is about romantic love.

If you need everything to add up for a movie to land with you, you may want to skip this; but if you are willing to suspend your judgement and be swayed by good acting and a heartfelt story, you’ll enjoy it.

1. John is the only character who retains both his old and new memories, which is one of the most glaring creative liberties the writers took.