“To commit yourself is to run the risk of failure, the risk of sin, the risk of betrayal. But Jesus can deal with all of those. Forgiveness he never denies us. The man who makes a mistake can repent. But the man who hesitates, who does nothing, who buries his talent in the earth, with him He can do nothing.”

Where Malick’s The Tree of Life stretches to embrace the totality of all creation, from beginning to end, To the Wonder is a comparatively focused effort, honing in on the ephemerality of emotional love and the ramifications of letting our volatile passions rule our lives. At least that’s my read on it.

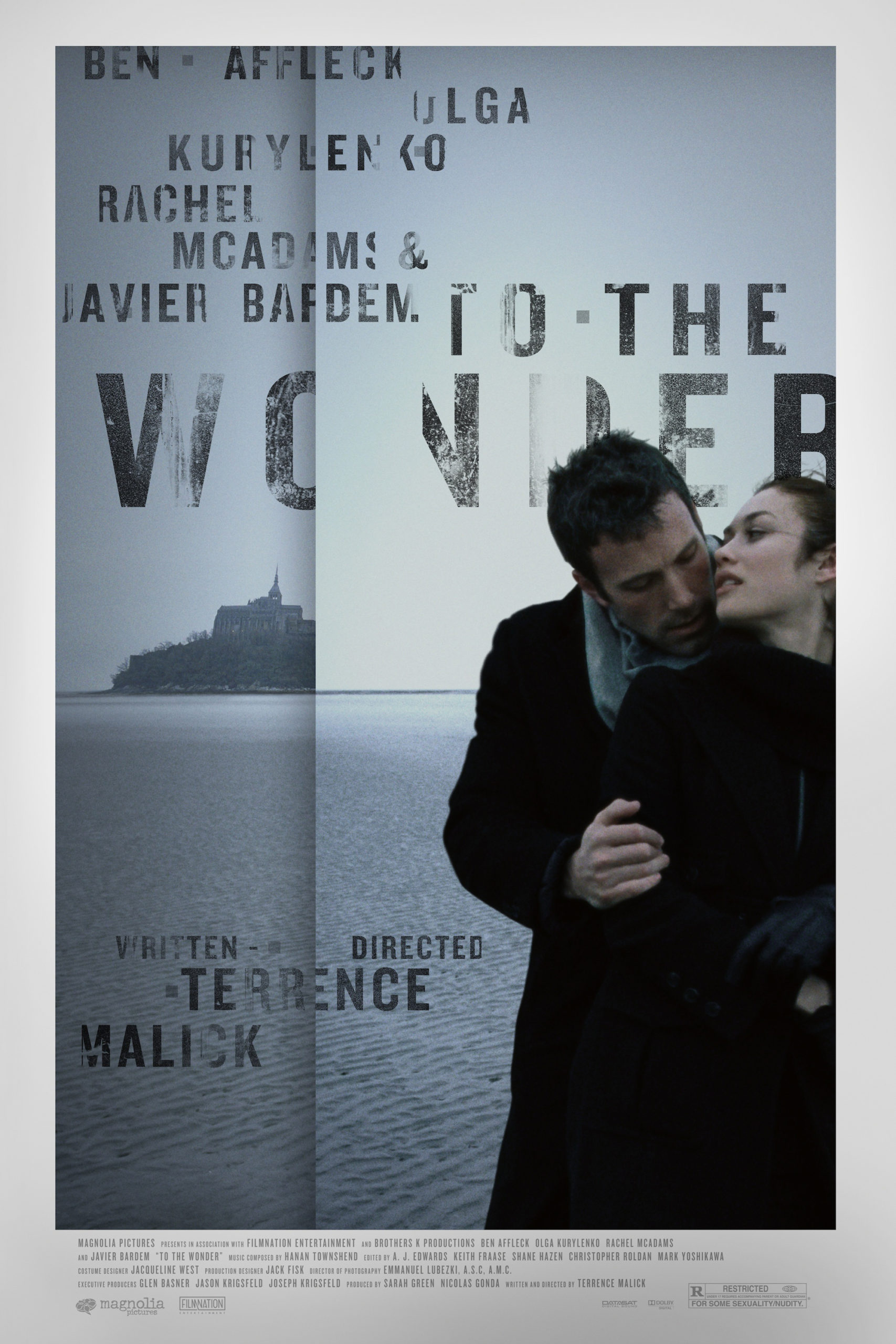

In his patented lyrical-mosaic style, which alone may produce oceanic feelings, Malick unfolds a narratively rich, sparsely plotted story about an American (Ben Affleck) traveling abroad who falls in love with a Ukranian divorcée (Olga Kurylenko) against the backdrop of ancient cathedrals, Parisian streets, and glimmering waterways. We experience their idyllic romance primarily through montage, classical music, and poetic (borderline platitudinous) narration, only occasionally settling into a particular moment for the shortest of illustrative vignettes before moving onto another stirring image—a swing carousel, stained glass church windows, footprints in wet sand.

But even as the drama moves stateside when the woman and her daughter (Tatiana Chiline) relocate to the man’s native Oklahoma—a decidedly less inspiring location—Malick and cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki continue to craft each image, no matter how mundane, as a paean to the overwhelming glory of God. In this way, laundromats, supermarket aisles, and Sonic drive-throughs take on a spiritual aspect, emphasized by the interspersed homilies from Father Quintana (Javier Bardem)—an anguished man of the cloth in the mold of Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest—which speak of the difference between divine love and human love and mankind’s innate posture of worship.

After a time, the romance cools. Mother and daughter, feeling an acute sense of dislocation, return to France. But there too they suffer from discontent. The man rekindles an old flame (Rachel McAdams), but again finds himself unwilling to commit to the relationship. The rest of the film features the tangential stories of these principal characters as they experience spiritual vexation and strain to manifest something to rival divine love from the finite reservoirs of other people. Even so, Malick refrains from an easy resolution, as the woman seeks solace in church traditions only to find a disillusioned priest unable to offer comfort, his wavering faith echoing their fading infatuation, foregrounding the metaphor of the Church as Christ’s bride. Later, Father Quintana finds spiritual renewal through showing Christ’s love to the impoverished and imprisoned, but the tension is never fully resolved.

In his excellent essay “Terrence Malick and the Christian Story”, David Roark considers Malick’s “liturgical” style of filmmaking—how he uses narrative form, aesthetics, kinesthetics, music, poetry, repetition, silence, and so on, to “not only stir thoughts and emotions but to shift and shape them.” Like liturgies, Malick’s films are crafted so that the message will “sink deep into our bones.” Throughout his career, Malick has used historical settings as backdrops for abstract narratives that instill the Christian ethos—the “way of grace” that is explored in The Tree of Life. In To the Wonder, his first film set entirely in the present day rather than a mythic version of the past, the moral is that we are creatures of habit, and that if we can begin to override our emotional whims with willfully righteous acts—serving those in need, committing to a spouse despite waning infatuation—the “way of grace” will start to replace our inborn “way of nature.”

These films do not just reflect a Christian worldview, but actually propagate the tenets of the faith and demonstrate how to meditate upon them. But, as anyone who’s spent considerable time in church can attest, worship services, be they liturgical or otherwise, are not always engrossing moment-by-moment. Rather, it is through repetition of core truths via hymnody, faithful exegesis of scripture, and the sacrament of the Eucharist that the Christian, over the course of a lifetime, is brought into righteous alignment. This is how the cinema of Terrence Malick functions, in miniature. How many critics cite a rewatch of a Malick film as a revelation, in the same way that a Christian will have an epiphany after reading the same bible verse for the umpeenth time? To the Wonder is certainly deliberate, repetitious, meditative, and enigmatic—Nick Olson makes the case that it should be seen as a kind of psalm—and could be dismissed on those grounds, but it is those very qualities that allow it to work its way beneath the skin and urge us toward the furtherance of the Kingdom of God; to suggest the spiritual riches that come from committing to the way of grace by grounding our identity in the eternal and unchanging love of our Creator—“a love that loves us,” as the film puts it, “from nowhere, from all around.”