“The shadow of death is upon your face. Have you seen a ghost?”

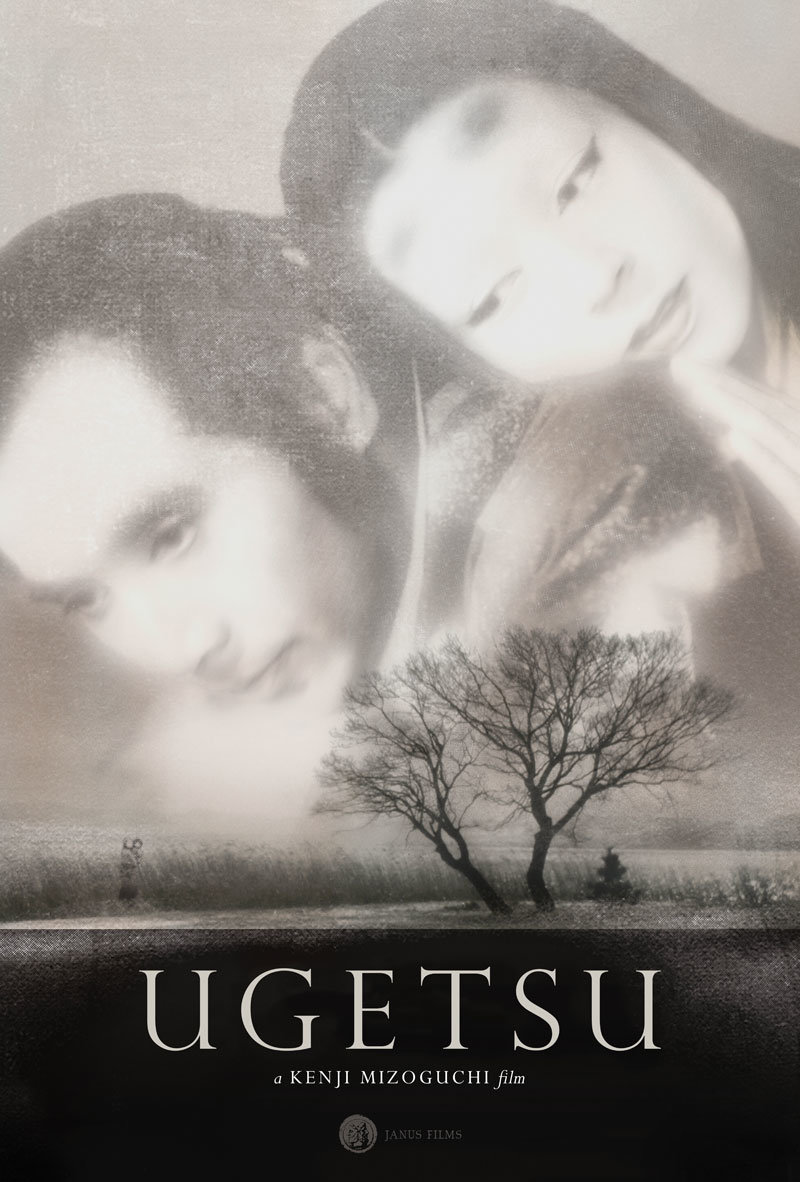

Kenji Mizoguchi was an incredibly prolific Japanese filmmaker who directed a string of masterful films late in his career. Among them are classics such as The Life of Oharu and Sansho the Bailiff. Sandwiched between those two is Ugetsu, a heartbreaking tale of ethical failure blended seamlessly with a ghost story. Ugetsu, along with Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon, is credited with popularizing Japanese cinema in the West.1 The film is based on Ueda Akinari’s 1776 short story collection, Ugetsu Monogatari, which translates roughly as “Tales of Moonlight and Rain” (or maybe it doesn’t; but that’s the English title it was given).

There are two stories, told in parallel, of two men from a small farming village whose ambitions lead them to sorrow. Set in the late 1500s, the film begins with the village preparing for attack. Despite this, Genjūrō (Masayuki Mori), a potter, continues packing his pottery pieces. Once the conflict moves on, his wares must be transported to a larger city with a marketplace where potential customers will see them. Tōbei (Eitaro Ozawa), an aspiring samurai, helps Genjūrō transport his pottery to the marketplace.

They return home safely, with a large sum of gold for their efforts. Genjūrō asks his wife Miyagi (Kinuyo Tanaka) to weigh the gold in her hand and presents her with a gift of fabric bought in the city. But he fails to comprehend when she says that the gift means less than his love for her. He merely continues on about gold and pottery, and sets about making more things to sell. While in the city, Tōbei had tried and failed to join a gang of samurai, who chased him away due to his lack of armor and a spear, calling him a “dirty beggar.”

When the conflict then arrives in their streets, Genjūrō bravely ensures the kiln stays burning even while soldiers move through the village to take men for forced labor. This time, instead of a wagon to transport the goods, the men believe it will be safer to take a boat across the lake. As the men travel across a lake with their families, another boat approaches them with a dying man aboard, who warns them to return home, saying that he was attacked by pirates. Despite protests, the ambitious Genjūrō drops Miyagi and their young son on the shore, and continues on with Tōbei and his wife Ohama (Mitsuko Mito). This scene is one of the most gut wrenching. It features beautiful shot composition—the calm lake, the fog, the single boat eerily floating appearing from within the mist—but shows Genjūrō completely abandoning his family in an unfamiliar place during wartime. All this for the chance to satisfy his greed.

The pottery sells well, and Tōbei quickly takes his share of the profits and runs off to buy armor and a spear. He joins the conflict, and sneakily kills a samurai who has just beheaded a great general, cheating his way to unheroic glory. He presents the head of the warrior to the commander of the victors, who rewards Tōbei with a horse and an entourage of soldiers. To celebrate, he takes his men to a brothel, where he finds the abandoned Ohama arguing with a patron who has tried to leave the brothel without paying for her services. Stunned that Ohama had become a geisha, Tōbei learns that Ohama had been raped by soldiers after Tōbei had left her. Tōbei’s scenes alternate between his comic antics and his gravely serious moral shortcomings. His ending is the happier of the two, as he promises to buy back his wife’s honor and throws his armor into the river as they return home together.

The more dominating and compelling story of the film is that of Genjūrō, who is approached by a mysterious and alluring lady one day in the marketplace. Lady Wakasa (Machiko Kyō) wears a large straw hat and a veil, and smudges of make-up sit high on her forehead.2 She requests that he deliver the pieces to her castle, Kutsuki Manor, where he is soon lured into a dangerous relationship with her. He is mesmerized by her beauty and is convinced to marry her, despite his current marriage to Miyagi. He repeatedly falls victim to her overpowering seductions and cannot force himself away.

One day, as he is returning from the city, Genjūrō encounters a Buddhist priest who recognizes death on his face. The priest paints symbols of exorcism all over Genjūrō’s skin, which seems to burn Lady Wakasa whenever she tries to embrace him. There is a neat filmmaking trick as Genjūrō swings a sword wildly as he makes his way out of the house: as he takes a random swing, he hacks through a lit candle, causing the room to darken. He collapses as soon as he is beyond the boundary of the Kutsuki Manor. He wakes up the next morning to discover that the mansion he had been living in with Lady Wakasa is charred ruins, abandoned some time ago.

Genjūrō returns home to find his wife and son at his old home. He is forgiven for his reckless ambition, and lays down to sleep with his son. The next morning, the village chief asks if Genjūrō is stuck in a dream, explaining that Miyagi has been dead for some time, stabbed by soldiers after Genjūrō dropped them off on the shore of the lake. Miyagi’s spirit speaks to Genjūrō, reassuring him. “I am always with you.”

Similar to fellow Japanese master Yasujiro Ozu, Mizoguchi liked to have long, planned takes of scenes that captured the entire moment in one shot.3 There is one in particular that stands out here. As Genjūrō bathes in an outdoor pool, Lady Wakasa joins him with water splashing up over the side. The camera follows the rippling water out into a grassy field where the two lovers are having a picnic. (I believe there is some trickery in the middle where two shots are stitched together—else how could the actors appear submerged in water, then fully clothed—but it is a stunning shot in any case.)

The film’s period setting feels legitimate. The marketplace, the public cautiousness, the brothels—all feel authentic, and give the ancient ghost story a solid platform upon which to unfold. It is obviously a fictional story, unlike the more plausibly realistic scenarios in some contemporary films, but it feels very true. That is to say, it conveys truth by telling a fictional story.

Ugetsu is the kind of film that you need to see to absorb. A retelling of the plot can’t convey its depth in storytelling, the skillful cinematography, and natural performances that make it so powerful. It’s allure is almost as subtle as the seductions of Lady Wakasa, the dark tale guised in Kazuo Miyagawa’s transcendent camerawork. The contrasts between the morally blind Genjūrō and the hardships suffered by Ohama and Miyagi are jarring; but both Genjūrō and Tōbei, having failed their ambitions and their wives, are able to find inner solace in the knowledge that they are loved and forgiven despite their failures.

1. Another of these breakthrough films was Teinosuke Kinugasa’s Gate of Hell (1953)—which also stars Machiko Kyō and was the first Japanese color film to be released internationally. It was the first Japanese film to win the prestigious Palme d’Or.

2. I do not know a lot about Japanese history and the different eras, but a few things used to be trendy that modern Americans would find strange. They blackened their teeth, painted their faces white; things like that. Removing the eyebrows and smudging them on higher up on the forehead is a practice known as hikimayu (yes, yes I did google “Japanese eyebrow smudge” to find the correct term). Machiko Kyō wears similar make-up in Rashomon (1950), as does Mieko Harada in Kurosawa’s Ran (1985).

3. Ozu is probably the name most associated with single takes, even going so far as to keep his camera completely still for long takes. Although he has many notable films, some of his that garnered more popularity in the West include Tokyo Story (1953) and Floating Weeds (1959), the latter of which also stars Machiko Kyō, who was just all over Japanese cinema in the 1950s.

And the way the story unfolds gradually building up the tension while at the same time treading on that fine line between dark and light, good and evil, is just amazing how that was done in terms of sentimentality.