“I’ll have you know the first two points scored in the NBA was a Jew.”

As the story goes, Uncut Gems was conceived in the minds of Josh and Benny Safdie long before they had the means or clout to get it off the ground. Learning the ropes by making microbudget short films, then a few independent features and a documentary, they finally had minor breakthroughs with Heaven Knows What and Good Time. The latter, a chaotic thriller with notable stars, proved the indie filmmaking brothers could handle a large production and allowed them to secure funding for their long-gestating story about a charismatic gambling addict who gets mixed up with a priceless opal and an NBA superstar. It’s the kind of story you love to hear, similar to how Christopher Nolan worked on the script of Inception for ten years while he helmed progressively larger films and honed his skills in preparation for his dream project.

Most interesting is how they carefully developed the story against a real-world backdrop. The screenplay always called for a real professional basketball player as a main cast member—Kobe Bryant, Amar’e Stoudamire, and Joel Embiid were all considered—and once they settled on Kevin Garnett, the script was reworked to integrate actual games that Garnett had played in during his outstanding career (it even makes a nifty connection between the player’s name and the phonetically identical gemstone). A few years into retirement by the time filming began, Garnett plays a younger, professionally-active version of himself. Having recently relished Julius Erving’s cameo in Jonathan Demme’s Philadelphia, seeing Garnett take on such a noteworthy role is a treat. Similarly, R&B singer the Weeknd features in a less prominent role, as the timeline aligned with his early career rise to stardom. A couple of other non-actor NYC celebs also have small roles.

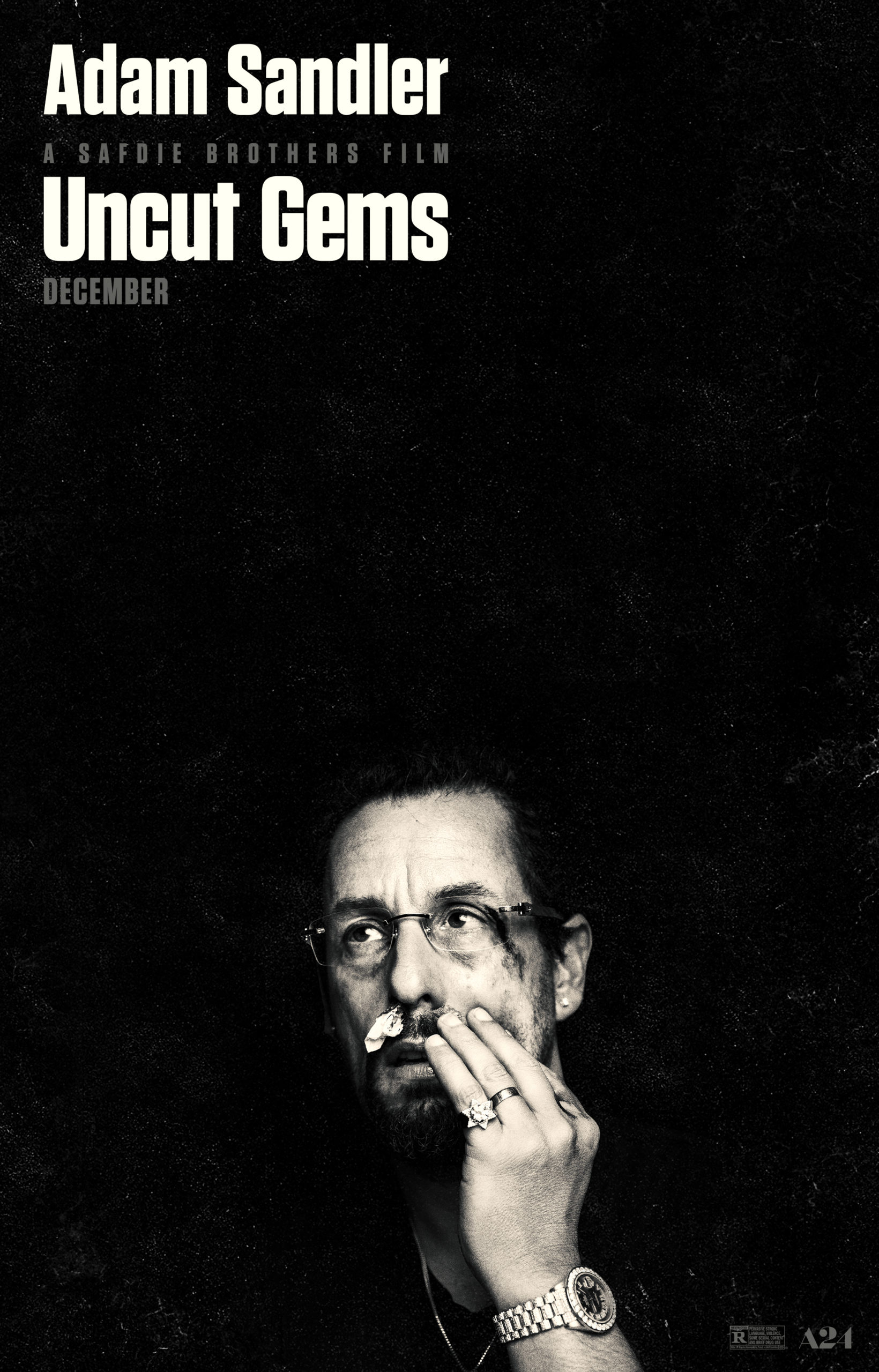

Set in 2012, when Garnett was part of the “Big 3” in Boston along with Paul Pierce and Ray Allen, Uncut Gems is, at its core, a ‘70s-styled character study centered around Howard Ratner (Adam Sandler), a disreputable, irksome, loud-mouthed jeweler from NYC who is deeply in debt with several loan sharks, primarily his brother-in-law Arno (Eric Bogosian). His personal life is similarly disastrous, as he splits his free time between his wife (Idina Menzel) and kids (Jonathan Aranbayev, Noa Fisher, Jacob Igielski), and his girlfriend Julia (Julia Fox), whom he also employs. But for a guy like Howard, homelife has little meaning—his thoughts are always dominated by the next big score.

Two noteworthy developments occur right on top of one another within the confines of Howard’s upscale jewelry store. First, his associate Demany (Lakeith Stanfield) brings Kevin Garnett in as a potential customer. Second, he receives a covert shipment containing a rare cluster of black opals smuggled out of Ethiopia by Jewish miners (detailed in an extraneous prologue). Excited that a celebrity is currently perusing his shop, Howard gleefully shows off his new treasure to the Celtics’ superstar. Garnett becomes so entranced by the gem—in one of my favorite sequences in the film, we see into the player’s mind’s eye as he glimpses a montage of past and future events while gazing into the stone, an illusion broken when his weight on the glass countertop causes the pane to shatter—that he demands Howard let him buy it. Problem is, Howard’s already lined it up for auction. The best he can do is loan it in exchange for Garnett’s 2008 championship ring. They make plans to reverse the exchange in a few days, but, because Howard is an idiot, he senses a new opportunity. He quickly pawns Garnett’s ring and uses the money to place a six-way parlay on Garnett’s game, correctly predicting that the gem contains some mystical mojo that will positively influence the player’s performance.

As the plot unfolds, Howard digs his hole deeper and deeper by taking crazy risks and lying through his teeth, trying to reacquire the opal and sell it to pay off his debts, until a climax finds him holding Arno and his two thugs (Keith William Richards, Tommy Kominik) hostage while he watches a Celtics game with over a million on the line.

Utilizing a similarly frenetic structure and tone to Good Time, Uncut Gems rarely goes for more than a minute or two without a moment of teeth-grinding intensity, whether that comes from contentious conversations in the jewel store, shouted arguments beneath the blacklight of a concert, or violent assaults intended to knock some sense into our weaselly anti-hero. This grueling texture is ably supported by an ‘80s-inspired soundtrack courtesy of Daniel Lopatin (of Oneohtrix Point Never fame), which is both ethereal and discordant, and a masterful sound mix that emphasizes overlapping, shouted dialogue, door buzzers, car alarms, and the constant din of downtown NYC. The camerawork—less attention-grabbing than the sound design—also works toward the aim of constant anxiety. It’s very energetic, borderline physically exhausting in its relentlessness, as it sprints through these few weeks in the life of a true adrenaline junkie.

What falls out of this is orchestrated pandemonium. Many critics have elected to smother Uncut Gems in weirdly backhanded compliments along the lines of “all of this shouting and swearing and fighting would be incoherent in lesser hands.” Or, put another way, perturbing the viewer with a chopped-up cacophony of sensory input is the end goal; the Safdies have achieved their objective if you finish the film with a pounding headache and a desire to metaphorically put a few more bullets into Howard Ratner’s noggin. But this commitment to intensity, while admirable in its own way, doesn’t seem like a worthy aim in and of itself. Such a demanding sensory assault doesn’t lend itself to a pleasurable viewing experience, and so we must question if the style was employed for any other reason than grinding the audience into dust. The only plausible answer is that this mirrors the overwhelmed psyche of the protagonist, which makes some sense. The stylistic commitment is only undercut in the final moments by an ending that feels slightly like a cop-out, as if the preceding tone would have clashed with the logical outcome and so a shocking twist had to be grafted on. (In isolation, though, the synth-soaked violence of the climax is a winning combination.)

Ultimately, Uncut Gems is the kind of film that feels like it needs a second viewing, as loath as I’ll be to rewatch a movie that intentionally annoyed me from its opening frame to its last. The first time, you feel that overbearing sense of deliberate aggravation as rabid fiends bark at one another, Lopatin’s synths pulse, and the handheld camera ducks and dives amidst the grimy neon of NYC. By the end of the endurance test, you’ll feel like you have a personal vendetta against Howard Ratner, maybe even the Safdies themselves. The second time, dispassionate and analytical now, you’ll note just how those various ingredients have been meticulously layered to produce the effect felt the first time. But is critically analyzing how something can be both well-made and annoying worth my time? I’m not so sure.