“Everyone creating is a member of the family,

Passing down genes and ideas in harmony.

The players and the cynics might be thinking it’s odd,

But if you rewind the tape, we’re all copying God.”

Oja Kodar and Vassili Silovic’s 1995 documentary Orson Welles: The One-Man Band depicts the maverick filmmaker as a consummate tinkerer, a man who took his editing table with him wherever he went, who conjured life-giving poetry and magic from the juxtaposition of sound and image. F for Fake, his last feature completed in his lifetime, is his most experimental work. It delves into themes of authenticity and authorship with such uncommon energy and personality that when it transcends its subject matter with its own stylish smoke-and-mirrors act, one can’t help but revel in its deceptions. Throughout, Welles exposes the rough edges of the filmmaking process. He points at all of those loose-stitched seams that mainstream filmmakers dutifully conceal and gleefully says, “Look at this! Look how easily you are manipulated!”

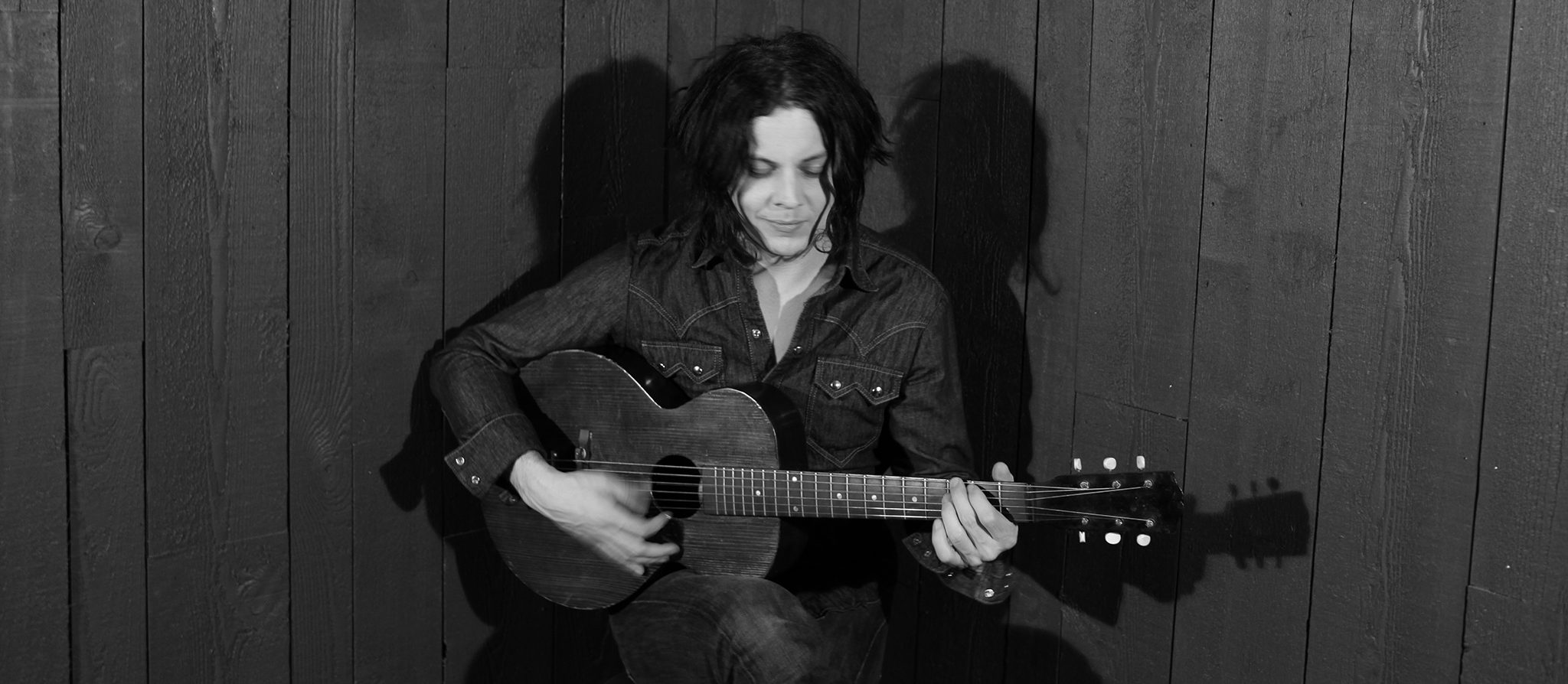

Jack White, a self-avowed Welles fanatic—he named his record label after The Third Man and repurposed a monologue from Citizen Kane on ‘The Union Forever’—attempts to follow in his idol’s last footsteps on Boarding House Reach.

In the halcyon days, circa Elephant give or take a few years, White was a consummate songwriter, drawing on the rich traditions of blues, garage, and folk music to keep the spirit of rock ‘n’ roll alive. He was also something of a Luddite, allowing himself the limited use of certain technologies, but always favoring the authenticity of single-take analog recording. He embraced the organic imperfections that arose from the process and regarded digital manipulation as a form of artistic fraud.

All that’s changed on Boarding House Reach. For the first time, White’s reversed course and decided to try out a few modern tools of the trade, namely ProTools—an indulgence that has had a profound and polarizing effect on his approach to songwriting. Effectively, these newfound editing and song-construction techniques have unlocked a weird, jittery other side of the man’s brain that’s positively bursting with ideas.

Unfortunately, these ideas are apparently so overwhelming that White can’t be bothered to wrangle them into coherent songs. In fact, he’s arguably not writing songs at all so much as he is stitching together a patchwork of every half-formed whim that wanders into view.

Unlike his first two solo albums, Blunderbuss and Lazaretto—solid modern rock albums, to be sure, but rather safe and predictable—Boarding House Reach is chaotic and impulsive. It assaults the listener with disparate sounds held up in shaky juxtaposition. P-funk grooves give way to conga breakdowns, country twang is interspersed with 808 drum loops, spoken word diatribes are set against gospel choirs and organs, Carpenter-esque synths vs. tremelo riffs. He even tries a Beck-inspired rap on ‘Ice Station Zebra’ and is not entirely unsuccessful, and his trademark yelp is sampled with abandon. It’s a madcap hodgepodge. Which is not to suggest that White never experimented in the past—he did—but to underscore the fact that he’s no longer trying to fit his craft into the confines of conventional songwriting.

However exciting the album may sound in concept, it never fulfills its potential as a scatterbrained meta-rock odyssey. Like F for Fake, the album moves forward with a propulsive energy and magnetism that serves to disguise its threadbare quality even while calling attention to the process of music production. You can identify all of its seams and grafts. But unlike the film, it doesn’t have that additional magical layer wherein despite the self-exposure of its artifice, it dazzles you anyway. When you ruminate on Boarding House Reach for any length of time, you come up with nothing. Contrasting its earnest if banal lyrics, the cut-and-paste texture of the tracks saps any emotional punch. The thrill of hearing incompatible sounds mashed together into something vaguely functional is dampened by the overall lack of coherence and flow (to wit, the euphoric story of Jack White discovering how to play a piano chord is a neat anecdote, but I don’t need to hear it immediately following the spoken word ‘Ezmerelda Steals the Show’). And no matter how tasty one finds the gaudy riff on ‘Corporation’, it never rises above the level of a fun jam. It’s hard to believe the almost lyricless six minutes are a worthy successor of, say, ‘Ball and Biscuit’. If F for Fake pleasurably deceives even as it elucidates its methods, Boarding House Reach merely does the latter.

And so what falls out is not a dazzling showcase of its creator’s eccentricities, but rather a loose assembly of promising false starts—some of which threaten to rise to the occasion but none of which have staying power. White has seemingly abandoned his desire to capture the zeitgeist with another ‘Seven Nation Army’ or to carry the rock ‘n’ roll torch, which is certainly his prerogative, but this provocative new direction has thus far proven more exciting in conception than execution. It’s too off the wall to ignore, yet too unmoored and unfulfilling to warrant many spins.

Favorite Tracks: Corporation; Ice Station Zebra; Get in the Mind Shaft.

Sources:

Hurst, Josh. “B for Bullshit: Truth, nonsense, and Jack White. John Hurst on Records. 5 April 2018.

Martin, Adrian. “F for Fake”. Film Critic: Adrian Martin. June 1996.