“Believe me when I say rock ‘n’ roll is here to stay.”

It’s pretty much impossible to talk about Esquerita without talking about Little Richard, so let’s get on with it. Known in certain circles as the Architect or even the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll, Richard Wayne Penniman achieved great fame and recognition for his flamboyant showmanship, which combined the thrills of pop music with a rabble-rousing attitude and a charismatic spirit that was fostered by his upbringing in Pentecostal churches. He was a liberated soul in a straight-laced era. His early singles, massive hits like ‘Tutti Frutti’ and ‘Long Tall Sally’, were so transcendentally infectious that he became one of the first successful crossover artists alongside acts like Chuck Berry and Fats Domino, and as time has passed his influence has only become more widespread—some would suggest he had a hand in shaping not only rock ‘n’ roll, but also soul, funk, hip hop, R&B. When he first toured Europe, the Beatles asked if they could open for him! And just the other day my very own toddler caught the bug and started shaking her hips to ‘Good Golly, Miss Molly’ and ‘Lucille’. He didn’t burn bright enough long enough to be on Mount Rushmore, and his impact is hard to fathom without some very intentional contextualizing, but his place in the pantheon is no doubt secure.

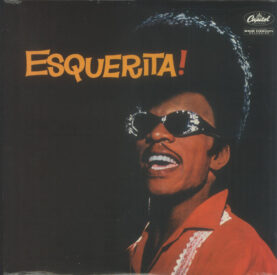

And but so what about Esquerita, that other ostentatious piano rocker raised on gospel music whose only non-posthumous release is a pithy self-titled blip on the radar of rock history that doesn’t even last thirty minutes and came out after Little Richard had already made his mark, repented of his extravagant lifestyle, and transformed into a traveling preacher? On a quick scan he’s a knockoff Little Richard, but to hear Little Richard tell the story, he more or less lifted his whole schtick from the guy. Richard’s the knockoff! Coming from such a raging narcissist it must at least contain the gist of the truth.

Unverifiable anecdotes are the lifeblood of rock mythology—ahem, mudshark—and the legend of Esquerita supports this notion. Take a listen to early Little Richard—not the debut album but the singles that came before that; pleasant enough but nothing like the caterwauling devil music he’s famous for. Indeed, repenting from his wild ways and re-emerging as a minister was not Richard’s first transformation. That happened when he met Eskew Reeder Jr., a rhinestone-and-pompadour maniac who had been pounding the piano and channeling the spirits of pagan gods for several years. Just not on record. No, see, if we are to believe that early takes of ‘Tutti Frutti’ were X-rated and Little Richard was forced to clean it up for the studio recording and mass release, we must believe that Esquerita is the one responsible for that vulgarity and the elements of luridness, swagger, and flamboyance that came to define Richard’s image.

Judging from the scant, scattered bits of biography one can dredge up, it seems that one of the reasons Little Richard is a household name and Esquerita is merely a footnote in his story is that the latter might have been content to luxuriate in the dynamic energy and freedom of live performance. He could play the dirty version whenever he wanted. Or maybe he just wasn’t discovered by the right person until it was too late.

In any case, what we can nail down for certain is that nothing exists on record until 1958, when Paul Peek, a member of Gene Vincent’s Blue Caps, caught a show in Esquerita’s native Greenville and convinced him to record some demos. Then he talked Capitol Records into signing him to fill the gap left by Richard’s transition to a life of ministry just as the Blue Caps had capitalized on the sound of Elvis Presley.

Okay, so now take a listen to the early Esquerita singles (some of them collected on Vintage Voola), forgetting for a minute that they’re being laid down a few years after Little Richard’s rise to stardom. The whoops and shrieks, the wild slapping of the piano, the on-the-verge-of-collapse tempos—these are obviously traits that Little Richard borrowed. But there are differences too. Esquerita’s got a gruffer singing voice and a marginally sloppier playing style, for starters, but those can easily be construed as positives, no? For those who like their blues a bit rough around the edges, soaked with gin and held together with gutstring—for those who want to enjoy music but not necessarily view musicians as saints or even role models—Esquerita is one of those dudes. And where Little Richard cited the Most High as his guiding light (whether or not he was genuine or opportunistic is not for me to decide), Esquerita was unashamed to assign his mojo to a posse of demonic spirits he christened the Voola.

But—and there must be a but or else you’d know who Esquerita was—as George Starostin astutely points out in his own review of Esquerita!, the man’s talents did not extend beyond the realm of performance and into the realm of songwriting. While it seems correct to say that Little Richard based his musical style and campy stage persona on those of Esquerita, it seems equally correct to say that, at least by the time he was slightly tamed and corralled into a recording studio, Esquerita’s compositions were patently derivative of Little Richard. And not just of Little Richard, but of Muddy Waters, B.B. King, Jerry Lee Lewis, and several others, and none of them are quite as good, let alone better, than the songs they’re mimicking.

Which kind of makes sense, because, as I mentioned earlier, one plausible explanation for not recording until the late 1950s is that Esquerita didn’t really care about parlaying his music into fortune and fame; he just wanted to get caught up in the ebb and flow of a rock ‘n’ roll performance—how is that for mythology? And so anyway we have this second-rate rock ‘n’ roll album, granted one performed with an abundance of flamboyance, but one made without much emphasis on creativity or discipline or polish, that hit record store shelves a few years after that initial boom but before it was far enough in the rearview to warrant a revival. No wonder it was cooly received and faded into obscurity. Still, it’s a fun record despite all that, and it’s always enjoyable to discover those true mavericks who did their own thing and remained true to it even if that thing led to the underground instead of popular success.

Esquerita would toil away for another twenty some years as an inversion of Little Richard, plying his trade and never quite finding a niche, never making any money, never kicking drugs, never finding redemption, and sadly dying of AIDS in 1986. He’s buried in an unmarked grave.

Favorite Tracks: Hey Miss Lucy; Get Back Baby; Hole In My Heart.

Sources:

Woods, Baynard. “Esquerita and the Voola”. Oxford American. 19 November 2019.