“I’m lying down,

Blowing smoke from my cigarette,

Little whisper smoke signs that you’ll never get.

You’re in your Oldsmobile driving by the moon,

Headlights burning bright ahead of you.

And someone’s burning out, out on Condor Avenue.

Trying to make a whisper out of you.”

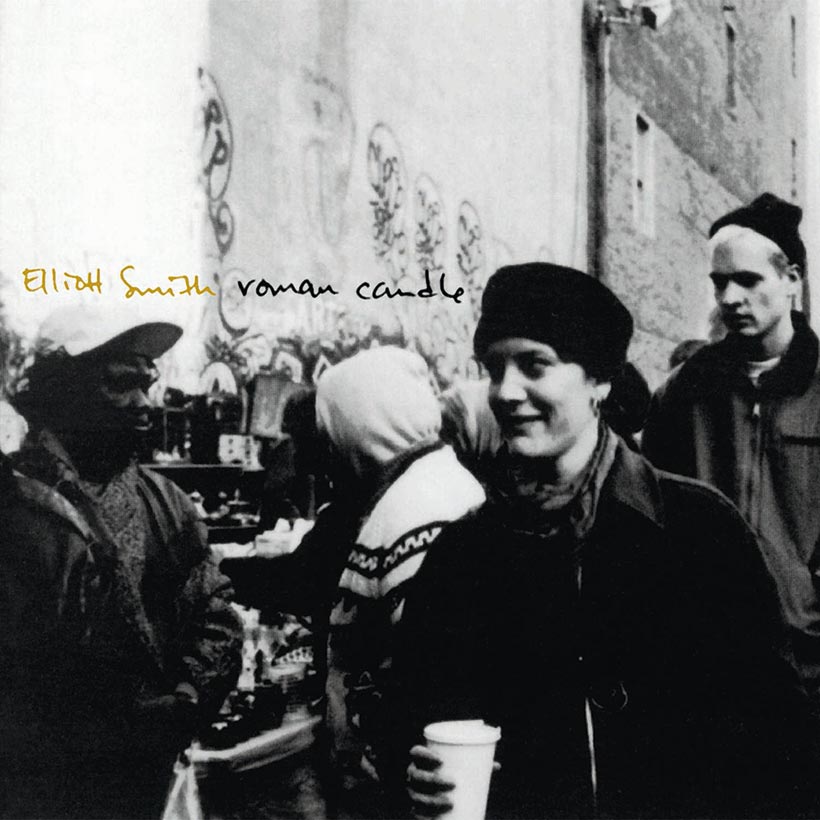

Roman Candle is a sparse, spindly, and short debut solo album from Elliott Smith. At barely thirty minutes in length, it goes down easy as the minimalist songs transition smoothly between one another, though each remains distinct. There is little polish; it sounds like Smith preferred to create a song and get it down, then move on to create something new rather than tinker endlessly trying to find additional magic. The squeaks of guitar strings during chord changes and vocal imperfections abound—the mix tastefully shows the seams of the art. Smith’s vocal delivery is a raw and his lyrics tend to be used for conveying mood and creating hazy mental images rather than any sort of storytelling.

Coming after only the first of three albums with his college band Heatmiser, the album was recorded in the basement of J.J. Gonson, manager of Heatmiser as well as Smith’s girlfriend at the time. Recorded as a demo, Gonson presented the songs of Roman Candle to Portland label Cavity Search Records (who had released several singles by Heatmiser) to try and secure a 7” single release for Smith as a solo artist. Upon hearing the demo reel, the label requested to release the entire thing; although Smith was initially uncertain, he allowed the album to be released.

Smith used a four-track recorder to capture his playing, manning each instrument himself, which results in a homespun, undisguised sound. The songs present a stark contrast to the buzzy grunge-tinged rock of Heatmiser, showing the softer sensibilities that would distinguish Smith’s career after the dissolution of the band. Although his light melodies and acoustic picking bring to mind the sounds of Simon and Garfunkel’s Parsley, Sage, Rosemary And Thyme, Smith’s lyrics are colored by his harrowing bouts with depression and drug addiction. In the penultimate song, the lyrics paint an image of a loner upset with his immutable tendencies.

Last call

He was sick of it all

Asleep at home

Told you off and goodbye

Well you know one day it’ll come to haunt you

That you didn’t tell him quite the truth

You’re a crisis

You’re an icicle

You’re a tongueless talker

You don’t care what you say

You’re a jaywalker and you just, just walk away

Prone to depression, Smith’s most apt comparison is Nick Drake, a similarly haunted singer-songwriter whose output was cut short due to an early death three decades before Smith would meet a similarly abrupt end. The comparison between the two is valid not only based on the lyrical content, but in the subdued vocal delivery and the subtly crafty fingerpicking as well. One nebulous trait that sets many of Smith’s sparse songs apart is their fullness. Compare ‘Condor Ave.’ with ‘Independence Day’ from his 1997 album, XO—both songs are driven by an acoustic guitar, and both sound complete, yet the latter is fuller with its drums and second vocal track, while the former is populated by only Smith’s intricately plucked acoustic and his voice mingled with tape hiss.

A trick that many of the songs play on the listener is in their mismatched pop sensibilities and dark lyrical matter. In the title track, Smith rages against his abusive stepfather, not with the specific details of a storyteller, but in the hazy images of a poet. “I want to hurt him, I want to give him pain. I’m a roman candle, my head is full of flames.” Although confessional music like this can often be dismissed as overly soft-hearted or indulgent, Smith’s lyrical talents bring to mind the master of the form. Recalling Bob Dylan’s vulnerable 1975 album Blood on the Tracks, Smith’s tracks oscillate between murky fictional third person narratives and first person accusatory torrents, and though most songwriters inevitably write from a personal perspective, Smith’s lyrics tend to more obviously be self-portraits.

Regarding his influences, Smith stated: “Probably the Beatles, and then Dylan. […] I love Dylan’s words, but even more than that, I love the fact that he loves words. […] I like folk songs but it is a very defined genre and I think it’s not really what I play. For me, the difference between folk and pop is that in folk there is a clear message in every song and there is usually a moral to the story. That’s fine but it’s not how I write. I like more impressionistic things, word pastings. Pop is broader, more things can be in it together.” The melding of the pop music of the Fab Four with the wordsmithing of Dylan is not something that Smith quite achieved this early in his career, but it is an incredibly lofty goal (Rolling Stone Magazine considers those artists as the first two entries in their 100 Greatest Artists list). Smith would go on to cover both artists in concert, and his subsequent efforts are much more indicative of their combined influence on his style.

In Smith’s indistinct collection of poetic self-analyses, his disparate characters are all similarly dispositioned toward self-destruction, seemingly stuck in emotional ruts through repetitions of harmful refrains. There are brief moments of respite (see ‘No Name #4’ in which the protagonist briefly escapes an abusive relationship), but throughout, his characters see a dearth of potential catharses and the inevitability of eventually returning to the desperate state in which they began. As I said earlier, Smith’s musical sensibilities help to draw the listener in to what would otherwise be an incredibly harsh listen. ‘No Name #2’ features a joyful harmonica on its chorus, and in ‘Last Call,’ when Smith indulges in some heavy electric guitar tones during the repeated refrain (“I wanted her to tell me that she would never wake me”), the stunning climax shows a soul locked in a gut-wrenching battle with his demons. The instrumental ‘Kiwi Maddog 20/20’ is almost needed as a light outro in order to come down from the emotional heights of the preceding tracks. The opener and closer here do not match those on the impeccably structured albums Smith would later release, such as XO (‘Sweet Adeline’ and the vocals-only ‘I Didn’t Understand’) and his sophomore effort, the self-titled Elliott Smith (‘Needle In The Hay’ and ‘The Biggest Lie’), but they’re pretty dang good.

A thoroughly haunting album, Roman Candle announced to the world—or at least the indie music world—that Elliott Smith was a musical force worthy of attention. His vulnerability and compassion buoy his instrumentally bare foray into a solo career. Recorded without an intention of wide release, the songs reveal an honest and cathartic songwriting process, one which Smith wouldn’t exactly move on from in his future endeavors. Although the content is retrospectively viewed in light of his tragic death by stab-wound, the material stands on its own merits, lo-fi recording, chord flubs and all.

Favorite Tracks: Condor Ave; No Name #1; Drive All Over Town.

Sources:

Nugent, Benjamin. Elliott Smith and the Big Nothing. Da Capo Press. 2004.

Shutt, S.R. “Elliott Smith: A Biography”. Sweet Adeline.

Costello, Elvis. Robertson, Robbie. “100 Greatest Artists”. Rolling Stone. 2011.

https://www.rollingstone.com/