“Like the scientists who made the hydrogen bomb, the men who really understand are troubled.”

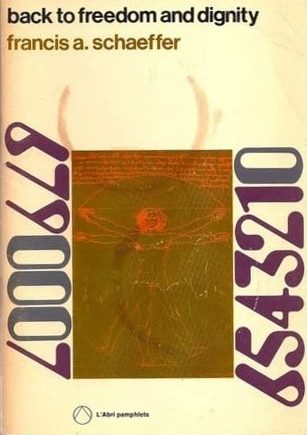

More of a long essay than a book, Francis Schaeffer’s Back to Freedom and Dignity is a response to B.F. Skinner’s Beyond Freedom and Dignity, among other essays and articles on similar topics. In a nutshell, Skinner’s work argues that man’s behavior is entirely determined by environmental conditioning, that free will and moral autonomy do not exist, and that mankind’s belief in such notions hinders the ability of authorities to use the scientific method to usher in a utopian future. The problem is that man has no intrinsic worth from that viewpoint and so those who hold it have no objections to all sorts of atrocities. Off-the-cuff, Schaeffer gives various counterarguments from the basis of the Christian worldview espoused in his first three books, tackling topics such as the removal of moral boundaries in scientific pursuit, the secularist’s religious reverence for science, and the anthropomorphization of “chance.” In only a few dozen pages he pokes a number of large holes in this newfangled belief system and makes a strong case against the horrid dystopia that its adherents envision for humanity.

Schaeffer’s primary goal in writing Back to Dignity and Freedom is to combat what he calls the “biological bomb”—the rapid spread in popular news sources of scientific findings regarding genetic manipulation. We are now within startling proximity of what could previously be found only in the realm of science fiction, even more so in the 21st century than when the essay was first written in 1972. Schaeffer was alarmed by the reductionist arguments of scientists like Jacques Monod (author of Chance and Necessity), who believed that “man’s existence is due to the chance collision between minuscule particles of nucleic acid and proteins in the vast ‘prebiotic soup.’” He also critiques the work of Francis Crick, one of the scientists who deciphered the structure of the DNA molecule. Like Monod, Crick believes that man is not a complex personal being made in the image of God but an electro-chemical machine. What’s curious is that these men approach their studies with a decidedly religious stance, often ascribing personal qualities to impersonal ideas. For instance, Crick describes natural selection as “clever.” But as Schaeffer lays out in He Is There and He Is Not Silent, if one begins with an impersonal force, adding time and chance to it cannot result in personality or intrinsic meaning.

And so without the moral guard rails provided by the Judeo-Christian worldview, scientists like Monod and Crick argue their case: since man is merely a sack of chemical responses to external stimuli, can’t we just mess around with his DNA? Can’t we just alter what it means to be human? To make the world a better place? But their definition of good—and thus their definition of better—has no philosophical backdrop. They’re stealing a term that doesn’t belong to their worldview and persuading by familiar connotation (which Schaeffer has written about previously and echoes here). “Good” for the secularist can be made up as he goes along. Within the brief excerpts provided in the essay we see the proposal of test tube babies, abortion, euthanasia, population control. We see aspirations to take over public education, to bar certain ways of thinking from universities, to alter behavior with brain surgery and drugs. A few raise wary objections. Speaking on embryo transplants, Dr. James D. Watson—who was awarded a Nobel Prize along with Crick for their work on DNA—said in an interview with Look magazine: “All hell will break loose. The nature of the bond between parents and children and everyone’s values about their individual uniqueness could be changed beyond recognition.”

The Bible has something to say about pretty much every issue that one encounters in life and this idea of moral boundaries is no different. You don’t even have to read very far. In the third chapter of Genesis, Eve commits the first sin of mankind. She does not violate the physical laws of the universe—her ability to eat the fruit is never in question—but she violates God’s commandment. She does something she should not do even though she is capabale of doing it. But the modern secularist finds himself troubled without that second boundary condition—there is no concept of “should” in this worldview—and thus, given his beliefs, he cannot find a sufficient reason to stop himself.

What’s especially alarming are the obvious questions that go unanswered once this whole sickening thought experiment is laid out. After Skinner has reduced man to a bundle of chemicals formed by external conditioning; once he’s excised his soul and his mind; once he’s dismissed his personality and autonomy; once he’s shown that the Sistine Chapel was not a creative endeavor undertaken to glorify God but a chance result of chemical reactions; once he’s “eradicated not only morals but every vestige of everything that makes human life valuable from the standpoint of what God meant us to be as men in His image”—he still does not provide a coherent alternative worldview. The most obvious question, if we are to understand that man’s behavior is dictated entirely by his environment, is who gets to decide what ideal behavior is? Who gets to control that environment? Who gets to dictate human behavior? As Skinner’s belief system provides no method for defining “good” he must, through a brief discussion on positive reinforcement mechanisms, resort to the idea that survival—the biological continuity of the human race—is the sole value in the universe.

Here is another voice calling for the development of an elite that will set up arbitrary values, arbitrary absolutes whereby to control the world. Even if the goals are at first sight laudable—the salvation of the human race—the implications concerning human freedom are there for all of us to see. The problem is that with man being considered a product of the impersonal plus time plus chance, all values are arbitrary and open to manipulation.

Schaeffer identifies three additional questions that Skinner must answer if he wants anyone to take his ideas seriously (or if he wants anyone who studies his ideas to take them seriously, as many people nowadays like to take things very seriously without taking much time to understand them). First, will there be a new second boundary condition to replace the moral system of the Bible, or is everything permissible? This seems untenable in Skinner’s totalitarian utopia. Next, why does the survival of the human race have any value at all? After all, we are no different than dogs, or bacteria, or rocks. Positive reinforcement does not signify intrinsic value. Lastly, if man is so poor at self-observation that he consistently concluded for tens of thousands of years that man is different from non-man, then how can we trust his observations on anything? And don’tcha know, Skinner is a man.

On Skinner’s view, we must take a skeptical approach to our entire existence and everything we know. But let’s back up a second and make sure we comprehend just how asinine Skinner’s position is. If Skinner acted on his professed beliefs, he would be logically functioning within a system he believes does not exist. He believes that man is nothing but a blob of chemical reactions and that individual personalities do not exist. And yet, in the same breath, he requests that we hand him over our brains so that he can play god and “improve” our behavior. The man who does not believe in free will or the concept of good wants to dictate how people act via surgery, medication, and genetic manipulation. The gall! I suppose, on Skinner’s view, he cannot call foul play if he’s stuck in a loony bin? (Yeah, he’s been dead for like thirty years, but my point stands.) After all, if man qua man doesn’t exist we can’t be faulted for simply reacting to our environment.