“The very basic core of a man’s living spirit is his passion for adventure. The joy of life comes from our encounters with new experiences, and hence there is no greater joy than to have an endlessly changing horizon, for each day to have a new and different sun.”

—Christopher McCandless AKA Alexander Supertramp

In late 1992, Jon Krakauer wrote an article for Outside Magazine titled “Death of An Innocent” that described the demise of Christopher McCandless. The story got a lot of attention, and Krakauer could not shake the story from his mind, and so he continued researching and expanding on his piece until he had what he considered to be a more or less complete account of the enigmatic wayfarer and his fated pilgrimage; the result, Into the Wild, was released in 1996. Though the book remains controversial—some idealistic or disillusioned young people nearly sanctify McCandless,1 while experienced outdoorsmen and local Alaskan’s scoff at his incompetence and foolhardiness—it is an engaging read, and stirs the latent primal urges that are gradually quelled as we mature and become more cautious.

The polarizing nature of the book is due to the complex character of McCandless. Having watched Sean Penn’s film adaption of Into the Wild, and conversed with several people regarding the story, it seems that you are either awed by his philosophical, literate, and mystical approach to life, or you are repulsed by his selfishness and hubris, and disgusted at the way his careless decisions hurt those who loved him.

In 1990, after graduating from Emory University—where he studied history and anthropology—McCandless chose to forego law school and give away more than $20k to OXFAM (a charity focused on the alleviation of global poverty). He then began his life as a vagabond, meandering around the United States, working as a burger flipper or farm hand when funds were short. He didn’t immediately go to Alaska, but first went on several lengthy hiking trips, abandoned his Datsun in the Arizona desert, and canoed in the Colorado River. He was 24 years old when he hitchhiked to the forty-ninth state, trekked into the wilderness and never returned.

Into the Wild is effective because of Krakuer’s empathetic view of McCandless. As a young adventurer himself, Krakauer had spent a good deal of time in Alaska. He was more intrigued by its mountain peaks than in the prospect of primitive survival, but his personal defense of youthful compulsive risk-taking addresses the reader’s natural reaction to simply call McCandless suicidal. When Krakauer is through his story of climbing the Devil’s Thumb (which could have been self-serving but is mostly used to prop up McCandless), he doesn’t really see much of a difference in temperament between himself and McCandless. The only real difference is that Krakauer survived his reckless streak.

McCandless is probably only known because he died young, but that is not the reason his life is worth reading about. His determination to walk his own path as admirable. Krakauer includes comments from the McCandless family, as well as a number of people that crossed paths with Chris as he was travelling. These conversations with those who briefly knew him—not his grueling last days (which were recreated by Krakauer based on the terse diary entries left by McCandless)—are the strongest parts of the book. The people with whom he had hitchhiked, worked, bunked, and shared his life had quite positive things to say about him. The most touching of these encounters is with an eighty-one year old man whom takes Chris’s advice—he moves his belongings into a storage locker, buys a Duravan, and camps out at Chris’s old campsite, waiting for the boy to return. The anecdote simultaneously elucidates how magnetic Chris’s personality was and how much pain he inflicted on others by bowing out of their lives. The old man claims he left his church when he learned of Chris’s death; and when his parents visit the site where he died, his mother leaves a Bible there, but admits that she had not prayed since she learned of his death.

“I prayed. I asked God to keep his finger on the shoulder of that one; I told him that boy was special. But he let Alex die. So on December 26, when I learned what happened, I renounced the Lord. I withdrew my church membership and became an atheist. I decided I couldn’t believe in a God who would let something that terrible happen to a boy like Alex.”

While McCandless may have been a tad quixotic, he certainly wasn’t an imposter. He fought with his demons and followed his dreams. He lived the life he felt compelled to, instead of settling into the comfortable drudgery that most of us do. Late in his stay in Alaska, he learned a painful lesson that ran against the grain of his solitary wandering—that happiness is meaningless if it is not shared. Next to an inspiring passage from Doctor Zhivago (one of a handful of paperbacks he annotated and highlighted), he wrote in all caps, “HAPPINESS ONLY REAL WHEN SHARED.” He died alone, geographically and psychologically isolated from the family that he had abandoned, the old acquaintances that he had shunned, and the strangers which had become fast friends during his journey.

There is little use in defending McCandless after Krakauer’s unabashed apologetic. He defends Chris’s life choices, his underdeveloped skill set, and his burning desire to escape the modern world and his parents. While I don’t know if I agree with Krakauer’s assessment in its entirety, I am inspired by McCandless because he was boldly himself, which is more than many people in our modern age can say. His philosophy may not have been robust or entirely defensible, but he lived it. He went on adventures that many people fantasize about. He lived in willful solitude like a monk, to the endless fascination of Krakauer, who spends some time considering whether or not McCandless was a virgin, and ends the book with the line “Chris McCandless was at peace, serene as a monk gone to God.” Compared to Sean Penn’s film version—in which McCandless is like a rambling apostle, having extremely profound effects on those he encounters, and suffering the death of a martyr in Alaska—Krakauer doesn’t ignore the man’s shortcomings. He presents the negative aspects of McCandless’s story, even though he remains firmly in McCandless’s corner.

One of the most intriguing things about the book is its structure. It is no secret that McCandless dies at the end, and so it can’t build up to a climax of his final days (and that would be weird anyway). Krakauer jumps around nonlinearly, filling in gaps of McCandless’s history, from college, post-graduation, childhood, and highschool years. He includes relevant histories of Chris’s parents, other idealistic freebooters and adventurers. Krakauer’s verbosity keeps the narrative moving forward as the sections overlap to form a cohesive whole. He uses some obscure words as well as some climbing jargon, but keeps things flowing nicely and they is never overly distracting.

Epigraphs from various sources begin each chapter, and quite a few works are referenced throughout: G.K. Chesterton, Tolstoy’s War & Peace and Family Happiness, The Call of the Wild, Walden, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Doctor Zhivago, among others. These are sometimes followed by a note that McCandless had highlighted the passage or scrawled a note in the margins, but some others appear to be from Krakauer’s own library.

To me, the story of Christopher McCandless is inspiring. While I don’t necessarily agree with his purposeful isolation (he actually died very close to civilization, because he chose not to take a map with him), his anti-materialistic and self-sufficient mentality are admirable. When I embarked on my own post-college odyssey—hiking the Appalachian Trail with my brother—I think I felt some of the same promptings that McCandless did, and reading this book evokes many memories for me. We were never in serious peril (because we planned our hike, and the trail was generally well marked), but we did come to know the freedom and confidence that accompany the realization that we could endure without many of the modern conveniences we had become accustomed to throughout our lives. I won’t be joining the cult of McCandless, but I admire his courage.

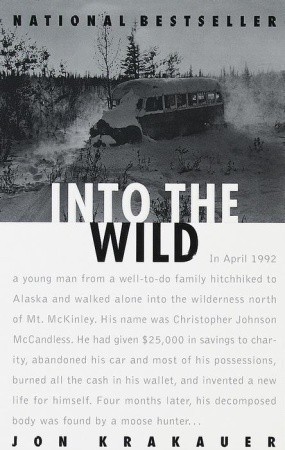

1. The abandoned 1940s International Harvester (AKA “The Magic Bus”) which was McCandless’s base during his fateful summer has become a pilgrimage site for some, and the treacherous route to it has proved fatal for several underprepared pilgrims. UPDATE: In June 2020, the Magic Bus was airlifted out of the Alaskan wild by the National Guard.

Sources:

Levenson, Michael. “‘Into the Wild’ Bus, Seen as a Danger, Is Airlifted From the Alaskan Wild”. The New York Times. 19 June 2020.