“You’re so much better off just playing what you play.”

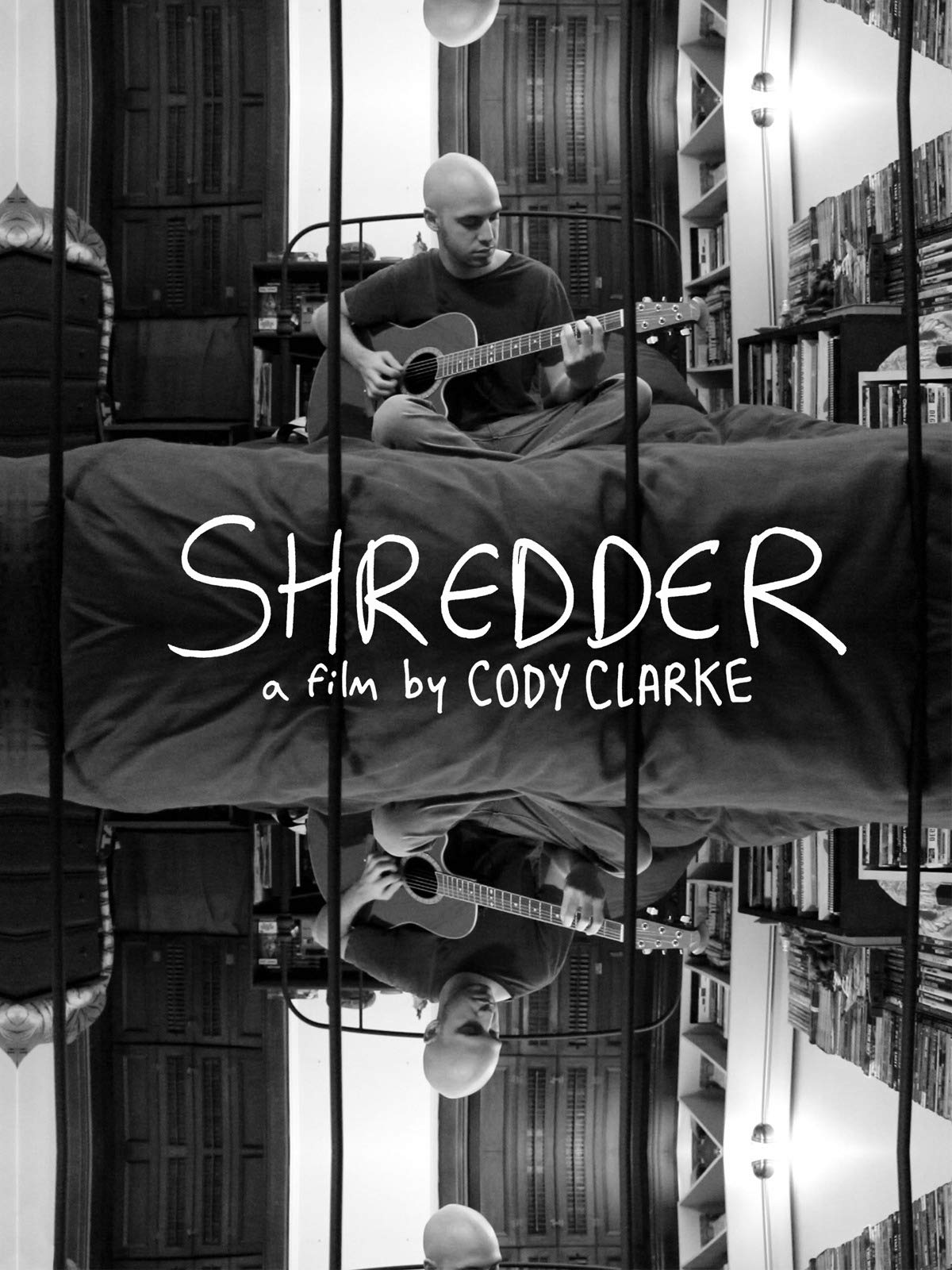

First-time director Cody Clarke, who literally wrote the book on the truly independent filmmaking movement, can be seen here tentatively dipping his toes into all facets of the craft. Clarke’s simultaneous wearing of so many different hats means many aspects of Shredder feel underdeveloped. But this is not unexpected of a debut where a single person has his hands on so many diverse elements. In a Hollywood film, or even an “indie,” everything from script to wardrobe and makeup to cinematography has at least one, if not a team of professionals responsible for it. But for Clarke, too much of the joy of artistic creation comes from the freedom of being able to stand behind each and every bit of his own film. And so while I found Shredder to be flawed and spotty, I also can’t help but admire the audacity to just go out and make a film. It’s a mediocre one, but he got it made and has carried all the lessons forward into his subsequent projects.

The narrative concerns a young man named Travis (Clarke), a laughably amateur musician who whips up some basic chord progressions and crude lyrics about belly buttons and has gradually grown out of his fascination with songwriting. But then, he discovers that his girlfriend’s younger brother is a virtuoso and the two begin a warped relationship by exchanging musical knowledge. There’s a light conflict in ideologies between Travis’s college friend, who tells him to play a kind of inspired style, where whatever comes out is authentic; and the virtuoso, who encourages a thorough reading of a stack of music theory books. But the real conflict lies between Travis and his girlfriend Sarah (Ellie Aaron), who knows some startling things about her younger brother and doesn’t trust him. This causes a rift to grow between the couple that is finally brought to a dramatic head near the conclusion.

Part of the charm of Shredder is it’s conversational quality. As the film’s central character, Travis is in almost every shot, drifting in and out of half-engaged conversations with would-be lovers and would-be friends, only occasionally having a moment of connection but willing to try time and again. If I had to guess, I’d say Clarke used the tried-and-true writer’s trick of mining real conversations for dialogue. It was clearly written rather than improvised, as there are a few evident flubs that were left in the final cut where a cast member had to restart a line. (That’s not a complaint, by the way. Such an approach has led to some very good moments in cinema, notably a few instances in Pulp Fiction.)

I think what will throw most potential viewers off is how emotionally steady the film remains. As Travis meanders about his various relationships—including two more maybe girlfriends, portrayed by Emelia Benoit-Lavelle and Jillene Ansanetta—there is an intentional dearth of forced drama. Most of these conversations, like most conversations in our own lives, pick up somewhere in the middle of a relationship, add a modicum of new meaning to it, and end without a clear resolution. This even-keeled approach is slightly disrupted (in a good way) by the film’s plentiful musical moments. A number of cast members get a chance to play a song or two, and the film’s sole non-Travis-centric scene involves a handful of people playing at a private open mic night.

Because Clarke was doing so many different things, and specifically featured so heavily as Travis, his cinematography was understandably basic. Every shot (unless I missed one or two) was static, though he does have an eye for placing his camera. This is unconventional in modern times, but Ozu and Tarkovsky and others used it to great effect and the style has recently seen revival in the hands of Steve McQueen. Clarke’s not close to that level, but he’s also working with a budget that wouldn’t even pay for the lead’s hairdresser in a Hollywood film. The best shot in Shredder occurs after the open mic night and has five cast members situated on camera. An entire conversation plays out in which Travis loses out on a romantic pursuit to Jake (Rob Goldstein), who wows with his guitar knowledge over the course of three minutes of unbroken footage.

It’s clear that Clarke was an amateur when constructing Shredder, but that’s part of what makes it fun to watch. In this new world of virtually costless films, we are privy to the development process of moviemakers where previously we would only get to see their first big project (for instance, most people who profess love for Nolan have never heard of, let alone seen, Following; same goes for Peter Jackson and Bad Taste, Tobe Hooper and Eggshells, etc.). To see Clarke as a filmmaking infant is exciting and encouraging to me, even though I would think that the average moviegoer would chafe at seeing the growing pains that directors must go through before they can produce something dependable. In my opinion, I treat these early “folk films” like I do the artifacts of the Lumière brothers or Georges Méliès—we’re not looking at masterpieces, but we’re looking at something new.