“If I show weakness, if I retreat, I may be hurt, I may be killed. I must hold my own if I’m gonna stay within this land. For once there is weakness they will exploit it, they will take me out, they will decapitate me, they will chop me into bits and pieces—I’m dead.”

Timothy Treadwell was fond of telling the grizzly bears of Alaska that he loved them. In a desperate childlike voice he would utter the words of affection three or four times in succession. A self-styled “protector” of the ferocious beasts, he spent thirteen summers in the wilderness living among the bears and documenting them, ostensibly on the lookout for poachers. He believed that he had gained the trust of some younger bears that he had known since they were cubs and frequently approached and made physical contact with them. He even gave them names Jane Goodall style, like Mr. Chocolate, Rowdy, and Saturn. Alone on all but a few of the trips, with only a camera for company, he captured hundreds of hours of footage. He was bold to the point of naivety and amassed a stunning collection of intimate and breathtaking moments—not just of himself with the bears (he was quite fond of being on camera), but of grizzlies in their natural habitat—swimming, hunting, fighting. In his own words, “everything about them is perfect.” Treadwell and his girlfriend Amie Huguenard were mauled to death and eaten by a rogue grizzly in October 2003.

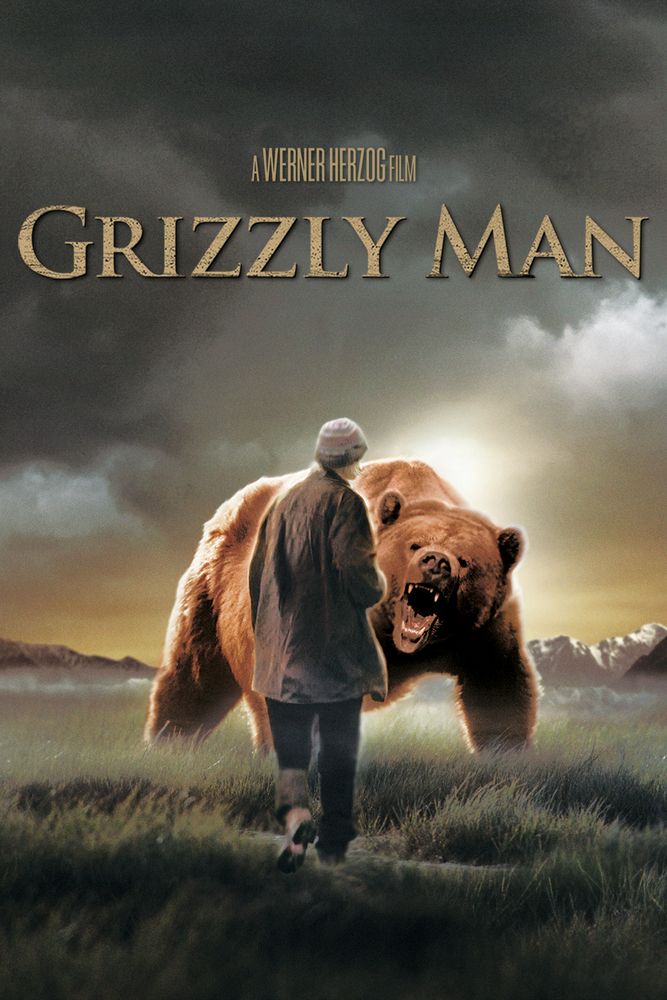

With tenderness and sharp insight, Werner Herzog assembles Treadwell’s footage along with home videos, interviews with friends, lovers, park rangers, bush pilots, naturalists, and coroners—not to make the wildlife advocacy documentary that Treadwell had envisioned, but rather a compassionate portrait of the eccentric man’s life, activism, hinterland exploits, and untimely death. A chance encounter led to Herzog’s involvement with the project and I tend to think that he saw a kindred spirit in Treadwell, someone with more than a touch of the madness that has driven the filmmaker throughout his career. Herzog has frequently put himself in danger in service of capturing transcendent human experience and the wonders of nature. Like Treadwell, who drew the ire of the National Park Service throughout his time in Alaska and collected a handful of violations to his name, Herzog isn’t fond of rules. He has been imprisoned and beaten, risked his life on numerous occasions, and frequently ignored the regulations with his guerilla tactics.

That sense of kinship as both a filmmaker and an explorer lends weight to Herzog’s editing choices and extensive narration. In lesser hands, Herzog’s decision to wrest narrative control from Treadwell might seem quite callous. And not only does he move away from Treadwell’s hobby horse but he does not even create a cohesive narrative of the man’s life! Rather, he constructs the documentary loosely to match the scattered incoherence of Treadwell’s beliefs and motives, never shying away from the warts and peculiarities that made him such a divisive figure. However, by shifting the emphasis of the conservation from the grizzlies—which, it turns out, were never quite in dire straits as Treadwell believed—to the man’s unconventional life, Herzog gets to the heart of the man’s struggles with alienation, self-perception, women, God, and minor celebrity.

And what haunts me is that in all the faces of all the bears that Treadwell ever filmed, I discover no kinship, no understanding, no mercy. I see only the overwhelming indifference of nature. To me, there is no such thing as a secret world of the bears. And this blank stare speaks only of a half-bored interest in food. But for Timothy Treadwell, this bear was a friend, a savior.

Treadwell would often shoot multiple takes, commentate on his own acting abilities, and describe to the camera how he envisioned his show taking shape (predating the survival shows that would become very popular about a decade later). In a way, his isolated life was a sham because he always envisioned himself as the hero of his own story which would be viewed by millions on television. Herzog lets this play out, lingering on moments when a train of thought takes Treadwell into vulnerable territory or when he uses the camera to record an audio-video journal entry. In one of these poignant scenes, Treadwell begins his monologue by referring to God and then clarifying that he does not know whether or not God exists. But by the end of his stream-of-consciousness spiel he has broken down. He’s almost in tears as he thanks God for creating his beloved animals and giving him a purpose to which he could devote his life.

The film’s most powerful moment comes when Herzog is exposed to the final footage Treadwell captured. As the doc expands its scope and moves forward and backward in time, we’re shown pictures of his arrival in summer 2003, self-captured footage from ten days before his death, then three, then mere hours prior. That the camera was running when Treadwell and Huguenard were killed implies that he was intrigued by the encounter, that he was planning to capture the fortuitous moment as he always had. That he never had the chance to remove the lens cap implies that the confrontation turned ugly in an instant. The audience does not hear these final moments. But Herzog does, sitting in the living room of Jewel Palovak, a former girlfriend of Treadwell’s and co-founder of his organization Grizzly People. The encounter had been described for us already by a bush pilot and by a coroner, but as Herzog listens, Peter Zeitlinger adjusts his lens from Jewel’s bewildered face to Herzog, whose fingers are trembling as they pinch back tears. “Jewel, you must never listen to this,” he says. “And you must never look at the photos that I’ve seen at the coroner’s office.” He then hands the tape to her and says, “You should not keep it. You should destroy it. Because it will be a white elephant in your room all your life.” He then cuts to stunning footage of two males fighting for mating rights to emphasize the awesome destructive power of the grizzly. In this way he respectfully avoids making a spectacle of the moment of death but conveys its shocking and gruesome nature.

Sadly, Treadwell’s plight was largely imagined as poachers simply were not a persistent threat to the bears (the closest encounter he captures is some fishermen tossing a rock at one of the bears that is wandering too close to their party). In reality, Treadwell found in the wilderness a chance to escape his past as an alcoholic and a failed actor. This assembled footage, then, does not document a legitimate effort to protect bears. Rather, it conveys the man’s veiled desire to join the bears in their simpler way of life and to live out a fantasy of becoming a movie star. He claims he can speak the language of the bears, constantly plays with his blonde locks, and creates a fictional conflict in which he will act as the knight in shining armor, without anyone around to pop his fantastical bubble—except the bears themselves.

Despite his constant assertions of the incredible risk of his venture, Treadwell never acts as if he’s in danger. He will approach the bears, swim next to them, and turn his back to them. He believed he had worked his way into their hierarchy and asserted himself as a dominant presence. As one interviewee puts it, “He treated them like people in bear costumes.” There was a scene in the theatrical release, replaced for the DVD version, of Treadwell making an appearance on Letterman. The host makes an offhand joke about a future newspaper headline that informs readers that Treadwell has been eaten by a bear. Treadwell laughs it off and the conversation moves on. It was probably this lunatic idealism that finally did him in. The contrast between Treadwell’s rambling self-commentary and Herzog’s bleak narration which critically assesses the man’s fantasy brings into focus the director’s favorite topic—human nature. As an idealistic visionary toppled by hubris and delusion, Treadwell proves a perfect subject.