“You gotta keep your bodies off each other unless you intend love.”

Did anyone have a good time at the Altamont Speedway Free Festival? You wouldn’t think so, going by the show’s depiction in Gimme Shelter. Directed by Albert and David Maysles along with Charlotte Zwerin, the concert doc builds up to the ill-fated “Woodstock West” by surveying the droves of pagan pilgrims, three hundred thousand strong, with all their tight pants and denim jackets, sunglasses and bandanas, eyeliner and long hair. Some are on drugs and flail around in the straw-covered fields. Others are peddling various substances, perched on the periphery, coy and mysterious. A few decide to forego any sort of attire at all and gyrate to the music of the opening acts (Santana, Jefferson Airplane, The Flying Burrito Brothers, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young1) in the nude. An activist ambles around collecting donations for the Black Panther defense fund. One woman, known only secondhand, gives birth. Many more do less notable things, like passing joints and jugs of wine around the bonfire.

To a man, the concert attendees seem drawn to the site by the sheer gravity of the event; they are here to bear witness to history as much as they are to enjoy a rock concert. And that’s to say nothing of the Hells Angels, infamously and mysteriously “hired” for “security,” who are chugging beer and pulping stoned civilians with pool cues and motorcycle chains long before the Rolling Stones start their set or Meredith Hunter bum rushes the stage with a .22 revolver and a central nervous system charged with methamphetamines. Hunter’s death by knife wound is a grim capstone to the disastrous event, as the cinéma vérité camera helplessly looks on from the stage while the ghastly episode unfolds. What, indeed, was the point of all this, other than to undermine the hippie ethos? To once and for all crush the idealistic aspirations of a generation with a heavy dose of human depravity?

The scene of desolation was laid out in a multi-perspective exposé from Rolling Stone magazine which used apocalyptic imagery to mythologize the event; a far cry from the equally mythologized scenes of carefree euphoria on display in Woodstock. Both are symbolic of the ‘60s counter culture, but Gimme Shelter doesn’t smear a romantic gloss over its acres of litter and miles of abandoned cars, its bad LSD trips and profusion of injuries; nor does it have the option of concealing the army of technicians, law enforcement officers, medics, and volunteers that made the initial free love spectacle possible, because Altamont didn’t have a similar support system. Iconic images of Woodstock abound, but what better reflection of the tainted ‘60s ethic than a corpulent, buck naked, drug-hazed dropout taking center stage and flopping her body up against the godforsaken stage moments before a black man is stabbed to death amidst a sea of those who would claim peace and harmony as their guiding principles? In the words of Mick Jagger, who tries and fails to dodge and strut his way around the brewing catastrophe, “Why can’t everybody just cool out?” Unfortunately, the Stones were better at getting a crowd riled up than they were at calming them down.

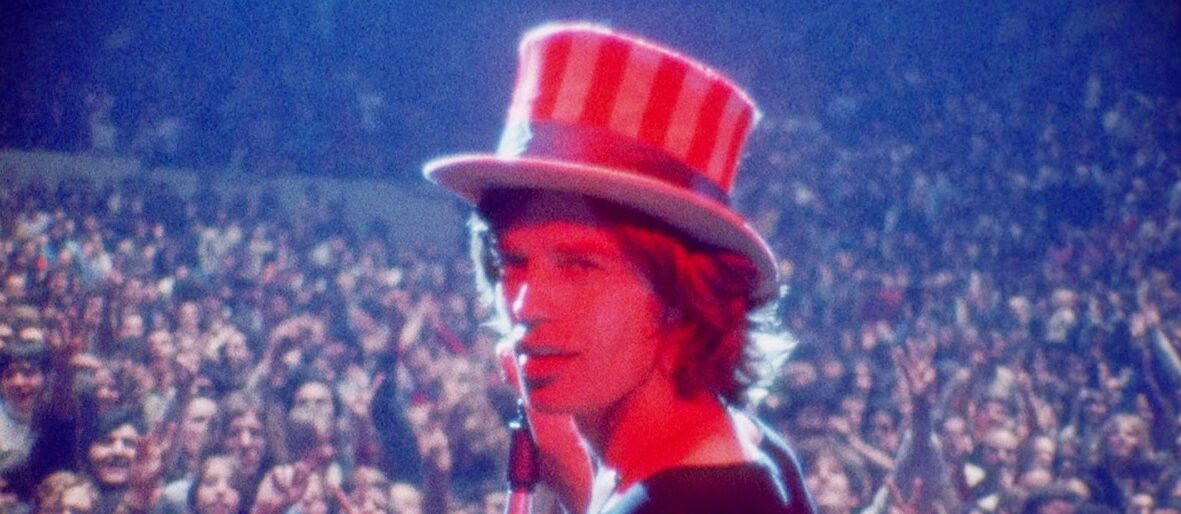

The sense of impending doom is partially allayed by some brilliant footage of an earlier Madison Square Garden show with Ike and Tina Turner (the same show that became Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out!), the Altamont set itself, and some cool rock ‘n’ roll iconography—Keith Richards leaned back and zoned out at Muscle Shoals studio, his snakeskin boots propped up, completely tranquil, listening to ‘Wild Horses’ along with his bandmates; X-factor Mick Taylor stashing his smoldering cigarette on his guitar’s headstock; Mick Jagger in his Uncle Sam top hat; the rose-tinted, slow motion camerawork during ‘Love in Vain’. This was the Stones at the heights of their powers and popularity, the greatest rock ‘n’ roll band in the world, smack in the middle of their golden four-album run (Beggars Banquet, Let It Bleed, Sticky Fingers, Exile on Main St.), before Zombie Kief and decades self-parody lessened their bite,2 blithely fumbling their own self-arranged coronation as Jagger’s manufactured posturing as a kinetic rabble rouser led to real violence; a drug-fueled hippie liturgy transformed into a sacrifice to Moloch.

Indeed, the film, which unfolds out-of-order, always tempers its hagiography. The Maysles seemed to intuit the disaster before it happened and studiously employed numerous cameraman (including a young George Lucas) and sound technicians to capture the the slick, sloppy dealmaking by lawyer Melvin Belli (memorably portrayed by Brian Cox in David Fincher’s Zodiac), the Stones’ cult of celebrity, the unchecked drug use, the brewing violence, and used those details to slowly build a sense of dread and inevitable tragedy. The film is so effective that Pauline Kael all but accused the filmmakers of staging the murder themselves. It does have the scent of a snuff film about it—how could a concert film retroactively shaped around an unexpected murder caught on camera not?—but there’s no attempt to abdicate or vilify the Stones, the Angels, or Hunter beyond the footage itself. And the question of who profits from the film is ultimately much less interesting than examining the film as a historical document. As it concludes with Jagger watching footage of the tragedy on a Moviola, like an Orson Welles “movie within a movie,” the audience, like the singer, is left feeling hollow, shell-shocked, vulnerable—or is the consummate showman still performing? For all it does intentionally, the enduring luster of Gimme Shelter lies in its inability to contain itself; in its unquantifiable impact on the events it is documenting and the questions it raises about art and morality and the limited truth-telling capabilities of cinema. Godfrey Cheshire’s comparison to Abbas Kiarostami’s Close-Up is apt.

The Mỹ Lai massacre and the Manson murders had been building toward a menacing culmination, and for many, Altamont was the final nail in the coffin; the illusion of peace, love, and sexual promiscuity had been totally dispelled. The Stones survived, in some sense, but the ‘60s didn’t. “Faith has been broken, tears must be cried.”

1. The Grateful Dead were also on the schedule but pulled out due to the brewing sense of violence.

2. They still put on a great show when I saw them for the first time in 2015.