“We’re too much ourselves. Afraid of letting go of what we are, in case we are nothing, and holding on so tight, we lose everything else.”

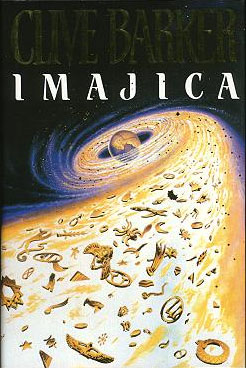

Sprawling, imaginative, uncategorizable, and oftentimes downright perverse, Clive Barker’s Imajica is an opus I’ve revisited twice within the span of only a few years, each time seeking to further comprehend its allure, and each time reverting to head-scratching wonder.

A handful of individual elements hook me: a convincing fantasy world that is both expansive and coherent; a multitude of inspired deviations from reality that gradually build on one another as they transport the reader from modern day London and New York to the twisted realm of the Imajica (a portmanteau of “imagination” and “magic”?); a palpable sense that untold mysteries are lingering on the periphery of our everyday experience; multiple characters with sufficient depth, diversity, and development to carry a lengthy narrative; numerous minor characters with memorable traits and distinct personalities; a verbose and scrupulous writing style that simultaneously provides an abundance of detail and yet describes the richest of its exotic creations with a gratifying lack of clarity; a commitment to enthrall with its particulars (secret societies, parallel universes, assassinations, astral projection, Boschean grotesques, doppelgängers, magical cities, divine pantheons) as it goes about exploring consequential themes (God, the fall of man, love, sex, gender, death, oblivion) with an utter lack of sanctimony.

I think that last bit may be the key, or at least one of them—that Barker remains resolutely unruffled by the radical impulses that inform his dreamlike narrative (which he suggests was literally fashioned from his own dreams), which in turn renders the reader receptive to even his most freakish ideas. In this way, he’s able to reveal, about halfway through the book, that Jesus Christ and God the Father exist within the Imajica in a state of distortion and corruption; that “Christos/Jesu” was one of many failed messiahs while “Hapexamendios” devolved into cynical self-obsession in the eons since he created the Five Dominions. Including actual religious figures in fantasy (let alone twisting them in the depiction) is always a dicey proposition, but Barker is so earnest in his impassioned approach that a Christian can read it and comprehend that its deviations from the created order reflect the confusions of an inquisitive mind rather than the resentments of a committed heathen. As Francis Schaeffer points out in He Is There and He Is Not Silent, the Christian need not be existentially confused by fantasies and dreams and is thus free to marvel at them, even and especially where they diverge from reality.

While the righteousness of The Lord of the Rings is absent, so is its opposite, leaving characters to flounder as they search for a larger purpose. They find numerous divine beings in their midst to which they might submit their wills, but because there’s no moral clarity or superiority, Barker is able to explore the dynamics between humans and gods/demons through a lens of wonder rather than telegraphing his twists by setting up an explicit good vs. evil dichotomy (even if the broader narrative structure follows the hero’s journey). This effect is compounded by capricious and stubborn characters who change their minds, experience life-altering revelations, and try to shift fate through sheer force of will.

Another elusive facet of Imajica stems from two of its central characters, Gentle and Judith, who begin the book with truncated memories of their lives, only capable of remembering a handful of years into the past. Both of them lead more or less ordinary existences in modern day civilization without any knowledge of the other four Dominions or Hapexamendios or the In Ovo or Nisi Nirvana or the Ana or the Tabula Rasa or Patoshqua or the Erasure or Tishalulle or Yzordderrex or Uma Umagammagi. But as the plot unfolds, we realize along with these characters just how intimately connected they are with a narrative that spans millennia and concerns the fate of all creation. They are initially reacquainted with this magical peripheral world by Pie ‘oh’ Pah, a shape-shifting androgyne who serves as a continual catalyst for unlocking their memories and leads Gentle on a pilgrimage of self-discovery across the Imajica. Gentle, a messiah figure tasked with reconciling the Dominions by magical rites (though it takes him most of the book to realize it), who begins the novel as a louche playboy/master forger of paintings, is constantly on the verge of revelation as he encounters vaguely familiar people and places, memories of which are buried deep within his subconscious. In effect, while reading the book, I was frequently struck by sequences that called to mind the fever dream hallucination in Paul Thomas Anderson’s film Phantom Thread, in which Daniel Day Lewis’s febrile dressmaker conjures an evanescent vision of his dead mother as a young woman—a desperate, transcendent illusion brought on by his delirious state. Barker’s setup gives him frequent opportunities for such numinous interactions, and his routine success in writing them imbues Imajica with a sublime spiritual quality, culminating in a heartrending glimmer of hope that we may be finally reconciled to those whom death has stolen away.

Though lightweights might dislike its bloated size and ruminative style; though puritans might scoff at its questionable depictions of God; though prudes might cry foul at its raw violence and psycho-sexual kinks; few fantasy books can match the sincerity, scope, and unbridled imagination of Imajica. I’m happy to count it among my favorites.