“Darkness and cold, darkness and cold,

Rolled in through the holes in the stories I told.”

“I always said we would stop before we got bad,” David Berman wrote when he announced the breakup of Silver Jews following the tepid reception to their final album, 2008’s Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea. Berman left the music industry entirely and became something of a recluse. He spent his time reading books while his guitar and vocal chords collected dust. Initially, there was a blog with occasional poetry, essays, photography, and whatever caught his fancy. But as the years progressed his public presence dwindled considerably.

It was during this decade-long hiatus that I discovered Silver Jews, immediately latching onto the songwriter’s deadpan baritone and depressive, darkly humorous lyrics. His lackadaisical drawl and sardonic worldview became a part of my mental health routine as I was trying to figure life out during college (I still haven’t succeeded, by the way). American Water became a quick favorite of mine and was in steady rotation on my headphones as I wandered about the Pitt campus and trekked a mile each way to and from my apartment. I was taken by Berman’s gallows humor and the laid back, slow-rocking twang of his band’s music.

You could tell he wrote his songs as a kind of cathartic self-exploration, as if the act of creating them helped him keep his head above water. The music was suitably loose and homespun, unconcerned with the slick, manufactured sonic palate of the mainstream. Catering to the masses was not a live option for Berman; selling out would have gone against his nature and probably been more depressing than seeing his albums fail to get attention. All that to say, I was drawn to the aesthetic and the musical simplicity, but also resigned to the fact that this tortured poet was done writing songs.

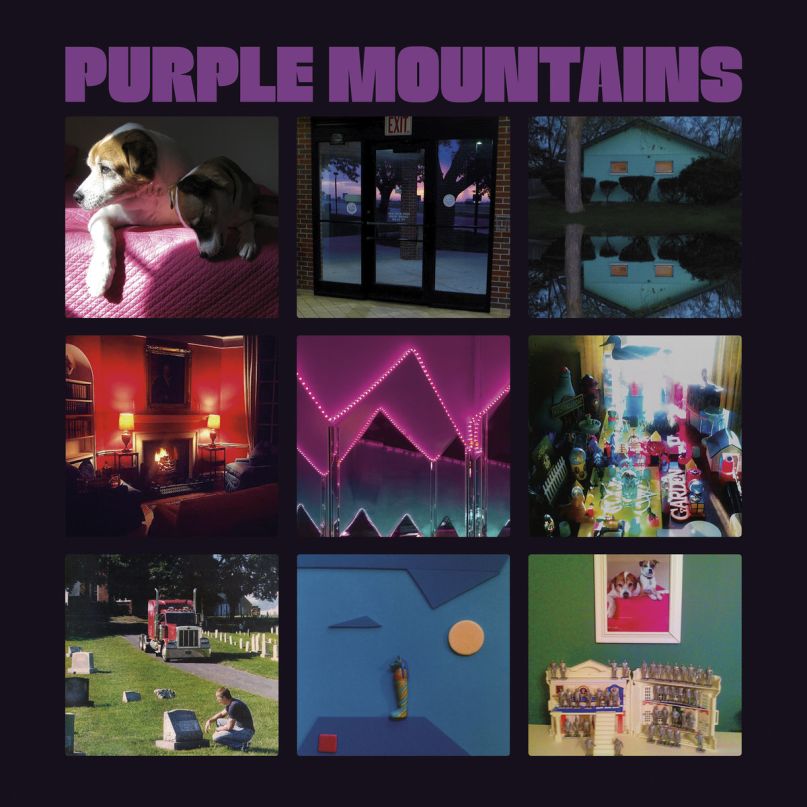

In 2019, I was settling into a new job, renovating my first house, and preparing for marriage—I didn’t have time for keeping up with the music world. I didn’t even know that Purple Mountains had been released two weeks before my wedding. When I finally learned, in early 2020, that Berman had released new music after “a decade playing chicken with oblivion,” what should have been a happy day was instead one of grief. David Berman had taken his own life less than a month after the releasing his comeback album. A tour had been scheduled and he was poised to assume his mantle as a grandfather of outsider indie rock. But then the future was gone. Sideswiped by the news, I had almost no desire to listen to the album. Knowing Berman’s penchant for self-deprecation, his history with substance abuse and a previous unsuccessful suicide attempt, I wasn’t prepared for the emotional weight that was sure to burden this album. I knew it would not be a healthy choice for me to subject myself to that until I distanced myself from the news of his death, and so I gave myself a few months to process things.

The proximity of the album release and his death makes it particularly troubling, as if he held on simply long enough for it to see the light of day, like David Bowie’s Blackstar, Leonard Cohen’s You Want It Darker, or Warren Zevon’s The Wind. In those cases, though, the artists were taken from the world by disease. Of course, depression sometimes feels that way too. It’s not like depressed people choose it; they’d will their way out of it if they could. That Berman took his own life casts a harrowing shadow over the entire project and gives us a tainted lens through which his typically self-effacing lyrics crystallize for us into painfully sharp observations of sadness, regret, and pity.

It may have always seemed like Berman was barely hanging onto his will to live, but listening to his ruminations on Purple Mountains, it’s a wonder that he could even work up the gumption to pick up a guitar and strum out a few chords before pulling the sash cord on life’s final curtain. It’s a downright painful record to listen to. One that makes you “feel” deeply, whatever that means. I think a part of my reluctance to listen to the album was tied up in a fear that he had “cashed in,” and that Purple Mountains would indeed be that bad album he had quit Silver Jews to avoid, and that his legacy would be marred. But it’s neck and neck with the best records the man ever made. It is a sad conundrum that has no solution.

There had been rumors of comebacks throughout the years, but nothing very serious. There’s a scrap bin that contains collaborative efforts with Dan Bejar of Destroyer and another with discarded demos with friend and former bandmate Stephem Malkmus. But it was the death of Berman’s mother in 2014 that sparked him creatively, resulting in the heartfelt ‘I Loved Being My Mother’s Son’. He eventually teamed up with Jeremy Earl and Jarvis Taveniere of the psychedelic indie folk band Woods, who handled production duties and added some drums and guitar.

I can barely bring myself to dig into the songs from a critical perspective. Some of them achieve Berman’s signature blend of pleasant chord progressions countered by his baritone drawl and wry self-effacement. The opener, ‘That’s Just the Way That I Feel’, features cynically humorous couplets like “When I try to drown my thoughts in gin/I find my worst ideas know how to swim.” An early highlight, ‘All My Happiness Is Gone’, is bookended with arrhythmic strumming and humming, while the song proper is a Mellotron-driven downer about the loss of meaningful friendships as one grows older.

Friends are warmer than gold when you’re old.

And keeping them is harder than you might suppose.

Lately, I tend to make strangers wherever I go.

Some of them were once people I was happy to know.

‘Darkness and Cold’ and ‘She’s Making Friends, I’m Turning Stranger’ both analyze the dissolution of Berman’s marriage to his wife Cassie and showcase Berman’s trademark lyrical sleight of hand, combining various turns of phrase to conjure new meanings. Amidst the twangy folk rock, Berman’s inevitable pain is palpable. Their separation was apparently amicable, but it’s still nearly impossible to conceive that a person with whom you’ve been exclusively romantically linked for several decades will now be seeing other people. While Berman remained holed up with his mounting pile of books, scoured the internet for novel views on art and the act of creation, intermittently blogged, and grew increasingly reclusive, his former wife’s social life was blossoming. “The light of my life is going out tonight with someone she just met,” he sings.

The most devastating stretch of the album is the one-two punch of ‘I Loved Being My Mother’s Son’ and ‘Nights That Won’t Happen’. The former, as mentioned and is evident by its title, is a poetic rumination on the death of Berman’s mother. It’s neither musically nor lyrically sophisticated. It reminisces on his mother’s support during his childhood trials and triumphs, culminating in a brutal verse where he confesses, “I wasn’t done being my mother’s son.” It’s the kind of song that, in the hands of a self-serious artist who thought highly of themselves, would sound incredibly sappy and lame. But Berman couldn’t be anything but earnest and so the simplicity works. Following this is ‘Nights That Won’t Happen’, a meditation on death and the philosophical conception of suffering. Knowing how the story ends, this song becomes a very chilling look into Berman’s psyche. As much as the entire album reads like a confused suicide note, this song encapsulates Berman’s coming to peaceful terms with death the most clearly.

The dead know what they’re doing when they leave this world behind,

When the here and the hereafter momentarily align.

Berman really was a one-of-a-kind songwriter. He stared into the abyss and always seemed to come out of the other side of it with a cynical smile and a handful of songs that acted as a balm for those similarly afflicted but less talented. His records will last for a long time, but with the man himself now departed, there is certainly a mental shift in how one views his music. I’ve thought for a while about who can fill this unique void he has left. Labelmates Bill Callahan (Smog) and Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy occasionally tread in similarly depressive territory, but I don’t think they really fit. Perhaps the best comparison for Berman’s death-saturated final album is the recent output of Phil Elverum, whose Mount Eerie albums, beginning with 2017’s A Crow Looked at Me, have been an extended process of dealing with the early death of his wife Geneviève. There may be other bands that Silver Jews inspired that hew even closer to Berman’s style; but for me, Silver Jews was always enough to meet that need.

Way deep down at some substratum,

Feels like something really wrong has happened.

And I confess I’m barely hanging on.

Many fellow musicians have come out of the woodwork to pay him tribute, but his death is just as affecting for those who’ve spent years with his creaky baritone musings soundtracking their lives. It’s a real testament to the mysterious power of music and words that the death of someone you never knew can feel like the death of an old friend. Would it have been any more or less sad if he had met his end without completing Purple Mountains? I don’t know. Is it any less sad that untalented people take their lives every day? Without falling off a cliff of psychoanalysis, suffice to say that Berman’s final endeavor is one of great sadness, but despite the complicated emotions that have resulted from his subsequent death, it’s also one of great beauty. Whys and what-ifs will swirl around the minds of his devoted fans for a long time. We’ll look for clues in music that’s been saturated with depression since his first release. We’ll wonder if a letter from a fan could have made a difference. But the past is fixed, and as is usually the case in situations such as this one, it’s healthier to celebrate the departed even amidst the mourning. To Berman, life was impossible, strange, haunting, and beautiful; his final self-portrait is a harrowing reflection of that jaded worldview.

Favorite Tracks: All My Happiness Is Gone; Darkness and Cold; She’s Making Friends, I’m Turning Stranger; I Loved Being My Mother’s Son; Nights That Won’t Happen.

Sources:

Kavanagh, Adalena. “An Interview with David Berman”. The Believer. 31 January 2020.

Berman, David (under the username DCB). “Silver Jews End-Lead Singer Bids his Well-Wishers Adieu”. Drag City Forums. 22 January 2009. (Archived).