“Folks hold their prophets to pretty high standards. Even in California.”

Carnivàle makes considerable use of occult elements to bolster its cosmic good vs. evil theme—tarot card divination, Templars, doppelgängers, astral projection, stigmata, spirit possession, resurrection, clairvoyance, telepathy, precognition. It also revels in both its Depression-era Dust Bowl backdrop and its traveling carnival milieu, and is suitably adorned with period attire, props, and music. Indeed, it’s probably enjoyable enough on the merits of its aesthetics and general premise to justify watching its two seasons despite a premature cancellation by HBO. But be assured it’s much more than its aesthetics and premise.

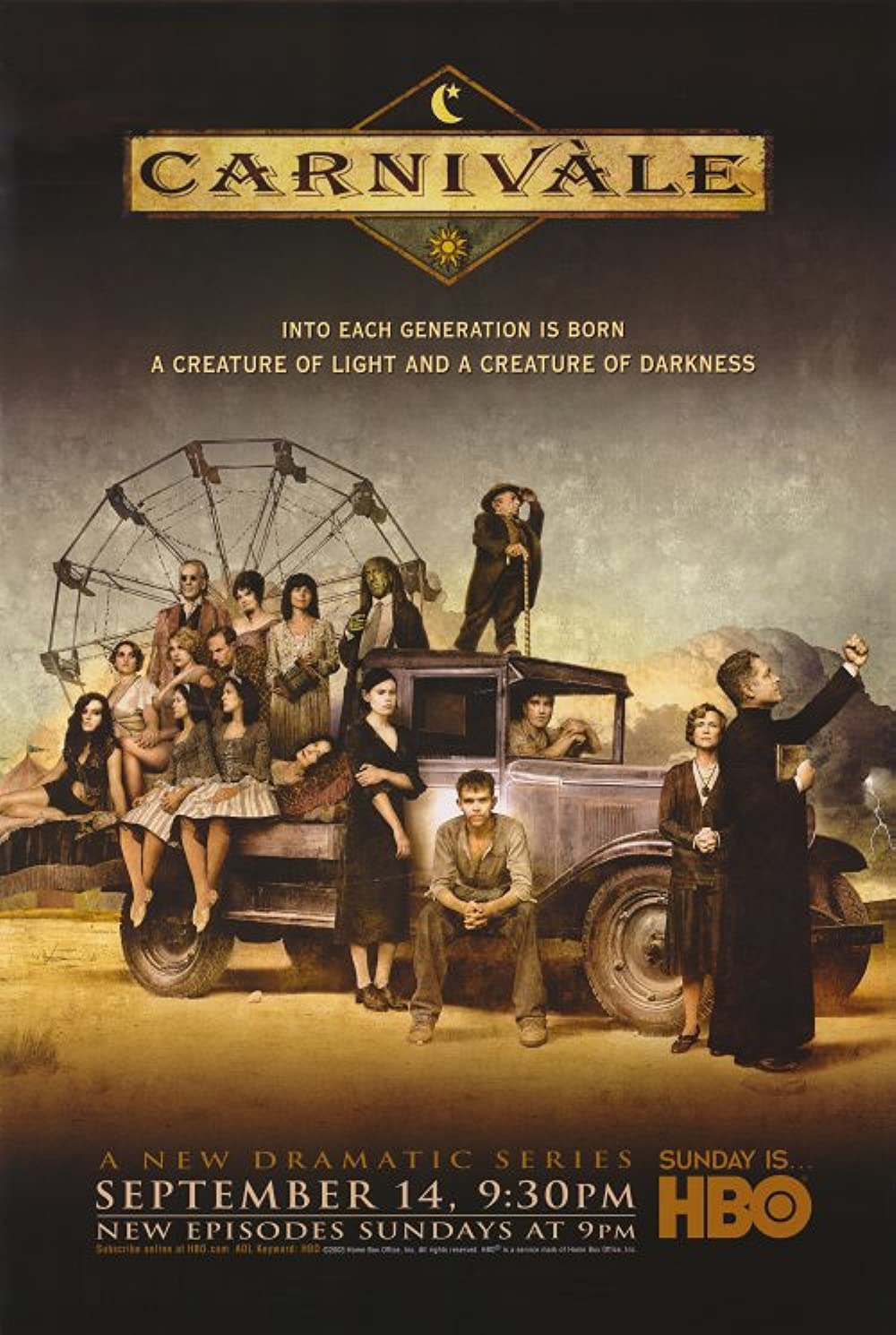

Recalling Tod Browning’s circus-centric silent films (The Unholy Three, The Show, and the notorious Freaks), the show traces the converging storylines of two “avatars”—creature of light Ben Hawkins (Nick Stahl) and creature of darkness Brother Justin Crowe (Clancy Brown)—as they are gradually drawn together by fragmentary, narratively dense visions of future and past events which transgress the boundaries between fiction and reality in a way that strongly evokes David Lynch and Mark Frost’s Twin Peaks.

In the first episode, Hawkins, a taciturn chain gang fugitive, is picked up by a mobile freakshow brimming with odd and intriguing characters, including a fortune teller (Clea DuVall), a gimpy ferris wheel operator (Tim DeKay), a family of stripteasers (Cynthia Ettinger, Carla Gallo, Amanda Aday) headed by a ballyhoo (Toby Huss), a snake charmer (Adrienne Barbeau), a blind mentalist (Patrick Bauchau), a bearded lady (Debra Christofferson), a strongman (Brian Turk), a catatonic psychic (Diane Salinger), a lizard man (John Fleck), conjoined twins (Karyne and Sarah Steben), a giant (Matthew McGrory), and a dwarf showrunner (Michael J. Anderson) who operates under the aegis of a possibly-metaphysical entity. As he spends more time with these impoverished nomadic carnies, who exhibit their own peculiar culture that contrasts with those of the locales they visit, Ben seeks to understand his mysterious ability to give and take life as well as the ghastly visions that haunt his dreams.

Meanwhile, a parallel storyline follows Brother Justin’s rise from the ashes of his charred ministry. After a brief sojourn in a sanitarium, he commences a deceptive radio ministry dubbed “The Church of the Air,” gathering around himself a loyal flock of thousands even as he harbors a literal demon within him. He’s a sinister minister in the mold of Robert Mitchum’s preacher in The Night of the Hunter, except imbued with paranormal powers. His sister Iris (Amy Madigan) remains steadfast in her public support of his ministry, but along with the Reverend Norman (Ralph Waite)—who rescued the siblings when they were orphaned immigrant children wandering in the wilderness—she plots against him. Factoring into the visions of both men is a spiritual feud between elusive characters Scudder (John Savage) and Belyakov (Michael Massee) which suggests that the story’s origins stretch back into the late nineteenth century; maybe even to the beginning of time itself.

In a series saturated with the arcane, mythological, and macabre, the cast of misfits could have easily been rendered as a loose collection of one-dimensional background players used to provide flavor. But with a few exceptions (that might have been rectified in future seasons), these characters prove much more sophisticated than their individual oddities. They’re richly drawn, believably acted, and given sufficiently weighty subplots all their own. Favoring a sparse expositional style, the show only reveals the depth of its ensemble over time as small scenes gradually flesh out the supporting roles. Although some of the side stories are less gracefully integrated as the second season shifts the bulk of its focus to the overarching narrative, the show’s pinnacle (for me anyway) actually comes in a tangential thread in which plain old natural evil is visited upon one of the carnies by a gang of vengeful men. It’s a harrowing sequence that leaves our man in a moribund condition, allowing Hawkins to briefly take on a Christlike aspect when he applies his healing power by channeling life from the buzzards that have been eagerly circling.

Throughout the series, these abundant biblical allusions are layered with cultural references and historical iconography—most notably a vision of the Trinity nuclear test (yet to occur in the show’s timeline) which comes to symbolize the Apocalypse and a stirring opening credits hodgepodge that includes Klan members, dictators, Zeppelins and soup kitchens among its assorted esoterica—to generate a sense of looming psychic dread that remains fecund even after the series’ final episode. (The hypnotic, tour de force credits sequence, which one should only begin skipping after they’ve relished it a good handful of times, goes a long way toward drawing the viewer into the show’s otherworldly, occult-infused historical setting. Read Jean du Verger’s fantastic essay on how the show embeds its fiction in historical reality.)

It’s a shame that the show didn’t attract sufficient viewers for HBO to commit to its expensive production. Knauf had another four seasons planned. Though at times the deliberate abstrusity and convoluted mythology of the first two seasons blunted the impact of its rangy storytelling, it is that very same warped and cracked reality that sets it apart from its peers, and I would gladly have signed up for a few more.