“Every lie we tell incurs a debt to the truth.”

I don’t put it on my résumé anymore, but back in the day I took enough college courses in nuclear engineering to earn a certificate in the field. During our studies, my cohort visited the Breazeale Nuclear Reactor at Penn State, learned to recite several impressive-looking equations full of Greek letters, and one of our number even ended up pursuing a PhD in nuclear science at MIT. Though our curriculum was primarily oriented around the definition and manipulation of variables on a whiteboard, several lectures were dedicated entirely to the discussion of nuclear incidents and accidents and atomic warfare. Three Mile Island was of particular interest due to its proximity to the school, but the Chernobyl disaster merited considerable attention as well.

Though I’ve long since forgotten those equations and never pursued employment in the field, one thing that I have retained from those few semesters of study is that nuclear physics is incredibly difficult for the layman to understand. I could go home and explain thermal expansion or moments of inertia to my grandmother and she’d more or less comprehend it. It jibes with the physical reality she experiences. But fission and fusion are so far beyond the average person’s practical knowledge that explaining it to them is like teaching a dog how to play chess.

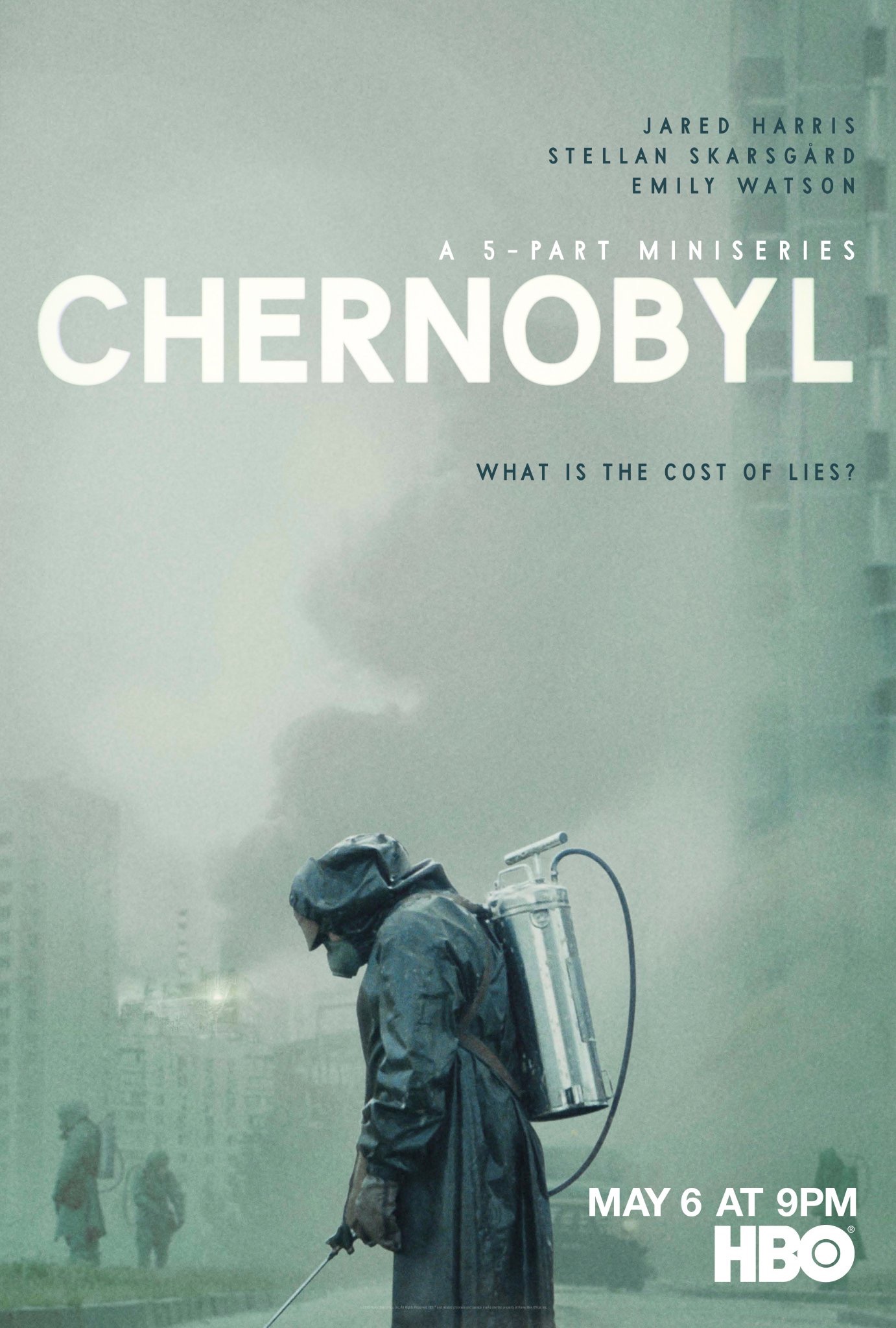

HBO’s Chernobyl, a five-part miniseries which dramatizes the events surrounding the 1986 explosion of an RBMK reactor at the Vladimir Lenin Nuclear Power Plant, wisely does not try to teach a dog how to play chess. Instead, it casts Stellan Skarsgård in the pivotal role of Boris Shcherbina, a journeyman politician tasked with “cleaning up” the incident who quickly finds himself in over his head. As the bleak reality of the situation gains clarity, rather than continue to blindly make decisions simply because he is in a position of authority, he cedes operational control of the situation to Valery Legasov (Jared Harris), deputy director of the Kurchatov Institute, and Ulana Khomyuk (Emily Watson), a nuclear scientist from Minsk who detects radioactivity in her lab hundreds of miles away and intuits what has happened.

After five hours of osmosis, one is bound to soak up enough jargon that Legasov’s courtroom explanation of nuclear power plant operations will land, but the basics of what must be understood are fairly simple: the reactor exploded; the material in the reactor—which is still burning, mind you—is now spreading across the continent in particulate form; contact with it is extremely detrimental to one’s well being. Most people at least understand the last bit (which is why nuclear power has historically been viewed unfavorably by the general public), and writer/producer Craig Mazin and director Johan Renck make use of that kernel of awareness to build out their narrative framework. Around that simple inciting event, we move forward and backward as Shcherbina and Legasov head up containment efforts and Khomyuk interviews the dying control room technicians to understand the course of events that led to disaster. Eventually it arrives at the prosecution of the three men deemed responsible for the disaster—Anatoly Dyatlov (Paul Ritter), Nikolai Fomin (Adrian Rawlins), and Viktor Bryukhanov (Con O’Neill)—and through that Party-controlled process, highlights the opaque bureaucracy that exacerbated the the situation by presenting a curated image to the world.

In many ways, Chernobyl pays tribute to those who risked (and in many cases gave) their lives in order to limit the damage, often with only limited knowledge of the situation. “Do you taste metal?” one of the firefighters asks moments after they notice radioactive chunks of graphite scattered on the ground outside of the burning facility. Even those who don’t make physical contact with the stuff, such as Vasily Ignatenko (Adam Nagaitis), find themselves succumbing to the effects of radiation poisoning. Ignatenko’s wife, Lyudmilla (Jessie Buckley), thinking her husband is merely burned, secretly visits him in the hospital; she only survives because the radiation concentrates in the baby growing in her womb.

At certain points Legasov is forced to request that men be used to complete various tasks that almost certainly dooms them to short lives. They try using helicopters to drop boron and sand on the fires, but an alarming insight from Khomyuck necessitates sending three men into the plant to manually open a series of valves. In order to install a heatsink, hundreds of miners work around the clock to dig a tunnel underneath the reactor. When remote control lunar rovers are destroyed by radiation on the roof of the facility, thousands of men are sent up for 90 seconds at a time to shovel radioactive debris. (There’s an especially pulse-raising sequence on the rooftop that captures one man’s arduous stint in a single long take.) Despite the evident contempt that nearly every authority figure shows for their subordinates, the willingness of the Soviet rank and file to sacrifice their futures for the greater good is underscored many times over. Additional spiritual anguish is derived from a liquidation crew sent out to kill radioactive housepets and the lead-coffin-in-concrete burials of the radioactive saviors, while Hildur Guðnadóttir’s mournful score and Renck’s choice uses of slow motion and barren soundscapes provide appropriate accents to the drama.

“Why worry about something that isn’t going to happen?” KGB deputy chairman Charkov (Alan Williams) asks Legasov in the show’s final episode after a discussion about the future career Legasov has thrown away in the name of the truth. “Ah, that’s perfect,” Legasov responds, realizing the bitter irony in the question. After all, an RBMK reactor cannot explode, so why even consider that it might? “They should put that on our money,” he says. Chernobyl is superlative television across the board, and educational to boot. If you aren’t squeamish it’s well worth your time. Even then, you can avert your gaze when needed.