“Things happen, all according to instincts. There ain’t none… ain’t no distinctions.”

On paper, Tobe Hooper’s Eaten Alive is a logical follow-up to his genre-transforming The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. It is set in the backcountry, it tangles with a sexually-stunted weirdo who gets excited by violence, it is powered by a mad electronic swirl of sounds composed by Hooper and Wayne Bell, and Marilyn Burns spends most of her time on screen in a state of mortal terror. The similarities abound. But on screen, Eaten Alive is something entirely different. Shot on a soundstage bathed in colored lights, it is a complete departure from the gritty verisimilitude and eerie plausibility of the earlier film.

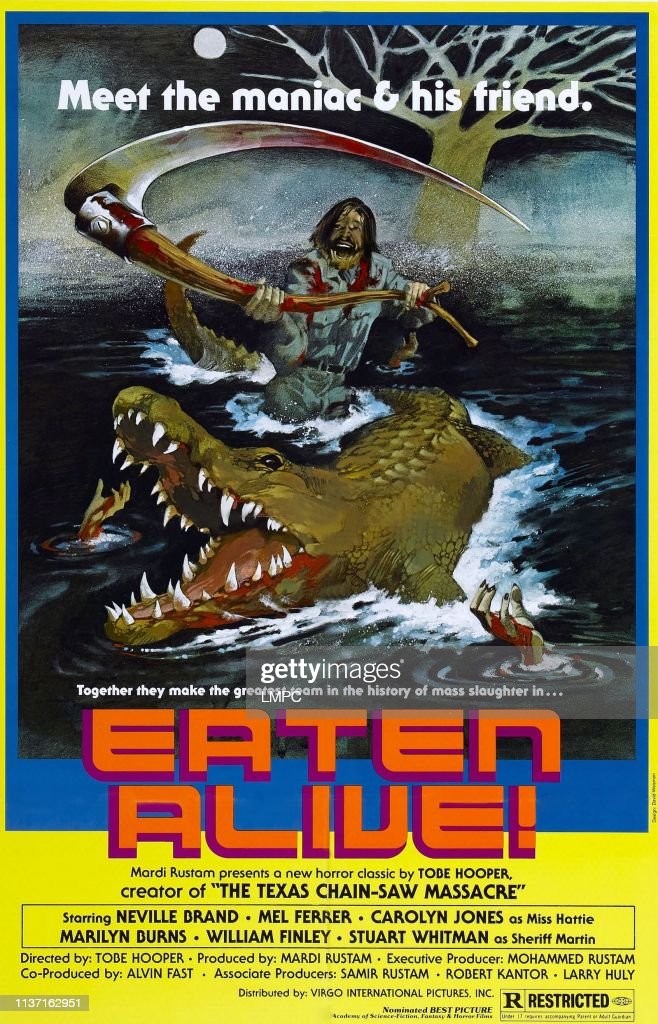

Written by Texas Chainsaw alumnus Kim Henkel (who also worked with Hooper on his experimental indie debut, Eggshells), it thwarts narrative convention at every turn. The film opens on Buck (Robert Englund of Freddy Krueger fame) suggesting to a fledgling prostitute that he’d like to perform an act that rhymes with his name—a line that Tarantino would appropriate for Kill Bill Vol. 1 a couple decades later. He’s with Clara (Roberta Collins), who, it turns out, is not a whore at all, but a naïve runaway who thought she could make a quick dollar working at a brothel. But she chickens out and squirms around so much at Buck’s kinky requests that Miss Hattie (Carolyn Jones) feels obliged to reward Buck with his pick of any two of her best girls. Furious, Miss Hattie sends Clara away. She wanders to the Starlight Hotel, where the proprietor, Judd (Neville Brand), a sexually-demented, scythe-wielding psychopath, initially tries to rape her before slaughtering her with a corn rake and feeding her to his pet crocodile that lives in the pond out back.

It’s the Psycho twist taken to the grisliest extreme. We expect Clara—who, if I recall correctly, is not named prior to her death—to be the protagonist by virtue of her early introduction and perceived innocence. Instead, she fends off sexual assault twice in ten minutes and then hideously meets her end at the hands of a monster who will feature as the centering force in Hooper’s surreal horror show.

And make no mistake—Judd is a worthy villain, no matter what you think of Brand’s theatrical portrayal. Like the Sawyers, Judd is a simple creature, but unstable and thus dangerous. The film’s humor is pitch black and most of it comes from witnessing Judd bumble through his grotesque butchery, enlivened by Brand’s wild mannerisms, lumbering gait, and ferocious bellows. He’s evidently creepy from the get-go; there’s no cheery Norman Bates façade to his personality. He keeps a malnourished pet monkey on his porch and a mannequin in his bedroom for company—you get the picture. At certain points, even after he’s claimed a few victims, he just acts like a mildly kooky guy. He straightens up around the hotel, welcomes new guests, croons to himself, flips through magazines. At others, his vile impulses overtake him and he cannot control himself. But even then—for instance, when he lodges his scythe in the throat of Clara’s father (Mel Ferrer), who’s come looking for his estranged daughter—he acts like a child who’s glimpsed something that his parents hadn’t wanted him to see, simultaneously jittering with delight and scared out of his wits. He’s a madman without a plan, and his unpredictable nature makes him a fascinating focal point.

Shortly after the fake out with Clara, Hooper pulls a different but similarly effective trick when a small family arrives at the Starlight. The viewer mistakenly begins to sense an opportunity to identify with the “normal” characters of Roy (William Finley) and Faye (Marilyn Burns). But no sooner has the crocodile swallowed the family’s pooch than Roy reveals himself to be just as unhinged as Judd. He flounders around on the carpet looking for the eyeball Faye has apparently gouged out, then barks like a dog to torment his daughter, Angie (Kyle Richards). Soon, Roy meets the crocodile when he tries to avenge his puppy dog’s death by shooting it with a shotgun. With Roy out of the picture, in short order Judd has Faye bound and gagged in her bed and Angie trapped under the porch. More guests arrive and the cycle continues until it reaches a fever pitch when Clara’s sister (Crystin Sinclaire), heretofore oblivious to it all, suddenly becomes aware of the woman struggling against her restraints the next room over and hears the cries of the little girl evading both Judd’s scythe and the crocodile outside.

Where The Texas Chainsaw Massacre succeeded by creating a semblance of reality, Eaten Alive does so by completely detaching from it. At no point does Hooper’s set feel like a real place. Despite the passage of time, it’s perpetually dusk at the Starlight Hotel; an otherworldly twilight marked by a dull red glow and lingering plumes of fog. Indeed, the red light is so pervasive that long stretches of the film could easily have been shot in black and white and then tinted red. It’s like watching an Argento picture only the evil witches are replaced by a sadistic redneck man-child with a pet crocodile.

Seemingly diegetic country music blares from unseen radios and contributes to the cacophony of sound alongside the twisted experimental music provided by Hooper and Wayne Bell. Constrained more or less to a single location—there are short forays to the whorehouse and a local bar, which, by contrast, underscore the surreal artificiality of the hotel—Hooper’s main set is gradually stained with blood and the soundtrack increasingly permeated with Faye’s muffled screams and Angie’s high-pitched squeals. Instead of building toward a narrative climax, then, Hooper builds toward a tonal freak-out.

Couching its grotesquery in a lighthearted context and rendering it farcical with gleefully odd performances, Eaten Alive is not trying to provoke with sensuous attacks like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and other contemporary films but to create a nightmarish atmosphere of sleazy amusement. The cartoonish quality that emerges understandably put off many early viewers, but looking back, if it’s not a resounding success, it at least appears ahead of its time, predating the trend of self-aware horror comedies by quite a few years.