“You lack the qualifications to exercise free will.”

I think I get it now. I won’t renege my critique of Metal Gear Solid (because I think it’s largely correct) but playing through its sequel has helped me understand the aims of Hideo Kojima’s postmodern digital age satire. Indeed, he’s done a much better job of it this second (or fourth?) time around. Now, let’s not get carried away here. Sons of Liberty is still lackluster as a gaming experience, even if it’s a cut above the original. The entirety of the main campaign consists of a prologue and one single, albeit bloated, mission. The mechanics and camera are clunky. The enemies are only slightly smarter than Lloyd Christmas and Harry Dunne. You’re still only controlling the action about 20% of the time. The frame story is a grotesque exaggeration of the original’s barely tethered narrative, a hodgepodge of action movie clichés thrown together in a surreal blur. And yet, placed within its proper cultural context and considered as a postmodern storytelling enterprise that transcends and deconstructs its medium, it is quite a daring work, though in my estimation the product as a whole is undeserving of the “genius” label that many try to slap on anything Kojima has touched.

Let’s set aside my disappointment with MGS1 for the moment and consider its cultural impact and reputation. Even before its release the demo had been played by more than ten million people. Many of those who played it purchased the full title—a playable action movie with a veneer of futuristic real-world politics. It raked in the accolades, spawned spinoff material in other mediums, and seemed poised for franchising. Moving from the Playstation to the next generation of consoles upped the ante and fans’ anticipation grew when the trailer for the new game hit the airwaves depicting Solid Snake gunning through the prologue and dueling with a jet. The subsequent demo led the player through a sneak-heavy portion of the initial mission and all signs pointed to a bigger, badder, better-looking version of the original. Players looked forward to guiding the rugged hero of the first game through his new campaign, seeking out and destroying the mobile nuclear weapon, navigating political conspiracies, fighting genetically modified supervillains and myriad faceless terrorists, hiding in cardboard boxes and sneaking beneath the noses of witless guards. But these expectations were deliciously subverted at almost every turn.

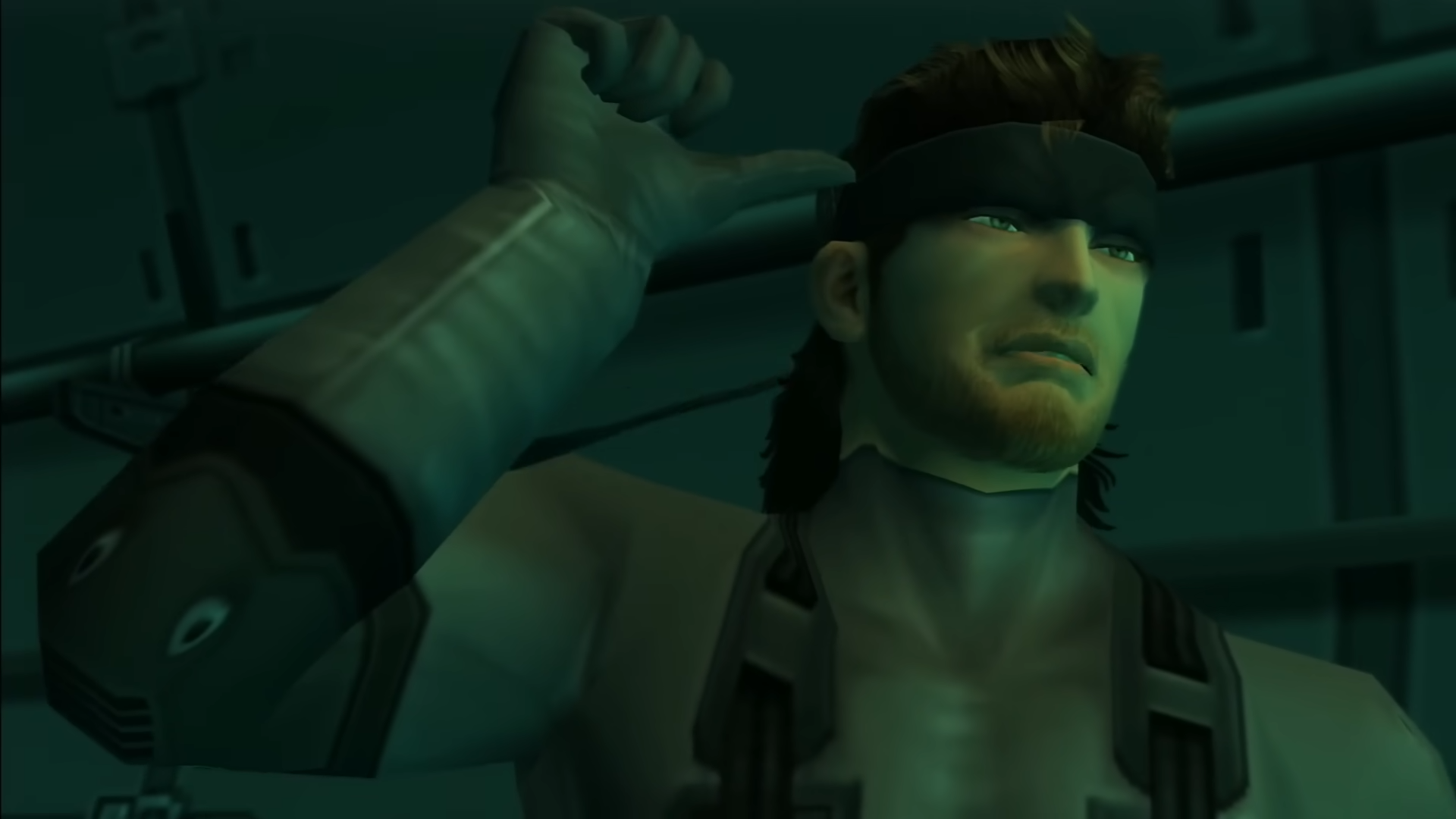

From the get-go, Metal Gear Solid 2 defies what the player was conditioned to expect. The engaging prologue fails to reward the player by ostensibly killing off Solid Snake in an anticlimax. Not only is Snake left for dead, but a new game mechanic is exploited to trap the player into framing him as a terrorist before abandoning him on a scuttled oil tanker without any chance for the player to redeem him. The main mission proceeds to play like a twisted parody of the original game as you take control of newcomer Raiden and infiltrate Big Shell. In the first game, Kojima often messed with the player by withholding narrative rewards after gameplay success. He always balanced this with more or less adequate payoff in due time, but that doesn’t happen here.

Stay away from good-looking women when you’re fighting. Otherwise you’ll get hit with diarrhea.

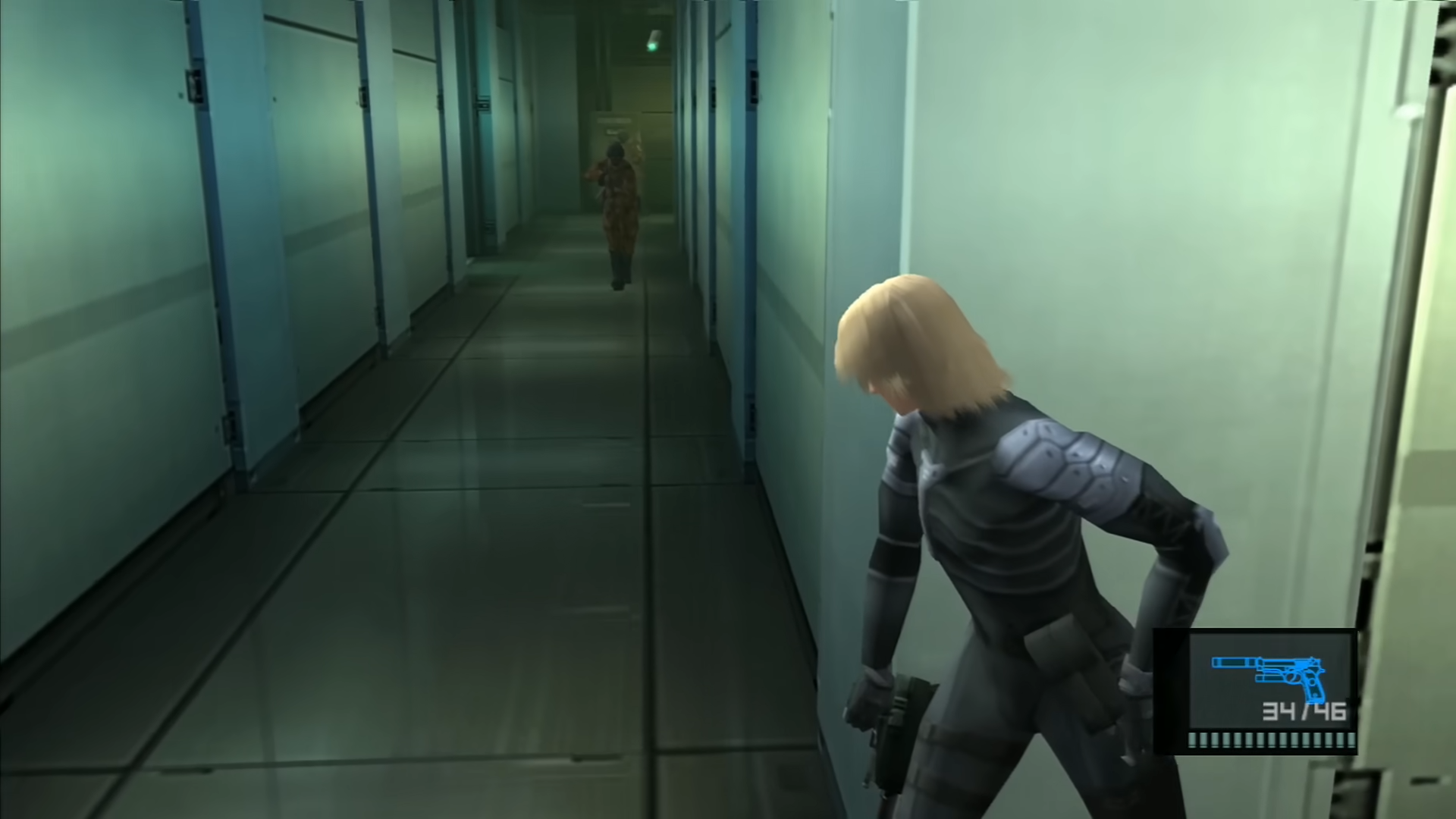

And that’s only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to Kojima toying with player expectations. Take Raiden himself—an effeminate, lithe, uncertain rookie who is the polar opposite of everything that defines Solid Snake. Their differences are evident in their interactions with the support team. In the first game, Snake was in constant communication with a group of experts and allies, several of whom were flirtatious women with whom he was at ease. He also developed a strong camaraderie with Otacon which carried over into the prologue of the second game. In contrast, Raiden begins his mission with only the Colonel and, inexplicably, his girlfriend Rose as support. Both treat Raiden like an idiot, presumably because he is one. He is so timid and emotionally stunted that it becomes unpleasant to wade through the unending codec conversations that take up so much of the game. His goals, too, serve to strip him of his grandiose visions. The bulk of the mission consists of trekking around the plant defusing bombs. One of the boss battles consists of merely surviving via dodge for a few minutes. Snake, who it turns out did not die and is working under the alias Iroquois Pliskin (wasn’t really expecting a Big Trouble in Little China reference), infiltrates Big Shell moments before Raiden and remains a few steps ahead of him, his presence as a non-playable character taunting the player.

Not only is the character of Snake stolen from the player, but the familiar texture of the game is hideously modified as well. In the prologue, as in the original, deaths were followed by a fade to black, an abruptly cutoff electronic hum, and Otacon emitting his famous soundbyte: “Snaaaake!” It was reaffirming the familiar pattern from the first game, promising a similar experience ahead. But when you die while playing as Raiden, the screen goes white. A chintzy synth line bloops out of your television. What’s going on? Kojima is purposefully making the player squirm, that’s what’s going on. Echoes of the first game (even the older MSX/NES games!) are twisted into a self-referential kitsch, the proximity of the older game’s hero and aesthetics clarifying that these shenanigans are intentional. The formal subversion of MGS2 is discussed at length in James Howell’s essay “Driving Off the Map” and Super Bunnyhop’s video essay “Critical Close-up: Metal Gear Solid 2”.

In MGS1, the player was tasked with doing some silly things, like plugging their controller into the second player slot and reading a number off of the game’s physical case. Thankfully that nonsense is absent here. Instead, Kojima uses elements within the game to draw attention to the medium. Video games call for the player to invest themselves in a way that watching movies and reading books do not, the element of control forging a link between player and avatar. Initially, this is lightly hinted at through dialogue but eventually it is revealed that Raiden had trained in a virtual reality simulator—in fact, that he had played MGS1. Further, echoing the first game, it is revealed that the current mission was entirely staged to form Raiden into a battle-hardened warrior on par with Snake. When all players wanted was a few hours of escapism playing as the iconically cool Snake, Kojima responded with a game that told them playing video games would never make them as cool as their digital heroes. Not only that, but by revealing Raiden’s history as a child soldier in the Liberian Civil War—as the player-character lies naked and strapped to a torture rack—he makes playing as a military cog an emphatically uncool thing to do.

I’ve completed three hundred missions in VR. I feel like some kind of legendary mercenary…

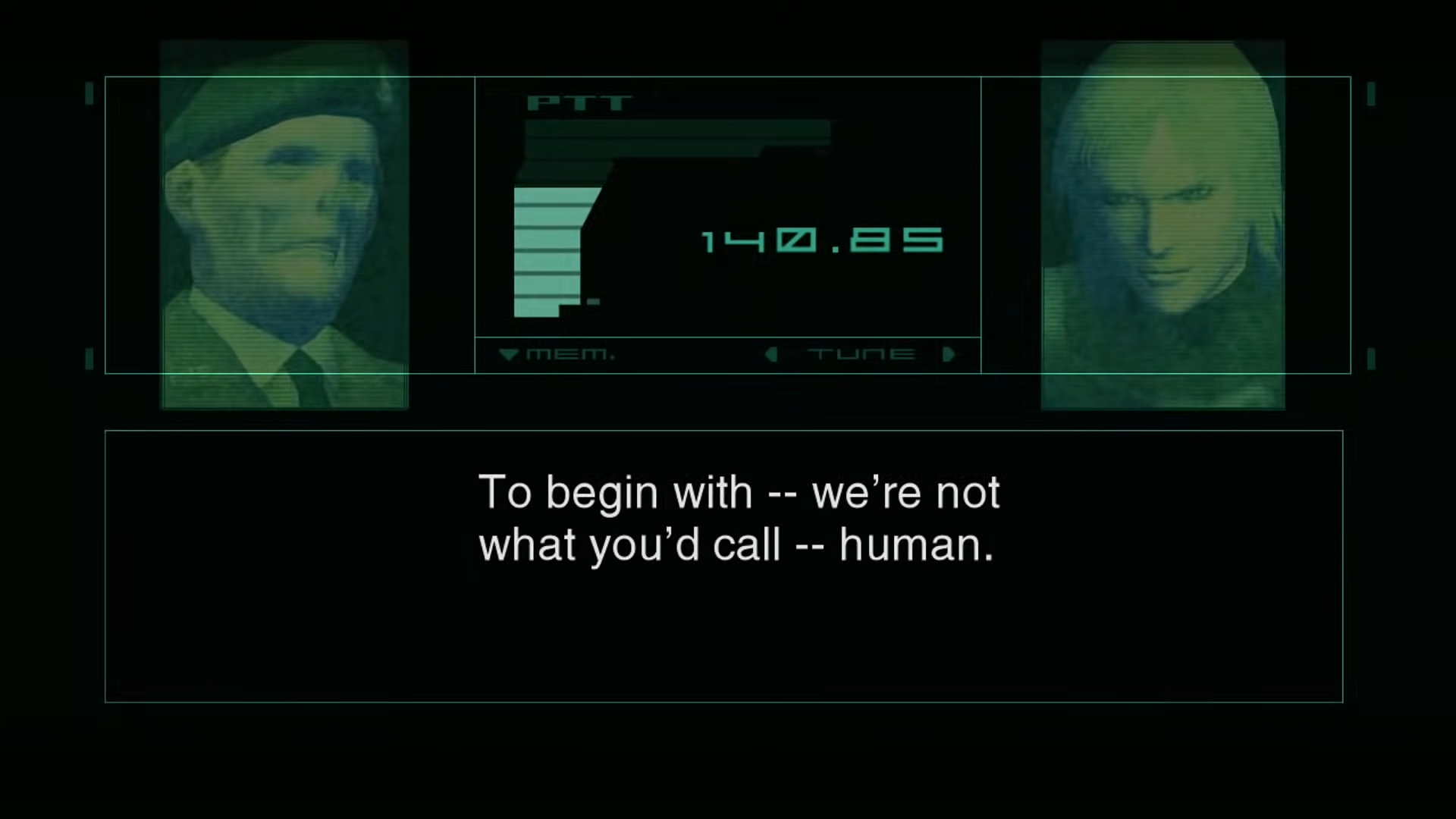

And then we arrive at the plot twist that has been called “the most profound moment in gaming” (watch part two). Not only is the Colonel an AI generated facade, but he is disembodied, spread across the digital landscape and essentially immortal. He—it—explains its aim of wresting control of humanity from humans themselves (if it was in our control to begin with) and steering evolution in the “right” direction. Questions of artificial intelligence, free will, perception of self, genetic mapping, the verity of history, legacy, cyber warfare, digital excess, and information control come into play, and it is revealed that the whole mission has been a fabrication. This points a finger at mankind’s difficulties with parsing truth, exacerbated by the explosion of accessible data in the digital age. It almost seems to suggest that you shouldn’t be playing the game at all and its illustration of behavioral control seems eerily prescient now that social media trends can set talking points for large swaths of the population.

You exercise your right to freedom and this is the result. All rhetoric to avoid conflict and protect each other from hurt. The untested truths spun by different interests continue to churn and accumulate in the sandbox of political correctness and value systems. Everyone withdraws into their own small gated community afraid of a larger forum. They stay inside their little ponds leaking whatever truth suits them into the growing cesspool of society at large. The different cardinal truths neither clash nor mesh. No one is invalidated but no one is right.

As thrilling and thought-provoking as this conversation is in a vacuum, it unfortunately doesn’t actually exist in a vacuum. At this point in the narrative, you’ve already witnessed a supernatural transplanted arm take over the body of its new owner, defeated an obese madman on rollerblades drinking martinis, had a bladderful of urine drained onto your head, and cartwheeled nude through a stage called “Arsenal Jejunum.” The double crosses and conspiracy theories are all over the place but somehow never produce anything surprising. According to Kojima’s design document, this constant blur of narrative action was intentional. But the juxtaposition between the campy story and the heady screed dampens the impact of the philosophically minded conversation considerably.

There’s not much to write home about regarding the actual game elements. A few kinks have been ironed out, a few new abilities added, but you still work your way through with a clunky combination of first and third-person views and locked camera angles. At least you can shoot from the first person view now. Even though combat is still mediocre, the emphasis is on sneaking. There are moments of enjoyment to be found amidst the dross in which you tranquilize guards, evade swiveling security cameras, and hide beneath a cardboard box. But actually playing the game is frustratingly sidelined again. On my second playthrough on Extreme difficulty I think I spent more time waiting for cutscenes to load and skipping them than I did controlling Raiden. At least I cannot accuse it of being a subpar animated movie like the last time, considering how vital its gameness is to its storytelling.

By jumbling the familiar form of MGS1 Kojima created a frustrating narrative experience that is not quite justified by its late moments of clairvoyant social commentary. Such thought-provoking narrative turns would have been better served by a more grounded narrative rather than the supernatural military sci-fi soap opera that Kojima dreamed up.