“I’m like the only girl with a decapitated head for a boyfriend.”

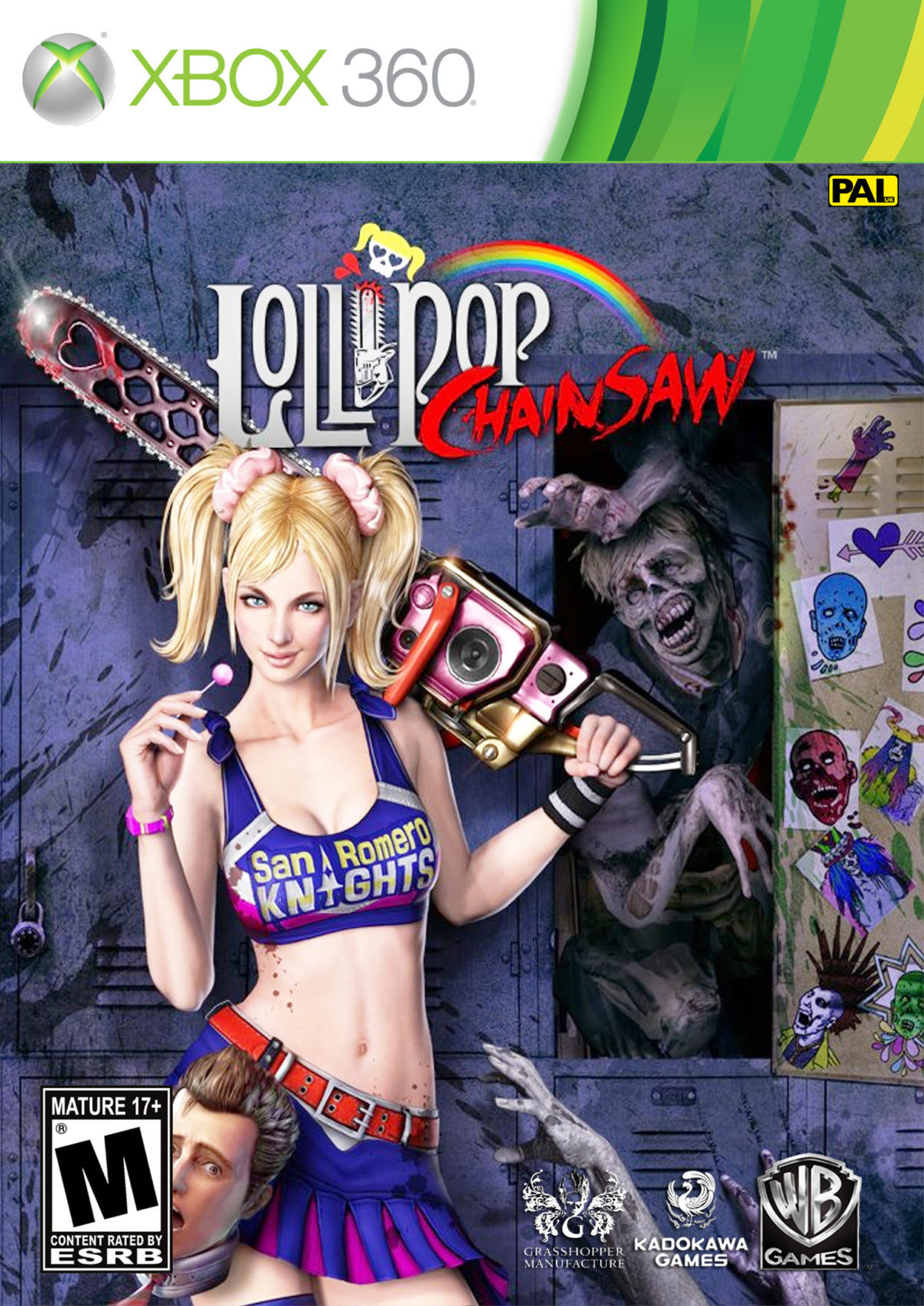

Few games are as boldly committed to ludicrousness as Lollipop Chainsaw. Featuring an overtly sexualized zombie hunting high school cheerleader wielding an oversized chainsaw and pompoms as its protagonist, it recalls the assault of cheap fun that the best of the quarter-eating arcade games of yesteryear had to offer. From the scantily clad hero to the inane dialogue to the outrageous bosses to the tropey level themes to the stupendously varied soundtrack, it is unashamedly dedicated to the best kind of camp. A collaboration between Suda51 (Shadows of the Damned) and filmmaker James Gunn (Guardians of the Galaxy), Lollipop Chainsaw sets its bizarre tone from the getgo and never lets up through six levels’ worth of zombie-slaying extravaganza. Its self-assured presentation allows for an overload of zany contrivances to blend right into the goofy mixture as we move from psychedelic farms to death metal concerts to UFOs, from using zombie heads as basketballs to mowing over them by the hundreds in a combine, all culminating in a final boss battle that takes the player into the viscera of a giant solidified amalgam of a legion of undead called Killabilly.

You play as Juliet Starling, a freshly minted adult who is as airheaded as they come. She’s also a paragon of physical prowess, able to backflip and swing a chainsaw simultaneously for hours on end. She’s one of three sisters born to a family with a history of zombie hunting. Under the tutelage of the wrinkled old Sensei Morikawa—with whom she may or may not have an illicit sexual relationship—she’s become a ruthless slayer of the undead. On her eighteenth birthday, as she rides her bike to meet her boyfriend Nick, she discovers that there’s been a zombie outbreak at San Romero High, prompting her to reach into her duffel bag, whip out her glitzy chainsaw, and start shredding rotted flesh.

She catches up with Nick a second too late. Despite his best efforts, he is unable to fend off the zombie attack and he suffers a bite that will rapidly transform him into one of the feral creatures. To prevent this occurrence, Juliet simply lops off his head and hangs it from her skirt, where he will spend the rest of the game—except for when she shoots him out of a cannon or dropkicks him or sticks his noggin on a headless zombie when she needs some physical assistance. Nick serves as the player/audience surrogate and spews a steady stream of hilarious comments. Indeed, the banter between Nick and Juliet is one of the major highlights of the game, as it eagerly pokes fun at the game’s own excessiveness and leans into a hyperactive, beyond-perverted brand of comedy. While the game is laced with profanity and endless sexual innuendo, there are plenty of genuinely funny bits of dialogue that wring humor out of the absurd premise and increasingly janky storyline. One of my favorites occurs when Nick, just a bodiless spectator swinging from his girlfriend’s waist at this point, expresses incredulity that Juliet trains with a sensei. He tries to verify that by “sensei” she means “teacher” and Juliet extrapolates his question to mean that he is fluent in Japanese and begins flinging sentences at him. Later, when Nick begins to accept Juliet’s secret occupation, he asks her if she has killed anything besides zombies. She starts rattling off other mythical creatures—sasquatches, leprechauns, frankenberries… “Frankenberries! Like the cereal?” Nick asks. “Ugh, that is total propaganda,” Juliet replies. The dialogue is so much fun that when I grew frustrated with a few gameplay elements I found myself wishing they had just made the story into a short-run anime.

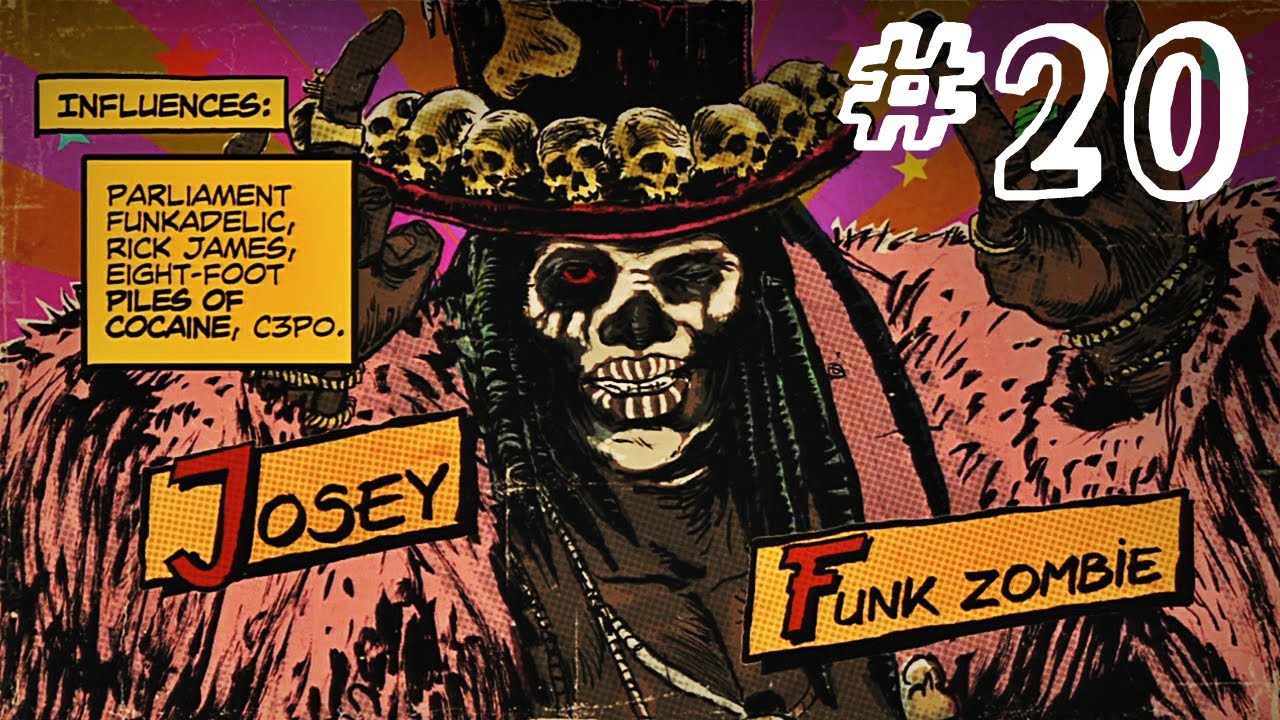

At no point does Lollipop Chainsaw take itself seriously. It begins with Juliet welcoming the player to her bedroom while doing a split atop her mattress, overtly sexualized. The undead legions consist of buskers, firemen, cops, football players, grannies, farmers, hillbillies, robots, the list goes on. They speak nonsensical nastiness about poop and pee and blood before Juliet delimbs and decapitates them, and their overlords—the game’s bosses—consist of viking warriors, punk rockers, demon-possessed hippies, leather-clad bikers, and P-funk voodoo shamans. This kitschy brutality is emphasized further by the inspired, eclectic soundtrack, which features such diverse acts as the Chordettes (the requisite “Lollipop”), Joan Jett and the Black Hearts, Buckner & Garcia, The Toy Dolls, Five Finger Death Punch, Dragonforce, Skrillex, and Sleigh Bells, as well as original music by musician Jimmy Urine (who also voices one of the bosses). The closest comparison I can think of in terms of its outrageous absurd comedic tone is FLCL.

Slain zombies drop loot which is used to purchase passive health and strength upgrades as well as nifty new combos that make Juliet’s gymnastic ability even more unbelievable—think triple front flipping while holding the chainsaw extended for max carnage. Although the combos are mostly simple sequences of button presses, there is a good bit of variety and the animations are suitably over-the-top. As zombies lose limbs, they’ll attack Juliet differently, so varied attacks and dodges may prove useful. As more combos unlock and Juliet’s abilities increase, the combat, which starts out slightly clunky, begins to flow pretty smoothly and is much more fun.

Juliet can also use her pompoms to beat zombies into a starry-eyed stupor which allows for automatic decapitation if they catch a swing from the chainsaw blade. If three or more zombies are decapitated at once, Juliet enters into a canned animation that awards the player with extra rewards for “Sparkle Hunting.” There’s also a meter that gradually fills up as you hack away that, once filled, the player can engage for a momentary one-hit-kill ability while Toni Basil’s “Mickey” blasts through the speakers. One can play through the game for the simple joy of the whacky story, twisted aesthetic, and offbeat humor, but as Juliet’s abilities are padded and the zombie-sawing becomes more natural, end-of-level scorecards will encourage running through the levels again, and increased abilities make doing so more fun than the initial playthrough.

While I love so much about Lollipop Chainsaw, it contains several elements that are quite aggravating. The most frustrating thing, which was easily avoidable, is how often the game stops for silly reasons. Dozens of unskippable, slightly funny phone calls from Juliet’s mother, hundreds of mini “cutscenes” where the camera just pans over the next little segment of the course, introducing generic enemies with five-seconds of blandness, countless instances where you have to chainsaw through trees and doors and cars that stand in your way. All of these little interruptions needlessly disrupt the flow of the game. Also annoying were the minigames, which seem to have been included in an effort to add some variety to the gameplay. None of them are especially fun, although most fit within the spirit of the game. Two in particular—zombie baseball and the gondola—are too exasperating to be granted a pass. And the over-reliance on quick-time events does the game no favors. I consider those gripes small, but their presence is pervasive and severely diminished my enjoyment of the game..

But in the final analysis, Lollipop Chainsaw is great fun despite its flaws. The warped humor of the team at Grasshopper Manufacture is on point, and the clash of bright colors, grimy punk aesthetics, and cheery soundtrack make for a novel assault on the senses. It regularly toes the line of good taste, jumping around to different ideas whimsically and wiggling its way under your skin. It’s bound to turn many off, but some will smile giddily as they simultaneously decapitate nine zombies atop a background of rainbows and cheery pop music. Some may see it as a basic game dressed up with gimcrack ornamentation. And to some extent it is. It’s not mechanically polished or brave as far as gameplay goes. But it’s an endearing celebration of an older era when games could be dumb and outrageous fun and everyone agreed that was okay. It is simple and stupid, yes, but there’s plenty of fun to be had if you look past the boobs, glitter, and guts, even if those are its raison d’être.