“It’s easy to forget what a sin is in the middle of a battlefield.”

General consensus would suggest that Metal Gear Solid is the greatest Playstation game of all time. I contend that it is scarcely a game at all. The core stealth mechanics provide some limited fun, for sure, but you spend so little time actually utilizing them that the gameplay was almost entirely absent from my impression of the game shortly after playing it. Instead, what lingers are the absurdly long cutscenes, the endless “codec” conversations, the moral posturing, and the gaping plotholes. Retrospective reviewers gaze pompously through their rose-tinted glasses, struggling to keep straight faces as they air their plentiful grievances while maintaining the game’s greatness. They use phrases like “it’s a beautiful mess” or “we can’t quite pin down why it’s good despite its many cardinal sins.” Their ultimate justification for lauding the game is basically that it is a classic—an endorsement that rings hollow.

To be clear, the enjoyment of objectively bad things is perfectly legitimate—hence the appeal of trash cinema, the success of Hallmark movies, most popular music, pulp fiction novels—but these strangely alluring titles are guilty pleasures; they don’t belong in the conversation of greatest of all time unless we’re adding qualifiers to that designation. If you encounter someone who earnestly believes that, say, The Rock, is the pinnacle of cinematic achievement then you know you are speaking to someone without taste.

I think people generally understand this concept, so I am confused why Metal Gear Solid is regarded so highly. My hunch is that most people don’t read enough books and only watch blockbuster movies, so they think that the thematically scatterbrained story of MGS—which jumps from anti-war commentary to daddy issues to standard Hollywood clichés to confused sexuality, and is characterized as much by drastic tonal shifts and massive logic gaps as by political, social, or moral commentary—is saying something profound. It’s emphatically not. What’s actually happening is a confused man with some really cool ideas bouncing around in his head is throwing them all at the wall at once and begging for the result to be taken seriously as a work of art.

It is not an exaggeration to say that for every minute you spend controlling Solid Snake, you spend two or three minutes with your controller in your lap. When you are actually playing the game, it’s fun, but fairly simple. You sneak around the level in top down view, avoiding the limited range of the guards’ patrol. The generic enemies are all “genome soldiers”—cloned from the same ‘Big Boss’ stock as Snake himself—and apparently have enhanced senses, but they’re actually pretty dumb. You can lure them out of their routine by placing nudie mags in their path; you can hide beneath a cardboard box in plain sight; and, if spotted, you need only evade them for a few seconds before they forget about you entirely. These stealth sections were ostensibly the selling point of the game (the tagline is “Tactical Espionage Action”), and indeed, they’re basically the only element that resembles what I would call a game at all.

While the game utilizes many of the forgivable leaps of “video game logic” that are common—e.g. eating a granola bar instantly heals gunshot wounds—it also is plagued by a postmodern pretentiousness. For instance, the only way to beat one of the bosses is to unplug your controller and move it from the first slot to the second slot to prevent Psycho Mantis from reading your mind. You’re also told by your commander to look at your CD case for a radio frequency; not a CD case in Snake’s inventory, but the actual case that the game came in. But if that’s all the game was, it would still be a decently fun one, along the lines of a solid old school Nintendo game. But the problem is you only spend about a quarter of your time actually playing it.

Instead of belaboring the dearth of actual game to play, I’ll take this thing on its own terms. The series’ many fans tout Hideo Kojima’s complex narrative, conspiratorial themes, and cinematic presentation as the game’s strong points. The story in MGS is so contrived and tonally inconsistent as to mitigate all dramatic tension and player/viewer investment. The writer wants to have his characters wax philosophical about the futility and injustice of war and nuclear armament, but also melodramatically flirt amidst a high-stakes espionage mission. He presents Snake as a hardened, no-nonsense soldier, but he also has idle time mid-infiltration to fall in love and to talk about jiggly buttcheeks. Kojima wants us to take his geopolitical musings seriously, and for the drawn out deathbed speeches to have dramatic impact. But we also must accept that Liquid Snake—Solid Snake’s long lost homosexual British clone-twin with a blonde mullet—was actually pulling all the strings behind the scenes, a fact which essentially retcons a large portion of the plot before the game is even over. We also have to agree that in a world where nuclear-armed tanks and nuclear-armed submarines exist, a nuclear-armed vehicle with legs—the horror, the horror!—is the be-all end-all of terrorist weaponry, forcing Snake out of retirement for a solo mission to Shadow Moses Island. Once the whole we-were-tricking-you-the-whole-time element comes to light, Snake is informed that he was brought to the military compound—complete with tax-funded trap doors—because he carries a virus that only kills specific people as soon as they are exposed to it. Well, they only die immediately if Kojima can’t come up with some contrived speech for them to recite just before they keel over from cardiac arrest.

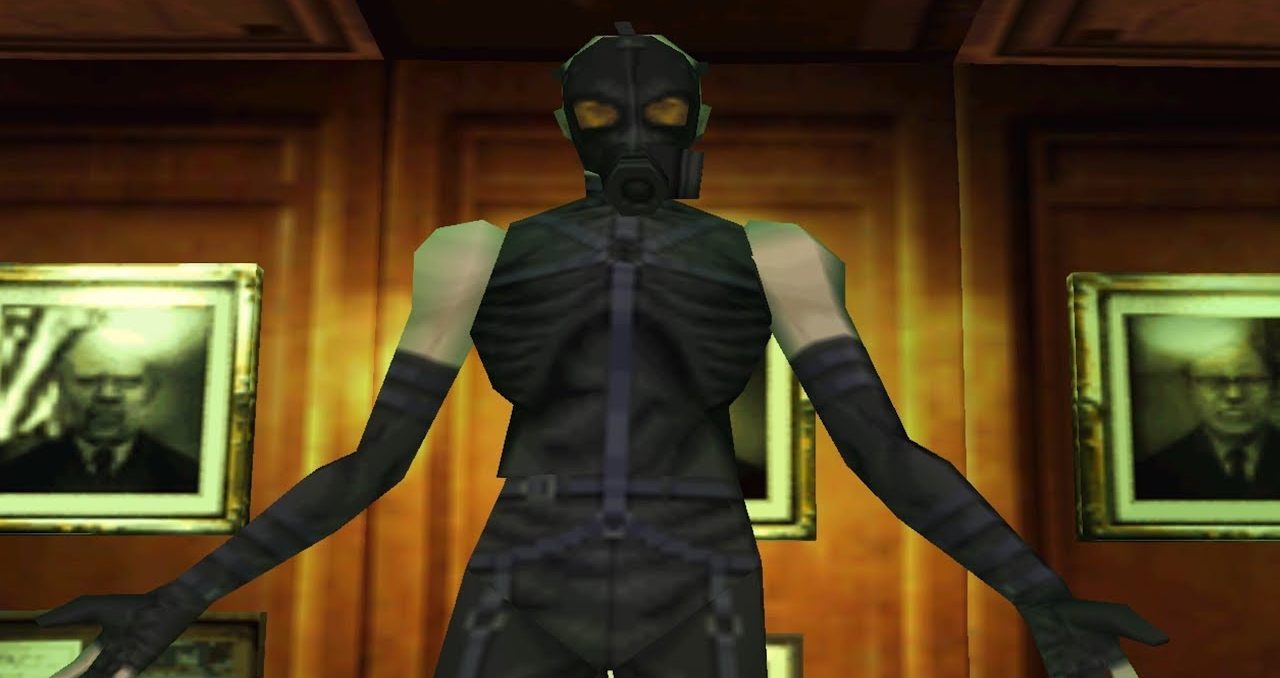

I’m not decrying any of these elements as inherently bad—hammy and ham-handed, definitely, but not necessarily unusable. The issue is that they’re assembled with such a taint of bathos that it’s not worth the emotional investment from the “player.” The outrageous plot is suited for a fun anime series, but its constant moralizing and self-seriousness prevent any delight that might be gleaned from its campy performances. I can get behind oversized Gatling guns, homoerotic cyborg ninjas, and Snake disobeying orders by smuggling a pack of cigarettes with him “in his stomach” (meaning he retrieved them via puke or poop). I can even stomach the fact that the terrorists were basically bluffing the whole time and that their plot would have failed if Snake had actually been killed during his mission (meaning all those guards shooting at you and all those boss fights were all staged?). That’s all cheesy stuff that can work in the right context. But that creates a complete tonal mismatch when paired with footage of Hiroshima, which plays as Otacon informs us that his grandfather had worked on the Manhattan Project and his father was born on the day of the bombing of Hiroshima. It tries to be profound, ironic, subtle, and moving—and smugly shambles on as if it is—but it’s just a mess (and not a beautiful one).

And I haven’t even really dwelt on the fact that much of this dialogue is presented via “codec” rather than the touted cinematic cutscenes. These “codec” interruptions are just green faces on a black screen going through canned animations while dialogue plays; the “codec” is explained in the game as some kind of multi-frequency radio that’s lodged in Snake’s ear canal but which also allows him to see who he is speaking with. Most of these scenes are skippable, but they’re like, “the meat” of the game, so to speak, so what can you do.

The thing is that movies are just way better at being movies than games are. Taking control away from the player needs to have a purpose; Metal Gear Solid struggles to find a reason to ever give it to them to begin with. The resulting experience is a self-indulgent B-movie presented with way worse animation than an animated film, written by someone who viewed themselves as some kind of renegade mystic who could speak only the truth. It barely qualifies as a game and pales in comparison to the films that it aspires to be categorized alongside.

In general, I find it difficult to approach sacred cows like this one because I inevitably critique them against their reputations. That is to say, Metal Gear Solid probably isn’t the steaming pile of phooey that I made it out to be; but it most definitely does not stack up against the retrospective acclaim it still receives.