“I am having a hallucination now, I don’t need drugs for that.”

I don’t know if I’ll ever really get Thomas Pynchon. He’s just so eccentric and impenetrable that, while I remain transfixed by his style and depth and breadth of detail, I can’t help but feel like he’s either still several levels over my head or that his writing has no meaning at all beyond it’s lingual and metatextual showboating. Almost all of his novels are door stoppers, save The Crying of Lot 49, which is a slim volume dealing with a conspiracy theory regarding rival postal companies. The first time I read it, I did so in a single sitting and remember thinking it was one of the most bizarre but entrancing things I had encountered. Then I tried to wade through the murky mindbend of Gravity’s Rainbow and found that this guy’s work requires concentration and large chunks of time. A chapter here and there wouldn’t cut it, because I would lose all the threads of the complex tapestry he was weaving (if he was weaving one at all). I’ve yet to tackle another of his behemoths, but I have read a smattering of other authors who often crop up in discussions in the same breath as Pynchon for one reason or another—Vladimir Nabokov, Don DeLillo, David Foster Wallace. So I wanted to try Lot 49 again to see if my sensibilities have changed or if I could understand it better.

Little has changed, at least as far as Pynchon goes. I’m still captivated by his masterful command of language and his methodical building of paranoiac tension. And I’m still mostly lost as I try to parse out any real meaning from the book. Approaching complex texts with the intention of understanding them—to break them down into a their constituent parts and point to the elemental building blocks—has proven to be a nearly futile task for me. I think part of it is that I don’t really want to understand it from a mathematical standpoint. There needs to be something more than a formula behind writing a compelling novel, and to try to graft one onto something that seems inspired doesn’t feel right.

Another part of the solution to this predicament is to realize that books like this one are not necessarily about their ostensible subjects. It seems to me that Pynchon isn’t really writing about the topical matters with which the novel’s protagonist, Oedipa Maas, is concerned. The rival postal companies, the gay bars, the censored revenge play, the mysterious symbols, the psychotherapist who loses his mind, the monologue about LSD—these are all incidental elements that serve Pynchon’s larger purpose of subtly instigating unease and a sense of paranoia in the reader. He achieves this by giving us incredible detail, often to the point of extreme frivolity, in areas where we wouldn’t expect it, and leaving other things—things that are usually important—inadequately explained.

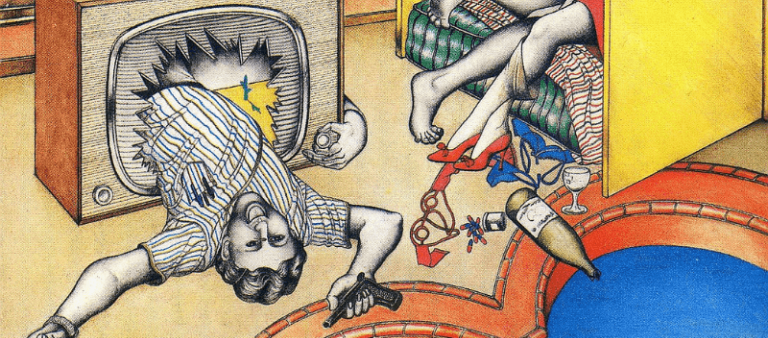

The novel begins with Oedipa learning that she was named executrix of her late lover’s estate. Pierce Inverarity had been a massively successful real estate mogul, and when Oedipa leaves her disc jockey husband and LSD-pushing therapist behind to perform her function as executrix, she discovers that the man seems to have owned or financed nearly every establishment in San Narciso. The first evening she spends in the city, during which she shacks up with the dead mogul’s lawyer, sets the offbeat tone for the rest of the novel. It turns out that Metzger, the lawyer, is a former child actor, and one of his old movies is on the television. He uses her doubt of the coincidence to lure her into a game of strip film trivia while a group of teenage rockstar-wannabes throw a concert outside the motel and voyeuristically peep in on the pair. Oedipa is uncertain of the situation… maybe the whole thing was a setup and Pierce isn’t really dead at all.

Such a captive maiden, having plenty of time to think, soon realizes that her tower, its height and architecture, are like her ego only incidental: that what really keeps her where she is is magic, anonymous and malignant, visited on her from outside and for no reason at all. Having no apparatus except gut fear and female cunning to examine this formless magic, to understand how it works, how to measure its field strength, count its lines of force, she may fall back on superstition, or take up a useful hobby like embroidery, or go mad, or marry a disk jockey. If the tower is everywhere and the knight of deliverance no proof against its magic, what else?

But then things get weirder, and answers become less likely to materialize the deeper she searches. She begins to encounter the mysterious W.A.S.T.E. symbol. She learns that Inverarity was involved with the mafia and had once tried to sell human bones on the black market. A vague mental connection of events from a member of The Paranoids (the teenage rock band) leads to Oedipa purchasing a ticket to a revenge play called The Courier’s Tragedy, which hints at a deeper conspiracy further evidenced by mysterious watermarks on Inverarity’s vast stamp collection. She suspects, based on her very limited and clearly insufficient data, that a renegade postal service is operating as some kind of secret underground society.

She tries to confirm her suspicions by following a courier who places a parcel into a literal trash can (not so curiously marked with the word “WASTE”); she interrogates the play’s director to no avail, and then traces down an older copy of the script; she bluffs her way into using some kind of psychic machine that proves similarly fruitless. The symbol, that of a muted horn, begins appearing everywhere she looks—children’s chalk drawings on the sidewalk, technical schematics, mindless doodles, shop window displays. The book ends without resolution—Oedipa is stuck in a semi-permanent state of hypertension, uncertain whether the mystery of Trystero is an extended hallucinatory episode in which her subconscious incorrectly stitched together these disparate bits of info, or if it is a real underground society, or if her late lover decided to stage an elaborate hoax.

She looked down a slope, needing to squint for the sunlight, onto a vast sprawl of houses which had grown up all together, like a well-tended crop, from the dull brown earth; and she thought of the time she’d opened a transistor radio to replace a battery and seen her first printed circuit. The ordered swirl of houses and streets, from this high angle, sprang at her now with the same unexpected, astonishing clarity as the circuit card had. Though she knew even less about radios than about Southern Californians, there were to both outward patterns a hieroglyphic sense of concealed meaning, of an intent to communicate.

Like the uncertainty of the book’s protagonist, this reader is likewise uncertain what to make of the book itself. It was inventive, funny, layered, verbose… but what does it actually say? Does it matter that the characters don’t act or talk like real people, or even like standard literary characters with the medium’s accepted contrivances? Is it okay that I’m not sure why Pynchon named his book’s resident stamp expert Genghis Cohen, other than to make people nod and think, “Oh, like Genghis Khan, the Mongol Emperor who killed all those people”? Do any of the references within its pages mean anything, or is each one just a superficial red herring? Does it matter if it’s almost completely style, written entirely to build a mood?

In a standard novel, the reader gathers enough info through the characters such that the conclusion is logical and coherent. In The Crying of Lot 49, the protagonist herself is routinely sideswiped by new information, such that she is still searching for a crucial breadcrumb to resolve the mystery when the book abruptly ends. Throughout the book, she proposes her brewing theory to a slew of interesting minor characters, each of whom posit mutually incompatible theories of their own. This leads the reader to scratch their head and wonder what exactly they’ve just read. The main takeaway can’t be about Oedipa Maas’s adventure, because even she is unsure what exactly occurred—in fact, it’s entirely possible that nothing occurred. If we zoom out, we’re left with a book that is chock full of interesting words, complex sentence structures, and esoteric references, but ultimately is about engendering an anxious state of mind through flavorful prose and misdirection. That is to say, it’s basically hollow, but its shell is delectable if you have a taste for the sort of postmodern shenanigans that Pynchon engages in.