“This place can’t be real. It’s like jumbled up memories.”

My most cherished memory of The Evil Within has almost nothing to do with the game itself—which is fine with me because overall it was quite an underwhelming experience. At one point during my second playthrough, I was spinning my tires on a particularly annoying boss fight. This second playthrough was done on “AKUMU” difficulty where the player dies if they take any damage at all. Couple this fact with the game’s frequently clunky mechanics and the long load times after dying, and I found myself with small moments of idleness during which I could scour the internet for the thoughts of others who were as frustrated as I was at this game’s cheap tactics.

I was stuck on a section about ⅔ of the way through the game, where you have to confront Laura, a six-limbed horror that looks like a mutated version of the girl from Ringu. On Survival/Medium difficulty, I persisted until I defeated Laura; but on AKUMU, I elected to evade and escape. Even this was an annoying challenge to overcome. I tried it countless times, honing my route and committing the intricate movements to muscle memory. Reload checkpoint; sprint around corner; crouch, disarm bear trap; maneuver camera during disarm animation; stand up, aim revolver at bomb on wall; wait split second for Laura to be near bomb, then shoot it; swing camera to first lever on far wall, shoot it; back up, but not too far; allow Laura to get close enough to swipe, but leave enough room behind you that you can evade by backing up; shoot lever overhead; sprint to the left and hope Laura hasn’t recovered from first swipe; 150° turn; aim low and use forward motion to move aiming reticle up onto third lever (must perform on the run or Laura will catch you); turn right and run even if flames have not yet disappeared, rather die by fire than let Laura get you; and on and on.

The whole section takes about two minutes once you get it right, but it took me a couple hours of real time to power through. In its repetition, it emphasized much of what I found frustrating about the game as a whole. For instance, a non-zero percentage of my run’s were derailed because I was seemingly using rubber bullets—I’d shoot a valve, I’d be visually rewarded with a puff of dust on the lever, and yet it would remain unmoved. There wasn’t time for a second shot, so I’d take one on the chin from Laura. Sixty seconds of loading screen, try again. In such a confined battleground, the camera and fine character movement become ultra-important, and neither are great. I don’t feel like trying to describe in words how clunky these issues make the game, but suffice to say there were far too many deaths, even in just this section of the game, where my rapid button presses went as smoothly as I could have hoped—no silly mental hiccups—and yet Sebastian would manage to stray outside of my expected movement scheme, sticking his arm into a gushing flame (dead), sticking his heel into a bear trap (dead), whiffing on tossing a match onto a combustible corpse and so surrendering himself to the clutches of Laura (dead). And again, there were times when I shot at things, including enemies, where it was clear I hit my target and yet there was no effect.

Anyway, after dozens of rounds of this with still no success, I found myself on a forum where someone was venting about this boss fight. After a handful of posts of encouragement, one of the posters posited that, if one could make it through Chapter 10, there was a lot to like in Chapter 11. This poster liked Chapter 11 because it was visually creative—you fight your way through a crumbling city where buildings move and rearrange themselves. This distinctive visual image was clearly inspired by Dark City, a lesser known favorite of mine with similar themes to The Matrix (Dark City came first!). And so during my momentary respite from the frantic boss fight with Laura, I spent a few minutes pleasantly reading through a series of posts that introduced some gamers to a handful of delightful movies. First, Dark City, then The 13th Floor, They Live, World on a Wire. Someone even mentioned Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation and launched into a discussion of false memories.

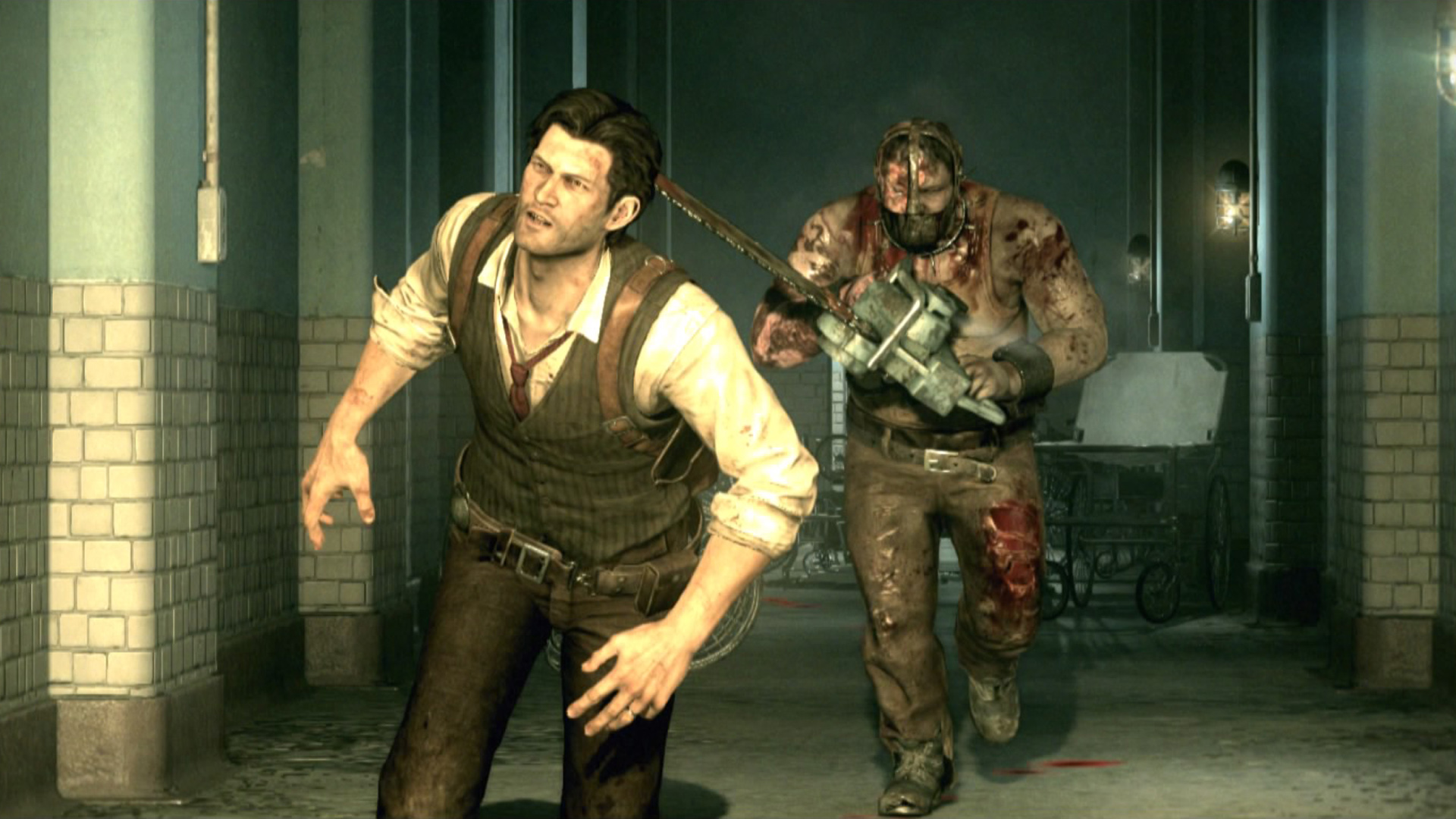

Those heavy-hitting works point toward the lofty aims of The Evil Within, but unfortunately, its story never coalesces into anything worthwhile. Basically, the writers tipped things off the rails by relying on a succession of grotesque tropes as a substitute for coherent storytelling. Rather than building tension, developing the game’s world, or whatever you like your games to do, storywise, The Evil Within is just a series of meandering scenes that try to one-up the previous ones in shock value. While there are cool individual elements, they’re haphazardly thrown at you without any narrative justification; and so while you’re bound to remember some of the distinctive visual aesthetic (which is splendidly grisly and the best part of the game, if you’re into that kind of thing), the actual details of the story are soft and meaningless. It arrives at its conclusion limping like its protagonist does in the first chapter when his leg is sliced by a brute with a chainsaw. (I am aware that some crucial story elements are contained in a series of DLCs; but since the main game was not that compelling, I don’t think that I’ll reward the developers for keeping those details out of the vanilla game.)

But story isn’t everything, and I like plenty of games without one (e.g. Doom). What matters is good gameplay. We’re playing a game after all. The most irksome thing about The Evil Within and its sloppy mechanics is that it could have been great with a bit of fine tuning and better level design. I think that Chapter 3, in particular, highlights where the game should have gone. In this level, you must clear out a small village consisting of several houses, a barn, and a watchtower. It’s littered with traps and zombies, and a sniper on a balcony. To finish the level, you must take on The Sadist, a chainsaw-wielding hulk who soaks up several clips of ammunition. It is a very nice blend of stealth and horror, with a minimal amount of the trial-and-error that mars some of the later sections of the game. You can go in guns blazing, or, with some forethought, you can clear most of the level without any enemies detecting your presence at all. I preferred the latter method, which saves ammo but takes more time. Because much of the challenge of being stealthy lies in maneuvering in the shadows and timing your hidden approaches for knife kills from behind, the unpolished controls don’t hinder the flow of the game very much at this point. It was pulse-raising, but very satisfying to complete because of the creative design and solid flow.

Unfortunately, the game quickly moves away from any semblance of stealth. The encounters throughout the game tend to be ambushes, basically, where you have no choice but to face the enemies head on. But the controls and movements simply aren’t refined enough for fast-paced combat. Shooting feels sluggish, meleeing is a last resort gamble that whiffs half the time (for some reason Sebastian doesn’t use his knife unless you’re sneak-killing a zombie with a skull-stab), and dodging enemies seems tied to a probability rather than anything consistent that would allow you to get a “feel” for a safe proximity. You can upgrade your abilities, such as sprint speed and health, your weapon attributes, and ammo-carrying capacity, but these things don’t really affect the game all that much.

There’s also an option (turned on when you start the game) of having letterboxed black bars that shorten the screen, making it an even more tense experience. (You can see the difference in screen heights in the images in this post.) I gave them a chance, but turned them off as soon as I realized the game was becoming combat-centric. Cinematic aspect ratio only works when, you know, scenes are framed cinematically. But when you’re playing a game you’re concerned with playing the game, not with framing the scene cinematically, so what’s the point? It just makes the game more tedious to play. If the intention was to make the game more tedious to play, then, um, it worked, good job?

Ultimately, the problem with The Evil Within is simply its lack of refinement. I would have preferred the stealth game promised by its opening chapters, but I could have been content with the action game it morphed into. But the controls, camera, and gunplay are simply not solid enough to hold up the fast-paced action that constitutes the bulk of the game. Not to go too far into the weeds, but I think it bears mentioning that games that require trial-and-error like this are not inherently bad. Games like Mirror’s Edge and The Club are satisfying specifically because of the way that you must piece together a route bit by bit until you achieve a perfect run. You have to do this in The Evil Within too, but its mechanics are so unpolished that finally completing a tough section brings a feeling of relief rather than elation. You’re happy to never play it again, rather than excited about your achievement.

What could have been a delightful swan song for director Shinji Mikami (Resident Evil 4, Vanquish) is instead of a tedious exercise in frustrating game design. The Evil Within has no idea what it wants to be. Or maybe it wants to be too many things at once. Its scattered gameplay elements are thrown at the player without any discernible structure. Its story is geared exclusively around moments of visual shock, without any real effort toward a legitimate narrative, horrific or otherwise. It’s best attribute, it’s nightmarish visual aesthetic, is one that doesn’t really enthuse me, and would only really matter if the game was good in other areas. It’s a disappointing, blood-soaked affair, and an unfortunate send off to one of gaming history’s greats.