“Now you know the rules and the techniques, it’s time to begin the tournament for real.”

As we’ve traversed further into a technology-dominated and media-saturated culture, the video game industry has splintered in interesting ways. On the one hand, consoles have been fitted with increasingly powerful hardware, resulting in improved graphics, longer campaigns, and more players competing in online game modes. But that increase in capability has also led to severe over-tweaking—adding wrinkles for the sake of adding them, overwhelming the player with meaningless choices and detracting from what should be a pleasant experience. Do things like complex skill trees, limitless dialogue options, hyper-detailed character animations, and customizable character appearances actually add significant value to a game? On the other hand, back-to-basics type games, often beginning their life on mobile platforms or as download-only titles sold for relative pennies on the dollar, have also taken off. Probably the purest and easiest example of this phenomenon is the paragon of indie success known as Minecraft. These types of games are built from initial concepts based around core design rather than peripheral elements like story and graphics, and thus avoid a flashy but bland final product. One can argue that video games are a legitimate storytelling medium; and I agree, I just think that most games fail to match the storytelling prowess of cinema or literature because they neglect to utilize their primary advantage—they are interactive! While this dichotomy isn’t indicative of a game’s overall quality—I like and dislike games from both categories (and my taste is perfectly aligned with the inherent quality of the media I consume)—I tend to favor games that do something that could not be done in another medium. In other words, a game first needs to convince me why I should spend time playing it instead of watching the movie that it’s ripping its style from.

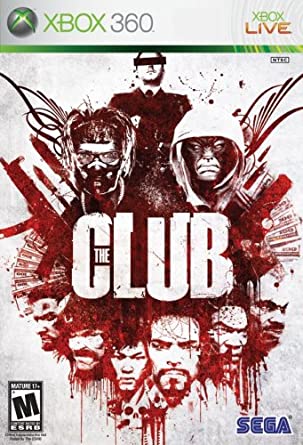

All that long-winded pontification to introduce The Club, a delightfully simple game with only the baldest attempt at storytelling. The concept is simple: combine the constant forward momentum of racing games with the mental and phalangeal dexterity and scoring system of arcade shooters. In the conceptual stages The Club had no story or style at all—it didn’t even have enemies. Instead of doing circuits around abandoned mansions as a contestant in a ruthless bloodsport, the player was moving through shooting galleries and firing at pop-up targets. It wasn’t until many studios had passed on that initial design concept that SEGA stepped in and offered to fund Bizarre Creations’ game, provided they dress it up and make it marketable. (It turns out that studio execs prefer mood boards and design keywords to demos with “men made out of cardboard boxes.”)

A group of the wealthy elite have formed an underground club, building courses all over the world, forcing contestants to fight for their lives gladiator-style, and placing bets on the favorites. It’s a silly premise, executed with tongue firmly in cheek (e.g. if you run out of time on a given circuit, your body is blown to smithereens by implanted “micro-explosives”). But compare it to some self-serious military shooter that attempts realism, that tries to imbue its story with moral conflict and drama, and it is refreshing to see a game that feels comfortable just being a game, without any pretensions of being some kind of high art. You are not killing people in defense of a city or to avenge a loved one’s death or to save the world. You’re killing people for points—to increase your combo meter.

The Club never oversteps its bounds by trying to be “an experience.” Almost all of the gameplay elements, the backstories of the player-controlled participants, and The Club itself are hashed out in a brief two-minute introductory cutscene that opens the game; after that it’s basically all action, with loading screens being the only thing between you and another circuit. One neat little coincidence that I thought was a bit ironic is that, once you’ve accepted the conceit of The Club as an organization, the presence of arrows and other path indicators to guide the player actually makes sense. In many linear shooters that feign realism, cars or trees or doors or road banks or whatever will corral you toward your objective. But that’s not realistic at all, right? In The Club, the levels are linear, but within the game’s accepted story framework, they should be!

The basics of the game work like this: you kill someone and are awarded points based on how stylish the kill was (bonus points for headshots, ricochets, long shots, etc.); your combo meter is incremented; if you string kills together quickly, your multiplier increases and your ensuing kills earn even more points. There are several event types—time attacks, run the gauntlets, survival rounds, sprints, maybe one or two others—but at the end of each, your rank against other participants is dictated by your score, not your time. The constant forward motion is required because additional enemies always lie ahead, so it’s a net negative to slow down too much. Playing through the game on Insane difficulty (which is not the highest, by the way), I placed first in a single event out of approximately fifty of them, and I didn’t get too many seconds or thirds.

One intentionally “weak” element of The Club is that the enemy AI is incredibly predictable; they will be in the same place at the same time with very little deviation. This may seem to be a flaw but I think it is actually better than the alternative. Remember that this was originally a shooting gallery. In such a venue, all of the targets are in the same sequence and same location for each runthrough. Small tweaks in performance lead to an incrementally better score; increased familiarity allows accuracy to increase without a reduction in speed, or vice versa. This style of gameplay—perfecting a prescribed course instead of matching wits with a computer—is more fun than an ever-changing environment that would lessen the incentive for improvement. This method of playing the game calls to mind a certain subsection of gamers who perform speedruns, ironing out the fastest possible way to get from the beginning to end of a given level (or even an entire game). Doom was one of the first games to popularize the pastime, while many classic Nintendo games now have their fair share of speedrunners as well. The game I’ve spent the most time with in such a capacity is the delectable Mirror’s Edge, a free-running parkour game in the guise of a first person shooter. But most games do not inspire that type of dedication from me, and The Club isn’t much of an exception. I enjoyed the extent to which I had to refine my routes to simply finish the game on Insane, but I don’t think I will spend time trying to top the artificial leaderboards generated by the game (and the online modes are long dead by now). Had they tied incremental run improvements to progress in the game, I might still be toiling away.

I have very few legitimate complaints. One is that at times the “handling” does not feel as tight as it should. The game features a “quick-turn” action that spins the player 180° but the standard turning via joystick is too slow compared to the responsive aiming controls. Slaloming through the game’s courses, I often found myself hung up trying to move through a doorway and make an immediate turn. I wasn’t concerned with winning any of the tournaments, so it didn’t dampen my enjoyment very much, but such a hiccup would be an infuriating way to have a good run derailed. Another gripe is that the close quarters combat was a little bit hit-or-miss. There was a melee attack but it required very precise aiming which lessened its usefulness considerably, and there were times when my aiming reticle was on an enemy right in front of me but I shot past him, which was annoying. But neither of these issues drag the game down very much; they’re just things you learn to work around.

The Club is simple but hard to pin down due to its unique crossbreed of genres and thus it didn’t really find a permanent home in many gamers’ collections. Matt Cavanagh, the game’s lead designer suggests that the game didn’t sell well because “you can’t put gameplay on the back of a box,” and to a large extent I think that’s true. A few modest tweaks—say, making the violence more cartoonish and over the top instead of “realistic” or giving the player the option to choose their starting loadout—could have helped, but most new things are not immediately accepted and the unique combination of gameplay elements here is no exception. That The Club didn’t spawn a new niche genre is not a knock on the game, but simply a reflection of popular taste.

Sources:

Nouch, James. “The Club retrospective”. Eurogamer. 14 April 2013.