“But the heart beat on, strongly and regularly inside the tortured envelope, and the healing sorceries of oxygen and rest pumped life back into the arteries and veins and recharged the nerves.”

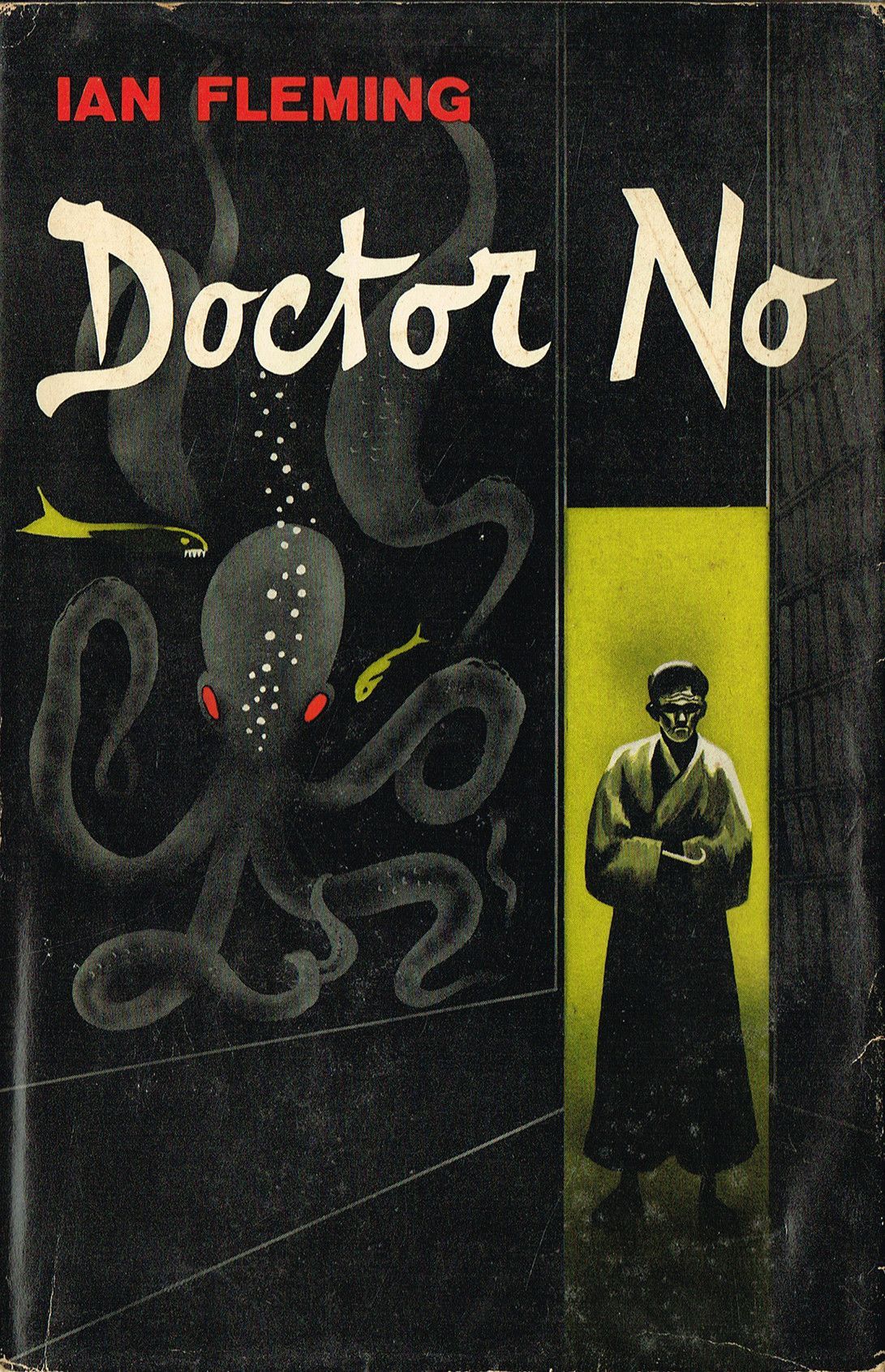

By the sixth James Bond book, it is clear that Ian Fleming is no longer trying to do anything new, but rather to iterate on the successful formula that he finally got mostly right in From Russia with Love: memorable antagonist, alluring vixen, high stakes confrontation, improbable odds, etc. In Dr. No—the first Bond novel ever adapted to the silver screen—the titular fiend checks the box of the iconic villain, but Honeychile Rider and a sadistic deathtrap obstacle course don’t quite offer equivalent merit. But Fleming really had his pacing and plotting down pat, and his writing has transitioned nicely from a drier, physically descriptive style to a more colorful and interesting one, which may even be considered too ornate at times. With the positives and negatives considered, neither will Dr. No serve to convert a detractor nor turn off someone who already likes the character.

After the cliffhanger ending to From Russia with Love, the novel begins with M sending Bond on an “easy” assignment to Jamaica—he will investigate the disappearance of agent John Strangways, who apparently flew the coop with his attractive secretary. Initially, Bond is suspicious of M’s motives for tossing him a softball, but concludes that M wants to test him after his extended time off after being poisoned. Basically everyone except Bond thinks the case will amount to nothing, that he will find the two holed up in a hotel room somewhere. But Bond’s instincts correctly tell him otherwise; in fact, the first chapter of the book details why the prompt Strangways—who first appeared in Bond’s first Jamaican adventure in Live and Let Die—failed to check in for his daily report to London. As he left his friends at their daily card game, buying a round of drinks in recompense for the delay, he passes three blind men tapping their sticks along the sidewalk.

The car key was in Strangways’s hand. Vaguely he registered the moment of silence as the tapping of the white sticks ceased. It was too late.

As Strangways had passed the last man, all three had swivelled. The back two had fanned out a step to have a clear field of fire. Three revolvers, ungainly with their sausage-shaped silencers, whipped out of holsters concealed among the rags. With disciplined precision the three men aimed at different points down Strangways’s spine—one between the shoulders, one in the small of the back, one at the pelvis.

The three heavy coughs were almost one.

Before Bond departs for the mission, M fills him in on a petty issue that Strangways had been looking into, a dispute between the Audubon Society (a real non-profit environmental conservation organization) and the owner of a small island called Crab Key. The owner, the mysterious Doctor Julius No, has set up a guano mining operation—essentially harvesting the poop of a seabird called the Roseate Spoonbill—which was the subject of two society members’ investigation when their plane crashed upon landing at Crab Key.

Once Bond arrives, it’s the usual—a few preemptive attempts on his life, fishing for clues, and meeting his brief love interest. Quarrel, who also appeared in Live and Let Die, returns, whipping Bond back into shape after his extended period of recovery. When Bond finally dares a foray to the island, he meets Honey, a female Tarzan raised in the ruins of her parents’ mansion who has never left Jamaica and is some kind of animal whisperer. Of course, she is a total babe, her crooked nose being the only drawback (in Bond’s eyes). Where Fleming missteps here is that usually the Bond girls are competent in their own right. Honeychile, though, is basically just a feral blonde bombshell who trespasses on private property to collect sea shells and hang out naked on the beach. The island is patrolled by a “dragon,” which turns out to be a gussied up swamp buggy with a flamethrower attached to it. It seems quite silly for such a thing to be included, but I suppose it serves a purpose both as a means by which Quarrel meets his end and later as an espace vehicle for Bond and Honeychile.

When Bond finally concedes and allows himself and Honeychile to be taken prisoner, the peculiar reception creates a superb sense of unease. Henchmen bring them to their eerie resort-like accommodations, windowless and without inside door handles, but otherwise immaculate. They are fed well, receive manicures, and are allowed to bathe. Their attitude almost becomes jovial despite Quarrel having been cripsed only a few hours earlier. But they are also unknowingly given sedatives, and then their host comes to inspect his their drugged bodies, peeling back the bedsheets with his mechanical metal hands.

He keeps them waiting at dinner in a breathtaking underwater aquarium, a large glass dome over which swims various sea-dwelling creatures. As Bond contemplates the feat of construction required to build such a thing he almost begins to admire his captor, who receives a memorable introduction.

What an amazing man this must be who had thought of this fantastically beautiful conception, and what an extraordinary engineering feat to have carried it out! How had he done it? There could only be one way. He must have built the glass wall deep inside the cliff and then delicately removed layer after layer of the outside rock until the divers could prise off the last skin of coral. But how thick was the glass? Who had rolled it for him? How had he got it to the island? How many divers had he used? How much, God in heaven, could it have cost?

“One million dollars.”

It was a cavernous, echoing voice, with a trace of American accent.

Bond turned slowly, almost reluctantly, away from the window.

Doctor No had come through a door behind his desk. He stood looking at them benignly, with a thin smile on his lips.

Dr. No proceeds to try to justify himself to Bond, explaining that the power over another, to the extent of life and death, can only truly be achieved in a private enterprise such as his—not by a government official who must answer to his citizens. It seems like Fleming maybe wanted to get a bit philosophical, discussing the notion that all power is merely illusion, but what it amounts to is simply some nice flavor in the midst of a spy thriller, which is fine. Soon, Bond finds himself forced through a gamut of physical challenges, designed by the insane doctor to test the limits of the human will to survive, which ends in Bond facing off with a giant squid. (It turns out that Honeychile was subjected to a swarm of crabs which do not harm her because she lies absolutely still.) Bond kills Dr. No by hijacking a guano distribution machine and channeling its flow to bury him and then Bond and Honey ride off into the sunset aboard the dragon buggy.

Certain elements, such as the delightfully caricatured Dr. No, his fabulous lair, the oddly in depth descriptions of guano mining and the history of its economic value, the quaint self-censorship (“May be a —ing crocodile!”), give the book a leg up. I was also happy to see Fleming again toying with morality and the psychology of evil people. He makes the case (using Dr. No as a mouthpiece) that all great scientists, philosophers, and religious leaders are maniacal. Later, having rained down literal tons of bird poop on the dastardly, claw-handed evil genius, Bond ponders the eternal fate of the soul.

And where had Doctor No’s soul gone to? Had it been a bad soul or just a mad one? Bond thought of the burned twist down in the swamp that had been Quarrel. He remembered the soft ways of the big body, the innocence in the grey, horizon-seeking eyes, the simple lusts and desires, the reverence for superstitions and instincts, the childish faults, the loyalty and even love that Quarrel had given him—the warmth, there was only one word for it, of the man. Surely he hadn’t gone to the same place as Doctor No. Whatever happened to dead people, there was surely one place for the warm and another for the cold. And which, when the time came, would he, Bond, go to?

Lest some bemoan the fact that I have not yet mentioned the author’s unsubtle racist tendencies for the umpteenth time, yes, they are present yet again. Dr. No and his goons are all Chinese and all evil and the Jamaicans are spoken of condescendingly, among other things (though note that Fleming summered in Jamaica and writes about it with obvious adoration).

Dr. No is an uneven novel, offering some hitherto unseen elements but lacking depth in several other key areas. So while it has some delectable high points, taken as a whole it ranks somewhere in the middle of the pack of Fleming’s series.