“When a man’s got money in his pocket he begins to appreciate peace.”

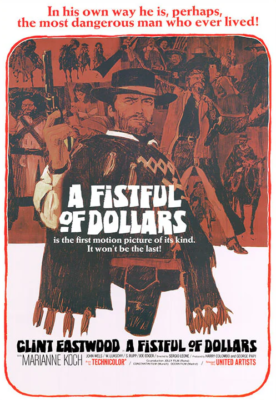

With A Fistful of Dollars, Sergio Leone began to reinvigorate and reshape the Western, bringing to bear a gritty, operatic intensity and exciting film style on a genre that had been all but abandoned by feature directors and then tamed and domesticated by television. Leone’s approach relied on sweaty close-ups, panoramas, dynamic choreography, and archetypal scenarios, as well as a brilliant score of whistles, chants, and whipcracks from Ennio Morricone and Clint Eastwood’s now-iconic visage—eyes squinting out from a bearded face peaking from dusty poncho, gnawing a cigar—much more so than a robust, original story. In fact, the story (and even the dialogue and visual compositions!) was so derivative of Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo that the Japanese filmmaker successfully sued for a percentage of the film’s gross—which seems like a good deal for two novice filmmakers who had stepped on the toes of a legend.

At least for me, Leone’s reimagining of the samurai tale, now featuring an enigmatic gunslinger blown by the wind into a bleached-out, tumbleweed border town imbued with an air of mythic desolation, in combination with his unique rhythms and visual dynamism, make it hard to declare Kurosawa’s film the clearly superior picture. I’d honestly call it a toss-up, though maybe that’s because I would generally give an edge to Westerns over samurai films. I think Kurosawa’s film features a more full-bodied and dramatically viable narrative, but Leone’s extreme style appeals to me more, even at this nascent stage. Even the comic book styled title sequence does it for me. (Both films are superior to Walter Hill’s remake, Last Man Standing.)

Leone, who had only solo-directed one film prior to this one, (The Colossus of Rhodes, though he reportedly carried much of the load on The Last Days of Pompeii, officially credited to Mario Bonnard), brings a bare-bones but distinct artistic vision to this low-budget film, noteworthy and properly extolled in many regards by critics and general audiences alike, that he would further work out across two more films with Eastwood (For a Few Dollars More, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly), which would gradually amplify and refine the original’s best qualities and would all be packaged as a trilogy as the last one was rolled out in the United States in 1967.

If it didn’t usher in the spaghetti Western, it certainly brought an iconographic, violent, amoral sensibility to the genre and to America, where films like Bonnie and Clyde and The Wild Bunch would soon follow in its footsteps and change the landscape of cinema forever. And if it is the least of Leone’s Westerns, well, that just means we have more great films to savor. A final, staggering thought: this was Clint Eastwood’s first starring role. He was older than I am now when the film was made in 1964, and the dude is still making films. In fact, his latest, Juror #2, just finished its theatrical run.