“Who’s praying? I don’t need any prayers.”

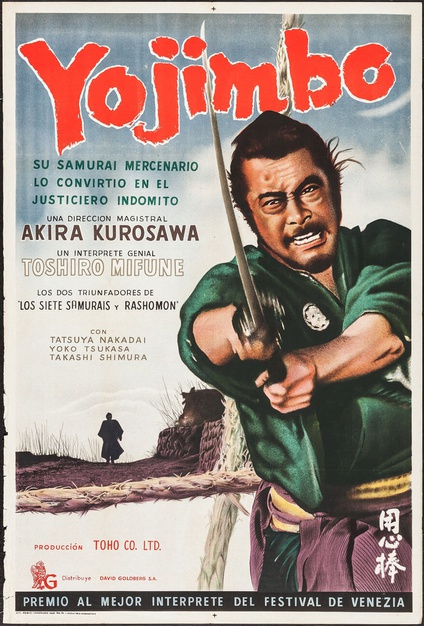

Kurosawa never directed a film in the United States and yet early Hollywood films influenced his career almost as much as his works served as a touchstones for the future of American cinema. By the time Yojimbo was released, Kurosawa was well known, having directed a string of classics in the 1950s. Decidedly less ambitious than the likes of Rashomon or The Seven Samurai, Kurosawa’s small-scale samurai film finds the director at the top of his game, working with long-time collaborator Toshiro Mifune, likewise at the height of his powers.

The film informs us via on-screen text that at the end of the Tokugawa Dynasty many samurai were left wandering around the countryside in search of employment. A popular setting for samurai films, the Tokugawa era was one of relative peace, during which many samurai chose to become rōnin—masterless samurai free to follow their own consciences rather than the wishes of their masters.

We begin as our protagonist, Sanjuro (Toshiro Mifune), finds himself at a literal crossroads, flinging a stick into the air to determine the direction he will travel. His wandering brings him to a small town where he encounters a young man arguing with his father over his life’s dull prospects, wishing to join a gang and chase a short life of excitement. As he strolls down the town’s wide, abandoned street, second-story windows open and curious faces look down at him. He sees a stray dog trotting along the road with a severed human hand clamped in its jaws, a grim indicator of the hostile environment he has entered.

He is soon drawn into a situation where no clear line exists between good and evil. There are two merchants: Tokuemon (Takashi Shimura), a dealer of saké, and Tazaemon (Kamatari Fujiwara), a dealer of silk. Once partners, the two had a falling out and are now at war, turning the town into a corrupted wasteland. The film centers around this dispute, viewing the breakdown of society, neighborly conflict, and the effects of greed through a satirical lens.

Kurosawa challenges the viewer with a morally unclear plot and a dearth of truly good characters. Even Sanjuro proves to be morally questionable. Upon entering the town, he has no money, and sees an opportunity to both profit and exercise his talents in the impending conflict. His motives seem aimless, and his commitment to amorality is so distinguished that it is surprising when he rescues a kidnapped family. The farmer, his wife, and their son that Sanjuro saves are the only characters worth redeeming in the town, but the rōnin gives no explanation for his decision to jeopardize himself by setting them free.

Throughout the film, he acts much more as puppet master than subservient agent, and although he ostensibly hires himself out to both sides of the conflict (cleverly subverting the expectations of a loyal samurai), he remains above the materialistic dispute. But as he subtly manipulates the petty gangsters to destroy each other and cleanse the town of evil, he is arguably on equal ground with them, morally—his intelligence and swordsmanship are what set him apart.

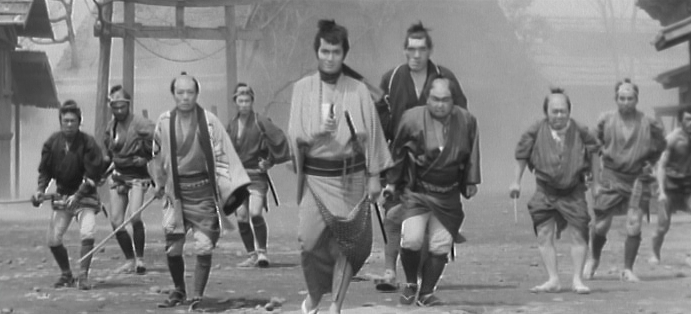

Indeed, much of the film’s allure stems from Sanjuro’s flippant disregard for the pettiness surrounding him and his cerebral ability to influence the tides of the conflict while enacting minimal violence of his own. As the gangsters posture meaninglessly, attempting to intimidate Sanjuro with their tattoos and braggadocio, they all flinch noticeably as the wandering rōnin removes his hand from his kimono to adjust the piece of straw in his mouth. He tells the gangsters they are cute and to provokes them into attacking him, confident even in a one-against-many skirmish. After the confrontation, he calmly strolls through the town square and suggests to the speechless cooper that he will need “two coffins; no, maybe three.”

By aligning the audience with Sanjuro, we are asked to view the conflict as he does. After provoking the two sides into a battle, he climbs to the top of a small perch and calmly watches the fight below. Even if we are not to provoke conflict, we are encouraged to look down at the madness unfolding before us, to live above the absurd, self-destructive tendencies of human nature.

Many of Kurosawa’s films toy with the idea that the world is irredeemable. Sanjuro’s detachment from the ruthlessly capitalist impulses of the merchant town, and his advice to the young man he leaves alive in the final battle—“Go home,” he tells the boy, “a long life of eating porridge is best”—may seem counterintuitive. He is a wandering ronin, after all; one who just broken the contracts he had made. Who is he to give advice? But who better to give advice than one who is supremely capable of committing the violence these men think they crave? Perhaps that was Kurosawa’s subliminal message to the youth who paid to see a violent movie. (The interaction with the boy is echoed more than forty years later as The Bride in Kill Bill Vol. 1 spanks a child with her sword, and tells him to go home to his mother.)

Sanjuro appears to be nearly invincible as the townspeople are in awe of his abilities, but the introduction of a revolver turns the whole situation on its head. His earlier act of compassion comes back to bite him, as a note of thanks is discovered by Unosuke (Tatsuya Nakadai)—the wielder of the firearm—who strips Sanjuro of his sword and has him beaten.

His wit allows him to escape, and he recovers in hiding. Led by Unosuke, the unruly gang lures Sanjuro back into the fray by stringing up the restaurant owner who has kept him fed and sheltered throughout the film. Finally, Sanjuro unleashes a masterful display of swordsmanship, leaving the caricatured gangsters bleeding out in the streets. He smoothly slices his way through their ranks, takes down the shooting hand of Unosuke with a throwing knife. As the gunslinger slowly dies, a pool of blood spills out from beneath him, one of several instances of rampant bloodshed. Released in 1961, Yojimbo predates the films usually cited as the culprits for the origination of violent cinema—notably Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and The Wild Bunch (1969)—though its black-and-white stock might have something to do with that.

Toshiro Mifune is self-possessed as the rōnin Sanjuro. His bravura is evident in his calm and collected dialogue, his characterization infused with nervous shrugs, crossed arms beneath his kimono, and an aura of wisdom during the calamitous dispute. Kurosawa edited the film himself, as he did with many of his own releases. Typical of his oeuvre, the shots are well-planned (credit is due to cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa), the cuts are well-placed, and the editing is nearly invisible, though the screen wipes as scene transitions haven’t aged well.

Yojimbo was created as a feature-length homage to the American Western—the dusty, square streets; the lonesome and anonymous pilgrim; the cutthroat rivals. Harmoniously, Yojimbo in turn sparked Sergio Leone to create A Fistful of Dollars, launching the career of Clint Eastwood and the genre of the Spaghetti Western, unleashing a slew of future projects into the cinematic landscape. With its ties to cinema both past and future, as well as its East-West crossover sensibilities, the film is a unique example of the interconnectedness of the artform, and the global intermingling of cinematic inspirations. While not Kurosawa’s peak as an artist, it is certainly one of his best efforts at balancing masterful artistry and entertainment value. Merging intense action, an iconic performance from Mifune, and social commentary, Yojimbo is an enduring classic that remains one of the rare breed of film that is simultaneously suited for the masses and aficionados alike.