“Nothing’s sacred anymore.”

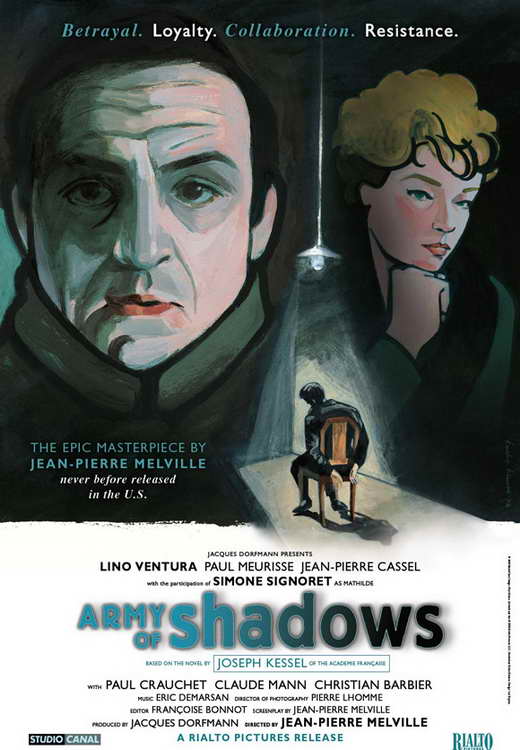

Jean-Pierre Melville’s Army of Shadows (L’armée des ombres) is a bleak affair. It offers a view of the French Resistance during the Nazi occupation of France. It is related to the war, but it is not about it. Instead, it is about the fighters’ steely sense of duty while living in an atmosphere of pervasive dread. We don’t see fantastic explosions or theatrical heroics. Instead we see brutal, desperate, and necessary decisions that these men and women are forced to make knowing they will likely die without seeing the fruit of their actions.

In Melville’s previous film, Le Samouraï, the protagonist dutifully carries out his tasks, stoically marching toward his inevitable end, almost as if the narrative is designed to mourn for the character as we watch his demise. Our protagonist here, Resistance commander Philippe Grebier (Lino Ventura), is similarly pensive. He speaks little, and seems to accept his fate as it comes over the course of the film’s runtime; the sparse dialogue and dearth of humor paints a stark image of the war, and the heavy burdens that were carried.

The Vichy government officially allowed the Nazi occupation of France in order to receive immunity from the German military. We are never given a top-down view of the Resistance in Army of Shadows, instead we follow a group of frontline operatives as they utilize guerilla tactics to achieve their aims. They use aliases, live double lives, form deep bonds of trust amongst themselves, and risk their lives repeatedly as they negotiate murky circumstances regularly.

An early scene exemplifies the ambiguous situations that our protagonists regularly encounter. After escaping from captivity, Grebier ducks into the nearest open door he can find, belonging to a barber shop. In a tense scene, the barber gives Grebier a shave, without questioning why he had barged in so late at night and is breathing so heavily; without much talking at all, in fact. Upon realizing that he had entered a barber shop, Grebier has to act as if he intended to be there, and so he must expose himself to the blade of a man of unknown loyalty. After the shave is complete, Grebier wipes the remaining lather from his face, and tries to leave hurriedly. He hands the barber a wad of bills; the barber tells him he will get his change, and walks off screen. As Grebier tries to quickly put on his coat and make his way back outside, the barber reappears with his change and a coat of a different color, offering it to Grebier so that he may escape further attention in the streets. The threat now past, and the barber’s allegiance shown, Grebier nods in unspoken gratitude toward the man who moments before had been a potential enemy.

Melville understands that action can deflate the sense of suspense. The real battles we see are fought within the minds of the Resistance members, as they are thrust into futile situations and must set aside their moral qualms for the sake of the greater good, which they know they will likely not live to see. They live in a state of unease, unsure of where the next threat will materialize or when they will be called upon to commit an act they would deem heinous in a neutral context. Melville could have decided to add any number of action sequences into the film, yet he shows restraint; rather than bursts of theatricality, we get a steady smolder.

Grebier and two of his associates must execute a traitor of the Resistance. One of them poses as a policeman and tricks the young man into coming with him. Here we may expect gratuitous violence, but not in the hands of Melville. They take the traitor to a rented house, where they plan to execute him. Upon arriving they realize that neighbors have moved in next door, and so they cannot use a gun for fear that they neighbors will hear it; further, no one has a knife with them. Grebier does not want to delay the execution, so despite protests, he orders his men to strangle the traitor with a towel. Lepercq (Paul Crauchet), eyes vacant, carries out the deed.

Dressed in German uniforms, three maquis members attempt to rescue fellow agent from the Gestapo, using forged papers that give orders for his transport. He had been snatched off the street, imprisoned, and tortured. Here is where a lesser film would introduce a dramatic jailbreak, but instead, when the doctor notifies the fraudulent medical crew that their patient is unfit for transport, they get back in their vehicle and depart. They do not attempt anything rash; they cut their losses—even though that loss is the life of their friend—and begin formulating their next plans. In both of these scenes, little action occurs, but that which does evokes a very strong emotional response. Instead of physical theatrics, the focus becomes the intellect; the mindset of one who must make such ruthless decisions.

Although Melville was himself one of some six hundred Resistance members, the account is not historically accurate. It is more of a haunted meditation than a historical portrayal. In service of this, it appears that Melville is primarily concerned with aesthetics and mood, and plot only secondarily, though I am not sure if this emanates from the director’s auteurist tendencies or the especially personal material he is dealing with here. In crafting a story where we are prompted to begin mourning the demise of all of the protagonists from the beginning, I am ultimately indifferent about which characters are put through which dire situations. And perhaps that is the point: that the Resistance itself is more important than any single constituent.

The film is very effective at manipulating the viewer into that line of thought, exemplified by the relationship between two brothers, and Grebier’s initial escape from captivity. The brothers—Luc (Paul Meurisse) and Jean-François Jardie (Jean-Pierre Cassel)—are both members of the Resistance and yet never know that the other is as well. Jean-François, a former fighter pilot, visits his older brother after completing a smuggling mission in Paris. Luc, a renowned philosopher, seems to live a comfortable life removed from the situation. They share a meal but do not say much out loud; instead, we hear the thoughts of the younger brother in a voiceover, questioning whether he shares more with his fellow Resistance members than with his own brother. Later in the film, we leave Jean-François in dire condition, imprisoned under an alias, contemplating if he should take his cyanide capsule or let his cellmate use it to escape his own torment. In order to avoid jeopardizing the movement unnecessarily, many powerful figures within the Resistance remain anonymous. It isn’t until we are well into the film that we learn that Luc Jardie is their leader, orchestrating from within the shroud of the deepest of shadows. He had intentionally acted aloof during their visit for fear that his brother would betray him if he knew of his true status.

In an early scene, Grebier is taken in for questioning by the Gestapo. While awaiting his interrogation, he convinces a fellow Resistance member to take part in his escape plan. The man follows his instructions; as Grebier feigns to ask a question of a guard before quickly pulling the guard’s own knife and stabbing him with it, the young man runs through the front door of the building. This draws attention and several guns begin chattering at him as he tries to dodge their fire. This diversion allows Grebier to escape to the barber shop. Grebier, a commander, was more important than the young man that he sent to his death, and because of that he was required to harden his heart, numb his conscience and willfully send a young man to his death to preserve himself.

Aesthetically, the film looks bleak yet beautiful. Blanched environments filled with extras (especially the opening scene in the prison camp), characters concealing themselves behind the upturned collars of their trench coats, and stylized yet sedate action sequences give the viewer a glimpse of the Resistance through a lens jaded by having lived it.

Mathilde (Simone Signoret) is the only female Resistance member with which we spend significant time. However, she has been stripped of nearly all female traits and is simply a fighter; in fact, our only glimpses of femininity in the film are when she briefly dresses promiscuously in a montage of different disguises she utilizes, and when she comes close to tears at her failure to save her fellow maquis member from prison. During Gerbier’s various absences due to imprisonment and hiding, Mathilde had carried on steadfastly in his place, and is considered perhaps the most crucial member of their guerilla band. Late in the film, she is captured. In the film’s penultimate scene, while in hiding, Grebier and his associates argue over his order for her to be executed. The first response to Gerbier’s order is a straight refusal, followed by a threat to Gerbier if he tries to carry it out himself. Then, Luc Jardie materializes from the shadows of the safehouse, explaining why it must be done, and that it is in fact what Mathilde desperately wants. After the orders are accepted and the associates departed, Jardie confides to Gerbier that his postulations on the mental state of Mathilde are only theoretical, and he is unsure if he has read the situation correctly. He determines that she deserves to see him, their leader, before they die, and so in the closing scene he is present as their most exemplary representative is coldly eliminated; a fate which they all would eventually meet.

Enjoyable post. I tend to be of the same mind with most of what you wrote.

I admire the useful information you offer in your blog posts. I will bookmark your blog and have my youngsters come here often. I’m quite sure they will discover a lot of new things here!