“Nothing like a little disaster for sorting things out.”

Like the disappearance of Anna in L’Avventura, the inciting event of Blow-Up is almost incidental to film’s aimless plot; a little tease that tricks the viewer into thinking that a substantial narrative might be taking shape when, in fact, one is not. This is intentional, of course. It’s Antonioni’s schtick—a critique/appreciation of a bored culture couched inside of a narratively boring film, albeit a narratively boring film bolstered by lush visuals and a pleasant Swinging London backdrop that includes a troupe of mimes, antiwar protests, a Herbie Hancock score, and a performance by the Yardbirds (featuring both Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page).

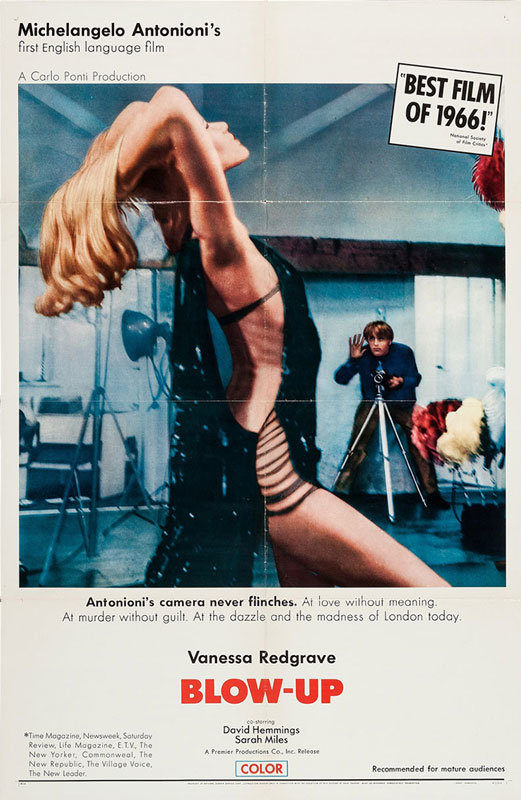

After more than half a movie’s worth of slice-of-life longueurs involving emaciated fashion models posing in gaudy outfits, visits to antique shops, and a sneaky candid photoshoot in the park, a libertine fashion photographer (David Eddings) has a moment of insight that threatens to shake up his jaded world. He’s already spent a good deal of time fruitlessly interrogating the enlarged photographs from the park—his curiosity piqued by his unwitting subject’s (Vanessa Redgrave) startled reaction upon noticing him—when he comes to suspect that his very presence in the park that day may have prevented a murder. Briefly distracted from his investigation by an orgy with a couple of nubile potential clients, he springs forth from his post-coital rumination with the startling realization that the murder actually occurred and that he captured it on film. Or did it, and did he? Was it all an illusion? Is all of life an illusion?

Antonioni is certainly not making a mystery thriller in the strictest sense. Not only is the mystery not solved, but we learn very little about any of it at all. The victim, the perpetrator, the accomplice, and even the anti-hero remain ultimately inscrutable, almost as if we should have only been vaguely interested in them in the first place. Which is entirely the point. As he tries to follow up on his hunch, the photographer is continuously sidetracked by the existentially uncertain culture that surrounds him to such a degree that the coda finds him fetching a fake tennis ball for a company of mimes who eagerly desire his participation in their charade. If he believes the ball is real, then it’s real. If he believes Jeff Beck’s guitar is worthless, then it’s worthless. If he believes he witnessed a murder, then he witnessed a murder. In this world, there is no objective reality, no certainty, no meaning, no truth. Nothing really exists, and yet we must act like something does, because we exist—don’t we? From this perspective, our protagonist’s apathy makes complete sense. Consider the film’s tagline: “Love without meaning. Murder without guilt.”

Though it served as a major plot inspiration for two incredible thrillers (Coppola’s The Conversation and De Palma’s Blow Out), and helped bring down the Hays code, Blow-Up is emphatically unlike those Hollywood films. Its primary aim is not entertainment, but a philosophical comment—on cultural decay, spiritual malaise, the nature of reality, the temporality of the world, the meaning of art, the human propensity for constructing stories from images, voyeurism, and so on, but most central is the idea that we have no mechanism to authenticate our experiences. We can’t know what, if anything, is real. It’s a film tailor-made for film school dissection, and in that sense it largely succeeds as it quite effectively generates discussion about the underlying ideology reflected in its form, style, and narrative. One need not adhere to the belief that life is guided by chance and totally meaningless to proclaim that Blow-Up is a brilliant artistic depiction of that notion.