“I guess nostalgia ain’t what it used to be.”

There’s a lot of interesting things going on in Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull’s History Lesson, another one of those gloriously messy Robert Altman films that seeks to foster a rich dialectic between reality and fiction by examining a popular genre. Rather unfortunately, it has precious little to say about its primary theme. But, if we are willing to spend some time pondering and studying, it eventually reveals an inspired meta-theme that is explored much more subtly and fruitfully through the director’s unconventional style.

Previous Altman films such as McCabe & Mrs. Miller and The Long Goodbye took well-established genres and gave them authentic textures by filming on location, employing talkative ensemble casts, and using improvised techniques of sound and image, usually resulting in pleasantly organic and free flowing pieces that work on multiple levels. Buffalo Bill does much the same, but, in a sort of reversal, it takes a historically authentic enterprise—Buffalo Bill’s Wild West—and uses it to challenge the myth of American heroism by positing that the production was primarily a clever invention of show business; a sanitized mythologizing of unsavory historical events.

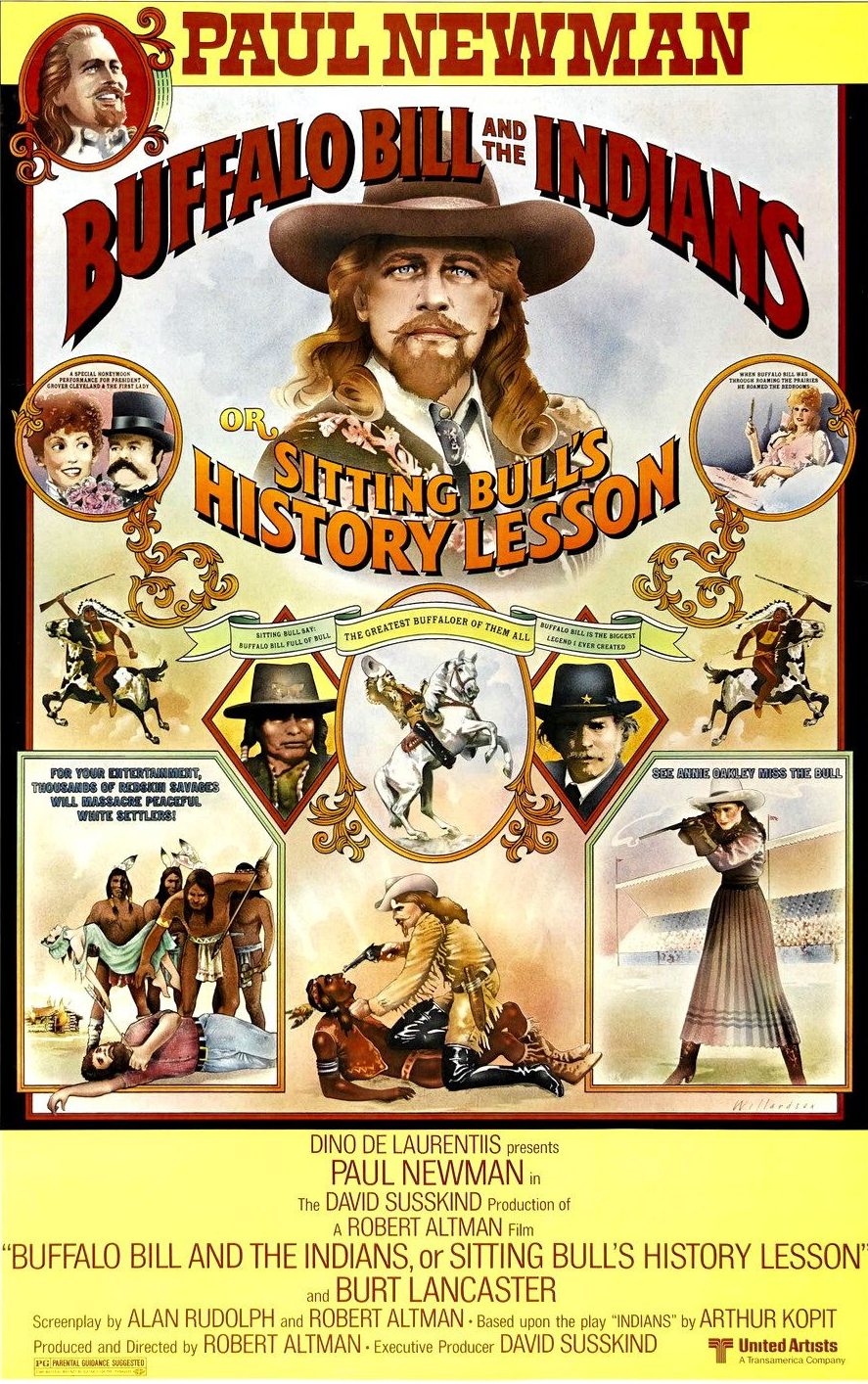

Set within the compound of the Wild West revue, wherein history was rewritten, recontextualized, and reshaped into revisionist family entertainment, the film centers on the iconic Buffalo Bill (Paul Newman) himself. Altman’s depiction of the character is not the pioneering entrepreneur of popular perception, but rather, a hot-tempered, shallow prima donna haunted by the knowledge of his own inauthenticity. Indeed, nearly everything about him reeks of fraud, from his flowing hair piece, to his manipulated marksmanship, to his lousy horseback riding. Under no circumstances could one envision the character in this film prevailing in the battles he playacts in front of crowds. And yet, the man’s ego is painfully entwined with his own legend; so much so that any reminder of his lifelong charade torments him. To wit, he cannot bring himself to speak to Ned Buntline (Burt Lancaster), his myth-making biographer who claims to have invented the character of Buffalo Bill. Neither can he bear the stoic presence of Sitting Bull (Frank Kaquitts), an aging Indian chief whom he plans to exploit in his show, but who wins every negotiation by simply not playing the game. Indeed, the effect of Sitting Bull’s inclusion in the show is exactly the opposite of Bill’s intention, as the nasty audience eventually recognizes this diminished old chief as a bona fide mythical figure.

The film’s acid point, that America’s self-image largely consists of wild exaggerations and outsized fabrications, is established quite early on and then circled endlessly. It grows tiresome, but finally comes to an unexpectedly effective double climax in which Bill frantically rants at the specter of the departed Sitting Bull, his identity as the savior of the frontier finally disintegrating in his own mind; and then symbolically slays his stand-in at the next show, standing over his “scalped” foe in false triumph with a hollow smile pasted on his face.

But if we cannot find a strong foothold in the film’s didactic character deconstruction, there is plenty here for Altman disciples, particularly as regards his “broad canvas” approach to directing. The enormous set, period costumes, and authentic props all appear entirely genuine. The showgrounds are decorated with gaudy banners and painted likenesses, and real rodeo professionals pepper the background. The ensemble cast is magnificent if underutilized and includes Geraldine Chaplin, Kevin McCarthy, Joel Grey, Harvey Keitel, Will Sampson, John Considine, Shelley Duval, Pat McCormick, and Denver Pyle, among many others. As is typical for Altman, all of them are miked and many cameras roll at once, roaming and zooming, creating that special sense that for a few months the film set was a gigantic roleplaying game where everyone remained in character for hours at a time. There are puppet theaters, comedic sideshow acts, constant sounds of gunfire, and so on and so forth. It’s a lively place.

This allows for some amusing self-reflexivity, wherein Altman uses his overlapping mini-narratives and crowded soundscape to tease whether certain elements are “part of the show” or part of the movie. One of the neatest tricks is that the house band performs all of the music for the film—well, all of it except the operatic ululations of Bill’s three paramours and a subdued performance when President Cleveland comes to take in a show.

Moreover, from amongst peaks and valleys of the main narrative arises a commentary undergirded by the filmmaker’s unique approach: using sound and image in complex ways, often in intentional conflict, Altman crafts a self-conscious film that examines its own criticisms from within, situating the audience in a slippery space between reality and illusion.

Consider the opening credits sequence, in which a cowboys-vs.-Indians showdown is gradually revealed to be artificial. Narration and music, which by convention initially seem non-diegetic, respectively outline the premise and bolster the action, but then another voice yells, “Cease action!” We then realize that the entire opening sequence was merely a rehearsal; that it wasn’t real at all. Dead men stand up and a building is carted to a new location by horses. The band starts up another piece. But—of course it was real. Altman had his whole cast and crew out there on a sprawling set, didn’t he? This is underscored by the fact that one of the performers was actually injured during the rehearsal. That is to say, the movie character was injured; the film actor was not. This line is crossed again later when Annie Oakley accidentally shoots her husband during a performance and he pretends like it was part of the act. We are left grasping until Altman cuts to Buntline reciting Buffalo Bill’s origins as he sits in the bar, though this new reality is also quickly undercut by a nameless old soldier (Humphrey Gratz) who offers a different story.

In this way, Altman develops a commentary that’s more layered than the surface level criticisms of America’s rewritten history books. It raises questions about history- and legend-making as a general practice, and takes a more pointed approach toward celebrity and filmmaking in particular by considering Newman’s own status as an icon of cinema. At one point, Bill criticizes Sitting Bull because he doesn’t want to change with the times, and yet, what is the purpose of Bill’s entire enterprise if not to preserve a single moment in time, fabricated or not? Further, what is the film doing if not immortalizing the star of Paul Newman (even though it doesn’t treat him with the same reverence that other New Hollywood vehicles did)?

Altman had moved toward films without conventional characters and arcs, that were instead propelled by internal momentum found and polished in the editing room. Buffalo Bill is perhaps the closest he came to capturing the ideal outcome of this approach, as almost every moment is suffused with a sense of real-time revision, as the characters are constantly and consciously reforming their self-images and the film itself is deliberately elusive with its own internal realities. It’s as if Buffalo Bill is a swirling vortex around which everything—performers, props, guests—must remain in constant flux to prop up the fiction. Anything and anyone is liable to be tossed out or reworked should the need arise.

Consider the scene in which Sitting Bull and his entourage briefly leave their lodgings for a ceremonial walk. The fact of his “escape” is immediately absorbed into the lore of the show, and Bill gears up to ride out after him, galvanized by an opportunity to live out the fantasies he’s rehearsed for years. He’s already envisioning ads for the show indicating that he had to drag the savage Indian back to the revue. The band begins playing as the film shifts into the form of a classical Western, only to be undercut when Bill returns to cheers and heraldic music empty-handed. It’s in these reflective moments, bluntly rendered as Newman gazes at himself in the mirror, that we are asked to question the myth-making apparatus of popular entertainment. He eventually realizes that the one person he needs to explain himself to is Sitting Bull, even as his entire show is predicated on the fact that the shriveled old man is his mortal enemy.

Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull’s History Lesson is a shaggy and occasionally frustrating film. Its freeform narrative, which spends as much time reveling in the revue’s margins as critically examining its star, is eerily touching at points and makes for a wonderful backdrop against which Altman is able to craft a superlative self-reflexive Western. Its surface level offering lacks the appeal of a Peckinpah revisionist piece, and it doesn’t quite stack up against Altman’s earlier foray into the genre. However, taken as a whole—as an object of cinematic study, a comment on the artifice of performance, and a myth-making device in itself—it is a fascinating piece of American art.